[raw]

Gender behavior therapy and gay conversion:

UCLA’s past, California’s future

Second-year cognitive science student Giancarlo Sanguinetti attended a gay conversion therapy session when he was 14.

Fifth-year architectural studies student Steven Shipley decided that he wanted to go to gay conversion therapy during his sophomore year at UCLA. After four sessions, his therapist disappeared.

What is Senate Bill 1172?

The original version of this article contained an error and has been changed. See the bottom of the article for additional information.

He liked playing with girls’ toys, he liked wearing dresses.

He told his parents he wanted to be a girl.

It was 1967, and his parents were worried. So between ages 5 and 8, Karl Bryant went to therapy at the UCLA Gender Identity Research Clinic every other Saturday, where he learned to act more like a boy.

There, Bryant met with UCLA psychiatrist Dr. Richard Green. They played games, talked about positive male role models. Green emphasized the benefits of being a boy, the challenges girls face.

Green encouraged Bryant’s father to develop a closer relationship with his son, taught both parents to create more conventional gender structures in the house, with the father making decisions, Bryant said.

The basic message, Bryant said, was, “You can wish you can be something that you’re not, but that’s not ever going to happen.”

“He said it took a few years to realize that he wouldn’t want the same treatment for his children, that the therapy did more harm for him than good.

Green was conducting a long-term study, which was in some cases supplemented by therapy, about the outcomes of young boys who displayed “gender atypical” behaviors. This means young boys who acted like girls, who said they wanted to be girls.

Green, who lives in England, could not be reached for this story despite multiple attempts to contact him via phone and email.

Bryant remembers getting along well with Green, meeting with him about once a year, until he was 20, as part of the study. He remembers that in their last meeting, Green asked if Bryant would want the same treatment for his children that he had received, if they displayed gender atypical behaviors.

Bryant said yes.

He said it took a few years to realize that he wouldn’t want the same treatment for his children, that the therapy did more harm for him than good.

Now 51, a professor of sociology and women’s studies at the State University of New York at New Paltz, and recently married, Bryant identifies as a gay man.

“I was told that the way I felt about that aspect of myself was wrong, was sick, needed to be changed,” Bryant said. “It was a little different than a kid on the playground threatening to beat you up – you know they’re the enemy. This was my parents, people I trusted.”

There is still a debate about how or whether to treat children who identify as a gender different than their biological sex. Though UCLA no longer runs this clinic, there is still a similar program run by University of Toronto psychologist Dr. Ken Zucker that treats young children and adolescents for what he calls “gender dysphoria.” The goal is often to help children feel more comfortable with their biological sex.

In California, a new law passed in September will prohibit any licensed therapists from trying to alter the sexual orientation of a minor – this includes efforts to change gender expressions, the way Green did.

The Clinic

Encino psychiatrist Dr. Larry Newman trained at UCLA from 1964 to 1969, where he became a professor of psychiatry.

He was part of the UCLA Gender Identity Research Clinic partly led by Green and fellow UCLA psychiatrist Robert Stoller, and Newman stands by the work they did.

About once a week throughout the 1960s and 1970s, mostly on Saturdays, a group of psychiatrists and psychologists would meet at UCLA and talk about cases relating to gender identity and patients who identified as transsexual. At the time, transsexual referred to a person who identified as a gender that is different from the sex in which they born, Newman said. Today, the same definition is used for the term “transgender.”

The Gender Identity Research Clinic at UCLA was most concerned with understanding gender issues and how transgender people came to be the way they are, Newman said.

“The goal at UCLA was never to change a child’s behavior, Newman said, but rather to find a way to give them the best chance at happiness in the long term.

While UCLA was one of the first universities to research the topic of transgender issues, it wasn’t the only one. One of the most prominent gender clinics of the period was at Johns Hopkins University, said Vernon Rosario, a UCLA associate clinical professor of psychiatry who has researched the topic.

The UCLA program wasn’t a clinic in the normal sense – there wasn’t a fixed location, there wasn’t a sign on a door, he said. They started at a time when clinicians were first trying to figure out how to treat patients with gender identity issues or questions.

They would talk to people – both adults and adolescents – informally, and only provided therapy if it was sought out, Newman said.

The goal at UCLA was never to change a child’s behavior, Newman said, but rather to find a way to give them the best chance at happiness in the long term. This involved therapy to discover the psychological root of a child’s tendencies.

For example, parents might come in with a boy who has been bullied at school for feminine tendencies and playing with girls. That child’s best chance for success at school might be to find another group of boys that have the same interests that he does, like a drama group, Newman said.

“Basically, we’re looking for what is out there, what can be done for the person, and that is never a simple issue,” Newman said. “Everyone’s an individual, every situation is different.”

Often, like in the case of Bryant, the goal was to make the child feel more comfortable with his or her biological sex.

In 1976, Newman wrote an article for the American Journal of Psychiatry titled, “Treatment for the Parents of Feminine Boys.”

In the article, he writes that young boys who display feminine behavior may grow up to be transgender or homosexual, and to avoid these outcomes their parents should discourage such behavior during the ages of 5 and 12, when they are most open to change.

Newman now says that a reason to provide therapy for children to make them more comfortable with their biological sex is to save them from the medical procedures and expenses that come from being transgender, he said.

Newman said he does not think there is anything wrong with being gay or transgender. He believes that sexual orientation is unchangeable, but gender is more fluid.

“Attraction and the object of your desires from a sexual standpoint, does not change,” Newman said. “Gender issues are somewhat different. They can change. They do change, over time.”

Newman said Green’s study proves this – most of the participants of the study who as children said they wanted to be girls grew up to identify as gay men over the next 15 years. Many of those participants became comfortable with their biological sex without therapy, Newman said.

Parents who put their children in the study could elect to have their children go through therapy, if they wanted these behaviors to change, said Bryant, who is now researching the gender identity clinic and efforts to change gendered behavior as a sociologist.

Bryant was one of those kids.

But Green himself didn’t provide therapy for all the children whose parents wanted it. He also referred some to George Rekers, then pursuing a doctoral degree at UCLA, who used behavior modification methods to change the behavior of gender atypical boys as part of his thesis.

Rekers’ methods included rewarding boys if they played with more masculine toys like trucks and toy guns, and instructing parents to ignore their child if he played with girls’ toys or exhibited feminine behaviors.

Rekers was not a part of the Gender Identity Research Clinic – he was in the department of psychology, while Green and Stoller, the other researcher who headed the clinic, were both psychiatrists at UCLA, Newman said.

The Law

A CNN series last year on the effects of Rekers’ work on some of those subjects is one of the reasons for the new law that Gov. Jerry Brown signed in September.

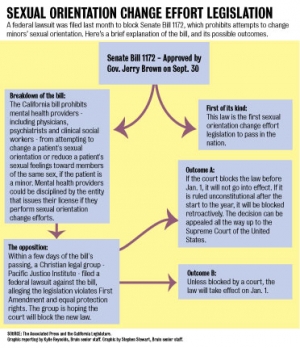

The California law, Senate Bill 1172, takes effect in January and prohibits any therapy meant to alter sexual orientation of minors, including therapy to change gendered behaviors.

State Sen. Ted Lieu saw the series that delved into the treatment of one of Rekers’ subjects, who later committed suicide. The subject’s family partly blames Rekers’ treatment, according to the CNN report. Lieu then decided to get to work on a law to prevent similar therapy, he said.

The main concern for activists who advocated for the law is religious gay conversion therapy, which is not what the UCLA Gender Identity Research Clinic was doing. Medical, psychological and psychiatric organizations have come out against gay conversion therapy, saying that it is ineffective and that sexual orientation cannot be changed.

Newman said once the law is implemented, he will probably stop seeing minors with gender issues altogether because an unhappy patient who is a minor could later accuse him of breaking the law.

This is a concern for more than a few clinicians who have patients who come to them with gender identity issues – even those practitioners who believe there shouldn’t be transgender or gay conversion therapy, said Rosario, the UCLA associate clinical professor of psychiatry.

“The real risk is that it now creates an area where most practitioners are going to say, ‘You know, it’s such a tricky area, I’m just going to turn away these patients,’” Rosario said.

Bryant, though, is glad the law passed.

“Parents have been able to get (minors) into therapy where the child or teen doesn’t really have any kind of autonomous notion of consent,” Bryant said. “This law would have protected me from that kind of intervention at the time.”

He said he spent years feeling ashamed of the quirks that he thought were just a part of his personality. But now that’s changed for Bryant. He’s writing a book about the history of treating gender variant children, and he’s involved in community activism to increase education and acceptance.

Last month, Bryant married his partner in New York.

Email Kohli at skohli@media.ucla.edu.

Correction: Dr. Ken Zucker is a psychologist.

[/raw]