“No Offense, But” is back for the final podcast of the year. Join outgoing Opinion editor Keshav Tadimeti, outgoing assistant Opinion editor Ani Gasparyan and columnist Enming Zhang talk about UCLA’s plan to reduce enrollment rates and grow summer classes. After the break, they bring out the tissue boxes for administrators’ lack of transparency and the editors’ final shoutout before they graduate.

Ryan Kreidler, Leading Off Two Years Later

In April 2017, Daily Bruin Sports Video spoke with shortstop Ryan Kreidler about adjusting to life in college baseball in the first feature video of series “Leading Off.” Two years later, the team caught up with the Detroit Tigers’ No. 112 MLB draft pick for 2019 to see how things have changed since his freshman year.

Daily Bruin Senior Class Reflects on Office Life -30-

This post was updated June 9 at 9:19 p.m.

Each year, graduating Daily Bruin staff members can write a -30- column to summarize their experiences here at The Bruin. This year, some also elected to be interviewed for this video, in which they further reflect on the time they’ve spent in the office.

Ted Lieu, survivors of conversion therapy discuss banning practice at roundtable

Congressman Ted Lieu said he thinks conversion therapy needs to be banned at the federal level at a UCLA event Thursday.

The UCLA School of Law hosted a roundtable discussion with survivors of conversion therapy during Pride Month to discuss the Therapeutic Fraud Prevention Act, or H.R.2119. This legislation, which was first proposed by Lieu in 2015, would allow the Federal Trade Commission to recognize for-profit conversion therapy as a fraudulent practice and create a precedent for banning conversion therapy nationally.

Conversion therapy is the practice of attempting to change an individual’s sexual orientation or gender identity through medical practitioners, licensed professionals and religious influences.

Lieu said he finds for-profit conversion therapy practitioners to be dangerous and disingenuous, and he seeks a nationwide ban to supersede slower state-by-state legislation to ban this treatment.

Lieu sponsored a bill to ban conversion therapy practices on minors in 2012 when he was a state senator, which then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law. California was the first state to successfully ban conversion therapy as a result of Lieu’s bill. In total 18 states ban the practice on minors.

Aidan Arasasingham, a second-year global studies student and director of legislative affairs at the Undergraduate Students Association Council, said he thinks although it’s great California set the precedent in 2012, more work still needs to be done.

“Because young people are disproportionately affected, it warrants federal action to protect these students and individuals,” Arasasingham said.

Jocelyn Samuels, executive director of the Williams Institute, which conducts research on LGBTQ issues and public policy, said conversion therapy has been discredited by every major medical association, including the American Medical Association, American Psychological Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics for being ineffective and harmful.

The Williams Institute released a report in 2018 that estimates 698,000 LGBTQ individuals have undergone conversion therapy in the United States, with approximately 350,000 receiving this treatment as adolescents.

The panel of speakers at Thursday’s event included survivors of conversion therapy who shared their experiences. Mathew Shurka, co-founder of the National Center for Lesbian Rights campaign “Born Perfect: Ending Conversion Therapy,” said his family paid over $35,000 over the course of five years for him to receive the conversion therapy. For three years, he received conversion therapy in Los Angeles.

Kate McCobb, a survivor of conversion therapy, said her therapist attributed her sexual orientation to being a result of childhood abuse, and she became convinced that she was sexually assaulted, even though she never was.

James Guay, another survivor of conversion therapy and a licensed therapist, said a common method in conversion therapy is to find a root cause of their sexual orientation by directing the patient toward realizing any underlying traumas.

“One of the harms (in conversion therapy) is developing false memory syndrome, where they believe something happened to them and they feel the trauma, even if it never occurred,” Guay said.

Some survivors of conversion therapy may also develop harmful symptoms as a result of their experiences, Guay added.

“The shame and rejection of self … leads to problems like anxiety, depression, addiction and suicidal ideation,” he said.

The Trevor Project, which is the largest suicide prevention organization in the U.S. for LGBTQ individuals, found that LGBTQ people who come from a highly rejecting family are eight times more likely to attempt suicide than individuals from an accepting family, said Casey Pick, senior fellow for advocacy and government affairs of The Trevor Project.

“Some of these LGBT youth reach out because their parents are actively threatening to send them to conversion therapy,” Pick said. “Others call us because they’ve tried conversion therapy, it is not working, and feelings of isolation and failure contribute to suicidal thoughts.”

Pick added that others who reach out to The Trevor Project’s landlines or text message support channels are doing so because they’re desperate to escape what seems like torture, or they know someone who has died by suicide as a result of undergoing conversion therapy.

In 2017 it was found over 40% of homeless youth are LGBT, with 46% stating family rejection as a factor behind homelessness, according to a Williams Institute study.

Lieu introduced H.R.2119 in the House of Representatives twice before, in 2015 and 2017. Although it failed then, he said he feels confident it will pass through the House of Representatives now given the new Democratic leadership and majority elected after the 2018 midterm elections.

Jenna Bushnell, communications director for Lieu, said the congressman hopes to elevate the voices of those who have undergone conversion therapy.

“Pride Month isn’t just about celebration, it’s a time we want to highlight fixing these injustices,” Bushnell said.

The newsroom provided me with a sense of belonging away from home -30-

This is so hard to write. Seriously, I’ve started five drafts already, only to stop midway each time. Nothing I write seems complete, almost as if I’m doing an injustice to my college experience because I can’t possibly sum up the best four years of my life in one column.

I applied to UCLA on a whim. So much of a whim that I didn’t even tell my own mother I was applying. In hindsight, that was probably not the smartest choice, but I convinced myself I had set an unattainable goal, and prepared for another four years on the East Coast. But then, it happened. I got in.

That marked the start of the longest summer of my life. My weeks were spent daydreaming about UCLA and marking down the days until I could feel the Los Angeles sun on my skin. I committed blindly without seeing the campus, as I told myself pictures on Google Images would suffice. I packed my bags, said my goodbyes and headed off to start my new adventure.

Little did I know, though, that college is hard. I mean, it’s extremely hard. I felt lost and confused by how the place that was full of forging lifelong friendships and making new memories somehow managed to make me feel so alone at the same time. My first few weeks were plagued with homesickness and culture shock, as I tried my best to make a home for myself in a place that was so far from it.

That’s when I decided to apply for the Daily Bruin my fall quarter. Unfortunately, I was rejected, and after reading and rereading the list on the doors of Kerckhoff Hall 118, I finally gave up and sulked all the way back to my dorm room. I buried myself in bed with ice cream and Netflix. I laugh about it now, but at the time it was almost like a bad breakup.

Winter quarter rolled around, and although the foreignness of my surroundings died down, I still craved a feeling of comfort and home that I hadn’t found. I decided to apply to the Daily Bruin again, and prepared for what I expected to be another soul-crushing rejection. The outcome is probably obvious by now, considering I wouldn’t be writing about the end of an era if I wasn’t provided a beginning.

My days soon became a whirlwind of pitch meetings and occasional unnecessary arguments with my editors about why I needed to change my angle, or why I couldn’t possibly write an article that didn’t have a peg. It wasn’t until my third year when I became assistant editor and was on the opposite side of these arguments with my own writers that I realized how difficult I had made my editors’ lives my first year (sorry, Erin Nyren!).

But whether it was as a writer or an editor, DB gave first-year Sravya what she had been craving for so long. It gave me a sense of belonging and a sense of purpose. Whether it was coming up with pitches every week or addressing edits for the thousandth time because I was incapable of keeping my editors sane, I felt myself growing. I began to realize my passion for writing and found both my writers’ voices and my own. Although I didn’t find it enough to speak up in the office as much as I should have, I did become unapologetically firm and passionate about what I believed in – both in and out of my writing.

Becoming an editor my third year only strengthened this newfound confidence, and taught me a great deal of valuable lessons along the way. I’m not going to pretend like I never messed up – I did. But I also learned how to hold myself accountable for my mistakes, and when to ask for help. I realized the job of an editor is two-fold. You have to oversee your writers’ work and ensure your section is doing its part in keeping the paper running. But you also have to be their advocate – helping them grow the same way DB once helped you plant your own roots and flourish.

As I reflect on my four years at The Bruin and at UCLA as a whole, my heart is full of gratitude. I’m a different person than I was when I walked into this school four years ago, and I’m proud of the person I’ve become as I walk out now, four years later. And for that, thank you Daily Bruin. Not only did you help me find myself – you found me a forever home.

Jaladanki was a Blogging contributor 2015-2017, assistant Blogging editor 2017-2018 and a Blogging contributor 2018-2019.

Year in review: College admissions scandal, measles outbreak, Centennial Campaign

Another year at UCLA has gone by, and in between hustling to keep our grades afloat and maintaining energetic social lives, a variety of campus happenings have caught the eye of the media.

From a public health disaster to involvement in a scandalous college admissions scheme, UCLA is no stranger to national news headlines. Looking ahead to UCLA’s next 100 years, it will be difficult to forget these consequential events that put the action into the 2018-2019 school year.

Measles outbreak

Public health officials identified UCLA as a possible site for measles exposure April 22, after an infected student attended classes in Franz Hall and Boelter Hall earlier that month.

More than 500 people at UCLA were identified as potentially exposed to the virus. Of those, 119 students and eight faculty members were put in quarantine, and were released only after providing proof of immunization. As the week went on, the number of people in quarantine dwindled until there was only one on-campus student left and 27 left isolating themselves off-campus.

Students who were quarantined said the conditions were not just comfortable – they were fun. But there’s nothing comfortable, nor fun, about such a close encounter with measles on the smallest UC campus with the largest student body. UCLA was fortunate to have gotten away relatively unscathed – but without tightening vaccination requirements, our epidemiological future could be disastrous.

College admissions scandal

News broke out mid-March revealing UCLA’s involvement in one of the nation’s largest racketeering college admissions scandals. Men’s soccer coach Jorge Salcedo was revealed as a pawn in the bribery scheme that shook the world of higher education.

Salcedo received the transcript, test scores and falsified soccer profile of the daughter of Bruce and Davina Isackson from a former USC soccer coach. He forwarded the information to a UCLA women’s soccer coach and the student was admitted to UCLA as a student-athlete. Salcedo also received a $100,000 check in exchange for designating another student as a recruit for men’s soccer, despite the student never having played competitively.

The signature at the bottom of Salcedo’s hefty check was that of William Singer, the founder of the college preparation companies Edge College & Career Network and the Key Worldwide Foundation. Parents paid Singer a total of $25 million from 2011 through February 2019 to have their children’s standardized tests taken for them.

Coaches from USC, Stanford and Yale were also allegedly involved. The thing UCLA has in common with these three universities? They are all among the most highly-ranked institutions in the nation. For students, that’s a cause for concern.

In fact, two Stanford students filed a lawsuit against several of the universities involved, including UCLA, claiming that future employers might question the legitimacy of their degrees, coming from a university known to have had fraudulent admissions practices.

AFSCME strikes

In the past year alone, two workers unions – the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 3299 and University Professional and Technical Employees-Communications Workers of America 9119 – took to the picket lines five times to protest the UC’s unfair labor practices.

The first three strikes, in May 2018, October 2018 and March 2019, were in response to unfair wages, outsourcing, increased retirement age and health care premiums. The UC, however, claimed at the time that it offers AFSCME Local 3299 employees health care benefits at the same rate as other employees.

The fourth strike came April 10 after AFSCME Local 3299 filed an Unfair Labor Practice charge against the University for allegedly mistreating and intimidating workers at the picket lines during previous strikes.

Finally, on May 16, AFSCME held a systemwide strike at all 10 UC campuses in response to the UC’s alleged illegal outsourcing of labor.

Not only do the strikes cause quite a ruckus on campus, they leave students living on the Hill with limited dining options. While this seems like a small price to pay for the livelihood of the very people who make this university run, the ubiquity of these strikes is undoubtedly a disruption to students’ education.

Sexual assault lawsuit

On August 10, before the school year even began, a UCLA student filed a sexual assault lawsuit against two UCLA fraternities – Zeta Beta Tau and Sigma Alpha Epsilon.

These two fraternities, as well as the Interfraternity Council and ZBT member Blake Lobato, faced charges of negligence, assault, battery and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

According to court documents, the student attended a party at SAE and was then encouraged by Lobato to spend the night at ZBT since she was heavily intoxicated. After the student agreed, Lobato sexually assaulted her. Little was done by the then-ZBT president when the incident was reported to him. Only after the student filed through the Title IX office was Lobato expelled.

At the start of the school year, student government officials called on fraternities to hold themselves accountable for the predatory behavior that is so common in their culture. The council recommended that fraternity members undergo consent and intervention training as well as partake in a town hall to discuss issues surrounding sexual assault.

UCLA turns 100

This year marks UCLA’s 100th birthday.

100 years ago, our now-sprawling campus consisted of nothing but Royce Hall, Haines Hall, Powell Library and Kaplan Hall. This year, the quad in front of these buildings served as a primary location for the start of many centennial celebrations.

In celebration of UCLA Alumni Day on May 18, students and alumni gathered for performances in Fowler Museum, a TEDxUCLA event, lectures by faculty and alumni and a talk between Chancellor Gene Block and previous UCLA chancellors. The day concluded with a light show projected on the exterior of Royce Hall. Alumni Day was just the beginning of UCLA’s 14-month series of events and initiatives.

In honor of its centennial anniversary, UCLA also launched its “Let There Be” campaign to raise money for the university’s endowment and scholarships, as well as four other initiatives which aim to showcase UCLA’s archives and contributions to social justice in Los Angeles.

UCLA’s 100 years have come to show that it is no longer just UC Berkeley’s younger sibling. It is the nation’s No. 1 public university, with a presence that can be felt not just around the sprawling metropolis of Los Angeles, but across the world.

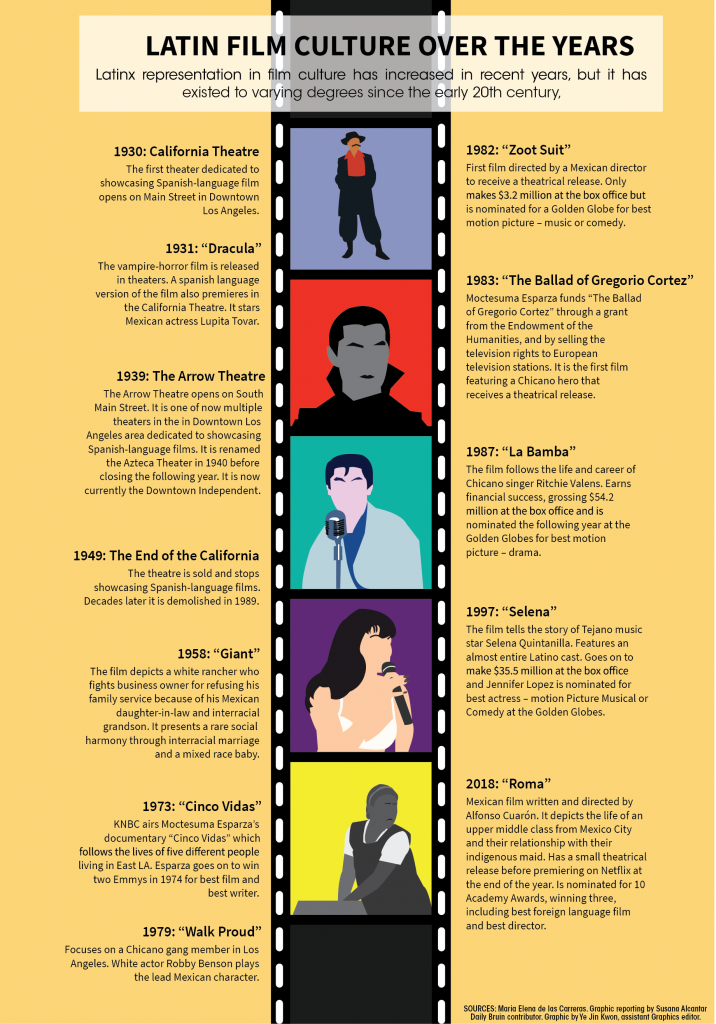

Latino representation in film remains limited, despite history of inclusion

This post was updated June 23 at 2:53 p.m.

Introduction

In February, Alfonso Cuarón was awarded an Academy Award for best achievement in directing for his film “Roma,” which follows the life of a middle class family’s maid in Mexico City.

Actress Yalitza Aparicio was the first indigenous actress nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role in the film. Additionally, “Roma” was the first Mexican film to win an Academy Award for best foreign language film.

But despite the steps forward, Latino representation in Hollywood remains limited.

White actors still make up 77% of the roles in the top 200 theatrical films of 2017, with minorities in leading film roles remaining under 20% from 2011 to 2017, according to UCLA’s Hollywood Diversity Report 2019. As of the latest report, Latinos, in particular, only make up a 5.2% share of all film roles. Compared to other minority groups, the report reveals that other minority groups also have limited representation, with black actors and Asian actors each representing less than 10% of the overall racial makeup in films.

Despite little modern representation, there is a long history of Latino representation within the industry, though it has not always been positive. In order to better understand the lack of modern Latino representation, the past must be taken into account to see where the industry is heading. From the downfall of the Spanish-language theaters that once populated Los Angeles to the rise of more diverse content from streaming services, the way the Latino population has been seen on the screen has evolved throughout the years.

The past

1930s

Physical theaters used to house much of the Latin American film culture of the time. In Los Angeles, South Main Street fostered a number of theaters dedicated to showcasing Spanish-language films, such as the Azteca Theater and the California Theatre. Theater businessmen and exhibition companies recognized the local audiences and showed films meant to make a profit in the area, said UCLA Theater, Film and Television lecturer Maria Elena de las Carreras.

“There was a Spanish-speaking audience, mainly Mexicans who saw images of themselves and of the motherland in these films in the theaters,” de las Carreras said.

As films with sound began to evolve, de las Carreras said Hollywood studios made Spanish-language versions of English films alongside original movies in Spanish – which were highlighted by the theaters. One of the films with a Spanish-language counterpart was the 1931 film “Drácula,” which de las Carreras said primarily followed the original film.

However, she said “Drácula” was more risque with the female lead, portrayed by Mexican actress Lupita Tovar, donning a revealing nightgown – the actress in the English version, on the other hand, wore a modest dress. Such depictions emphasized many cliches associated with Latin American culture, such as hyper-sexuality and passion, de las Carreras said.

Besides the Spanish-language adaptation of “Dracula,” some of the other popular films created include Carlos Gardel’s “tango” films, which were distributed by Paramount and became popular throughout Latin America. Mexico’s first film with sound, “Santa,” and films featuring popular comedian Cantinflas also appeared in theaters.

But the influx of Spanish-language films in Hollywood did not last long. The downturn was a result of economic, cultural and linguistic issues, de las Carreras said. In terms of finances, it ultimately became more economically viable to either subtitle or dub the film, as studios would only have to produce one film instead of two – diminishing the need to make original Spanish content, she said.

But there were subtler faults as well. First, American producers would have Latino actors from one country portray characters from a different country, such as an Argentine actor portraying Mexican characters. The producers generalized all Latino people, not realizing Spanish-speaking audiences would notice the mix of accents, de las Carreras said.

In a similar vein, sometimes studios would film at a Mexican estate and claim the film took place in Argentina, which de la Carreras said was noticeable to the Latin American audience.

As fewer Spanish-language films were produced, de las Carreras said the theaters disappeared soon after. The Azteca Theater was closed at the beginning of the 1940s and the California Theatre shut down by the end of the decade. By the 1960s, urban renewal caused the primarily Mexican and Central American populations in Downtown LA to be displaced. With a disappearing audience, de la Carreras said the theaters have since been demolished or transformed into evangelical temples.

1950s to 1970s

But Latino filmmakers and actors continued to work despite the downturn in Spanish-language films. During the 1950s, the predominant genre was still the Western, which initially gained popularity in the early 1900s. But many of the Latino characters seen in Westerns represented stereotypes, UCLA Theater, Film and Television professor Chon Noriega said.

“You have a lot of Mexican characters but … they are the convenient villain, or they are marginalized figure that a white Samaritan can come in and save,” Noriega said.

One example is the 1956 film “Giant,” where Mexican characters are depicted as working in poor conditions. At one point in the film, the main character – a white rancher – fights a man who refuses to serve his family at a restaurant because of his Mexican daughter-in-law and interracial grandchild. Noriega said the film was atypical in presenting a vision of social harmony through interracial marriage and a mixed race child, but it still did little to shift racial dynamics in the film itself.

In the 1960s, the Chicano Civil Rights Movement impacted the film industry, as they became more concerned about Latino representation and employment, Noriega said. They wanted to get people in front of and behind the camera.

Television became the main avenue for Latino representation, Noriega said, as there were more opportunities in television since it was regulated by the federal government. In order for stations to get their licenses, they had to be responsive to the surrounding community. The half-hour in between local news and prime time for programs was set aside to broadcast public affairs programs that were shown locally in all major U.S. cities, Noriega said.

It was a step forward – but Noriega said filmmakers still wanted to make feature films.

“It was a way to reach a global audience. Unlike televisions, (films) crossed borders,” Noriega said. “They wanted to be a part of that, and they wanted the Mexican American community to be a part of the culture of American cinema.”

Latin American films eventually found a resurgence in the mid-to-late 1970s. One of the pioneering Chicano producers at the time was UCLA alumnus Moctesuma Esparza, who created “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez” and “Selena.”

While at UCLA from the 1960s to the early 1970s, Esparza said he spent his time advocating for change as one of the founding members of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán at UCLA, an organization that seeks to promote Chicano unity and empowerment. He went on to create the ethno-communications program at the UCLA school of Theater, Film and Television in order to address negative stereotypes of people of color in media and their lack of representation in the film school. The program lead the film school to start accepting a critical mass of underrepresented students, opening the door for minorities to pursue careers in film and television.

He said he was fortunate enough to have the news station KNBC finance his graduate thesis, “Cinco Vidas.” The documentary follows five different people living in East LA, such as a gardener, attorney and grandma. The film went on to win two Emmys, and although he did not have any difficulties making the film, Esparza said his success was built on years of activism.

But upon graduating, Esparza said the only work he could find was as a crew member. Eventually, he met Rene Cardenas, the founder and executive producer of Bilingual Children’s Television, who gave him a job as a producer for a children’s PBS show, “Villa Alegre.”

“I was able to really get my real training in the craft and skill of filmmaking, and it was because of other Latinos and Chicanos that I got a break,” Esparza said.

Despite new talent emerging, the rise of Latino gang films in the late 1970s brought new, negative Latino stereotypes to the screen. Noriega said the gangster films follow a similar framework as the Western films. They are both action and conflict-oriented genres in which the law plays a significant role in resolving the conflict – and Latino characters were often portrayed as the bad guys. They both identify and explore real problems, such as racism and residential segregation, but they often exploited these issues that the Latino population was facing, he said.

“It’s the idea of looking at this population. We know they are here,” Noriega said. “We know they are a part of the country, but let’s do it in a way that keeps them as other, not us.”

Some gangster films, such as “Walk Proud” and “Boulevard Nights,” voiced the issues many Chicanos were advocating for, such as labor rights and educational access, which Noriega said led to rights-based movements being associated with lawlessness. “Walk Proud” exasperates the issue, Noriega said, because while the main character is Mexican, he is portrayed by a white actor wearing brown contact lenses.

“Those are legitimate demands that are being made on society and on the government. Suddenly, you have these gang films in which that language is the language that gang members are using,” he said. “It pathologized (those) social movements and you think, ‘Jeez, that’s pretty sneaky.’ You just made us seem like a bunch of criminals, when what we are doing is trying to fulfill the American Dream.”

1980s to 2000s

Moving into the 1980s, the first studio film written and directed by a Latino was Luis Valdez’s 1981 “Zoot Suit.” It was not a financial success, but it did receive critical acclaim, including a Golden Globe nomination for best motion picture – musical or comedy.

The first financially successful Latin American film was not released until 1987, when “La Bamba” made almost $55 million at the box office. Noriega said the film was successful because it was a typical Hollywood genre film – the music biopic. It provided the backstory for a song almost everyone new, while also featuring a mainly Latino cast, Noriega said.

Outside of studio films, the 1980s also saw the rise of independent Chicano films, some of which were produced by Esparza. One such film was “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez,” a biographical film based on a book by author Américo Paredes. Large Hollywood studios would not fund it, so Esparza said he first purchased the rights to the story through the National Endowment for the Humanities, then planned a theatrical release prior to a television release.

Few films were made throughout the 1990s and early 2000s as the Chicano Civil Rights Movement lessened. However, there were a few mainstream releases, such as the biopic “Selena,” which follows the story of Texas Tejano singer Selena Quintanilla and her rise to success.

Esparza, who served as the executive producer of the film, said it was his daughter who first encouraged him to purchase the rights to her story. However, he originally was not interested in making the film.

“I didn’t quite know how to tell the story because I thought that Hollywood would be more interested in the crime and I wasn’t interested in that in that kind of a story,” Esparza said.

But over time he realized that the story could be about the pursuit of the American Dream.

Esparza, working with the Quintanilla family, pitched the story to various studios, and ultimately struck a deal with Warner Brothers.

Esparza said he believes that the success of the film had to do in part because of the music appeal, but also because audiences saw a young, American Latina woman striving for the American Dream. In particular, Esparza said young Chicanas tended to view the film multiple times, as seeing a dark skinned Latina on the screen was a powerful image.

“It made young Latinas appreciate and love themselves. That influence, which acknowledges in a profound way the racism in our own culture, was beautifully over come just by the image of Selena,” Esparza said.

The present and future

New talent

The industry is changing, and many students aim to be a part of the change.

UCLA graduate screenwriting student Gregory Renteria said as a Latino and disabled man in the graduate screenwriting program, he has felt out of place because although he is white passing, he comes from a working class background, and many of his classmates come from upper middle class families.

(Joe Akira/Daily Bruin staff)

However, working with comedy has allowed him to focus on racial tensions in a more humorous manner and makes issues seem more universal, he said. Renteria grew up during the late 1990s and early 2000s watching Hollywood movies dubbed in Spanish on Univision and Telefutura. Though there weren’t many Latin American films at the time that he could watch, Renteria said Martin Scorsese’s films resonated with him because of their portrayals of urban working class life, Catholic symbolism, and utilize 1950s and ’60s pop songs. Renteria said his work reflects his Latino background.

“I tackle these subjects head on. This is my life,” Renteria, said. “This is the story of my parents and people all across California, Mexico and Latin America.”

He is currently writing a loose adaptation of the play “Accidental Death of an Anarchist.”The play is originally set in Italy during the 1960s, but Renteria chose to place the story in 1940s Los Angeles, following union workers and the influx of migrant workers from Mexico and the Philippines.

The film emphasizes the idea that whenever a tragic attack on U.S. soil happens, white Americans are quick to mobilize and persecute those who do not fit into the mold of being a white Christian, he said.

“I want to show that these processes of unfair treatment and oppression are typical,” he said. “It’s never just one time.”

Another graduate student emerging in the film industry is Brenda Lopez. Lopez associates her love of cinema with the image of Mexican actress Maria Felix, who has the same name as her late grandmother.

Now a UCLA graduate student in education and a filmmaker, Lopez’s research focuses on women of color in film school and how their experiences impact their career trajectory and self-reflection within the industry.

While an undergraduate at New York University, Lopez said she was often the only Latina in her classes, and had to figure out her own path to success. She grew frustrated, because she was taught to write or talk about what she knew but few people around her understood her experiences.

“Folks are looking for something that is going to be relatable to a large number of people, and when your story doesn’t right away catch somebody’s attention, or to them feels very foreign, it can be isolating,” she said. “I felt discouraged writing about those experiences because I didn’t have a community that I could count on.”

After receiving her bachelors of fine arts degree, Lopez decided to pursue her PhD in education. Her family valued education, and Lopez said she wanted to explore why there were so many Latino people in film school – where many industry professional find their start.

She said the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found in its 2017-2018 study of the highest grossing films from 2007-2018 that Latino folks were among the least represented populations in film. Documentaries provide an opportunity to highlight untold stories and allow people to share their experiences in their own way, she said.

Most recently, she created a documentary film about her family titled, “No Somos Famosos,” which challenges the idea that Mexican American families do not value education. When she asked her father to appear in her film, she said he questioned in Spanish why she wanted him – after all, he isn’t famous. Her community does not often have their story told, though their experiences are often echoed by many, she said.

And as a Latina telling her family’s story, she said she was able to bring a different perspective than if someone not of color had directed the film.

“There is this long history of writing about us as a community or our stories being told by people who have no business telling our stories,” Lopez said. “Who don’t understand what walking in our shoes is like?”

The Netflix effect

New talent is emerging. And according to Esparza, streaming services are at the forefront.

In the 1930s, physical theaters provided a platform to showcase Spanish-language content. In 2019, Netflix is taking on that role. De las Carreras said such services allow films that might not have successful theatrical releases to shine – “Roma” being one of them.

“Everyone I’ve talked to has seen ‘Roma,'” de las Carreras said. “Lesser known films or filmmakers that have had a harder time finding a theatrical release now can be seen in a streaming platform that is stunning.”

Traditional studios would not have wanted to make the film as it was, de las Carreras said. Instead, she said studios would have wanted to focus more on the maid and the troubled marriage of the couple, but Netflix was willing to provide a platform for the intended story focusing on how the maid navigates Mexican society.

Noriega said although it is a beautiful film it still focuses on an upper middle class family in Mexico. It introduces an indigenous female character who is central to how the family organizes itself, but is also on the margins of that same family.

“It’s not her story,” Noriega said. “It’s about recognizing the impact of her presence in their lives, which is a very different story, but that is the story (Cuarón) could tell.”

Esparza said one of the reasons why Netflix and other streaming services seem more willing to show Latin American content is because they are interested in targeting the younger generation. Thirty percent of people under 30 are Latino, and Esparza said their economic power serves as an incentive to cater to them.

Despite the success of some Mexican directors such as Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro, their accomplishments often make it seem like there is more Mexican American representation in film. But their films do not focus on stories of the U.S. Latino population, Noriega said.

For example, del Toro won best director and best picture at the Academy Awards for “The Shape of Water,” following a mute woman and an amphibious creature. Meanwhile, Cuarón won an Oscar for best director for the film “Gravity,” which is about two white astronauts stranded in space.

There are also no Latino actors who could be the main actor of a Hollywood film today, said Esparza. It means we are worse off in terms of talent than we were 60 years ago, he said. For example, in the 1950s and 1960s Latin actors like Gilbert Roland, Fernando Lamas, Ricardo Montalban and Dolores del Rio were all on screen.

However, there is hope that change will occur, Renteria said. Highlighting films such as “Roma” will help encourage other filmmakers to begin tackling issues such as colorism and class stratification, he said.

“‘Roma’ is not a perfect film, but at least it’s attempting to be critical, and I think that’s always the first step to better representation,” Renteria said.

Despite streaming services ushering in changes, Lopez said she feels pessimistic because of the long history of Hollywood not opening doors for the Latino community. However, she won’t stop fighting for that by bringing it back into a film school setting, as she wants aspiring filmmakers to have a space where they feel comfortable to write about their own experiences.

Ultimately, Esparza said students need to demand more representation within academia in order to gain the training necessary to thriving within the industry.

“We need to take over the film schools and get our students from our community into those film schools so they can get trained,” Esparza said. “It’s like wanting to be a lawyer or a doctor, and we have to support them.”