Eitan Arom

UCLA students venturing into neighboring Santa Monica can testify that the city of sun, sea and shopping seems like a pretty happy place. But a proposal by the city’s mayor to create a “well-being index” for its residents seeks to answer the question ““ just how happy is it?

As one of 20 finalists in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Mayors Challenge, Santa Monica has proposed a happiness measure that incorporates factors such as physical health, social connectedness and community resilience. The competition seeks to underwrite an innovative project that can be replicated in other communities. The winner of the challenge will receive $5 million in funding, with four runners-up each receiving $1 million.

Thus, Santa Monica’s plan has potential policy implications for the city and any community that seeks to improve the well-being of its residents ““ UCLA included.

The proposal, successful or not, raises the question of how to minimize the cost of maximizing happiness. That principle is no less true at UCLA than in Santa Monica or anywhere else.

Should Santa Monica win Bloomberg’s competition and receive funding for its proposal, UCLA should pay close attention to the results of this experiment and consider adopting a similar approach to the well-being of the student population.

In other words, what services can student government, faculty and administration provide at the lowest cost to produce the greatest returns to the happiness of students?

After all, the tuition that each of us pays every quarter not only buys us an education but also membership in a community endowed with many privileges and services ““ prominent examples of which are gym and library memberships.

Of course, such a task is neither an easy nor a simple one. Happiness, as we can all attest, is hard to put down to numbers and equations.

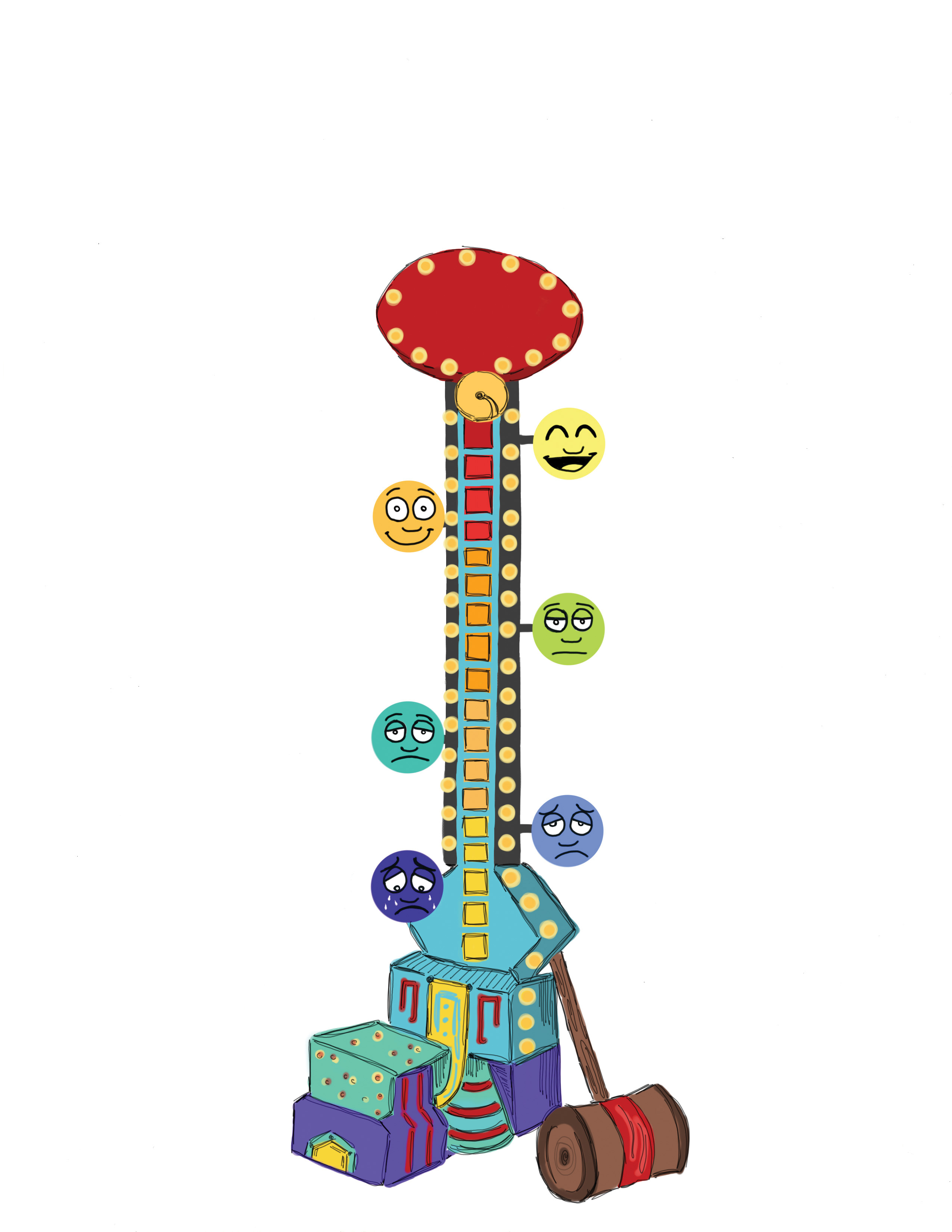

Nonetheless, several researchers at UCLA have set out to quantify subjective well-being, and with some success. In his recent book, “Engineering Happiness,” Rakesh Sarin, a professor in the UCLA Anderson School of Management, even goes so far as to introduce the concept of “happydons,” an incremental unit of happiness, and a “happiness seismograph” to measure an individual’s happiness around the clock.

“These measurements are not as precise as measuring height and weight, but they are a lot more precise than the average person might think,” Sarin said.

Sarin’s research, besides yielding some common sense results, proves the point that in some sense, happiness can be captured in so many mathematical equations.

These tools are an expedient way for a city (or a campus, for that matter) to know as much as possible about what makes its people happy.

Admittedly, the well-being index may seem like yet another attempt at social engineering from the city that saw a push to put a circumcision ban on the most recent ballot.

But seeing as the role of any government is to maximize the well-being of its constituents at the lowest possible cost, knowing what makes those constituents happy is of utmost importance.

If this campus were to take up that charge, it would become a pioneer in producing happy students.

Sarin said that measures of happiness are currently accurate enough to imply the necessity for simple policy prescriptions such as decreasing commute times for residents.

For UCLA, Santa Monica’s proposal raises the question of how to fine-tune services to best improve the student body’s subjective well-being.

The point is that educated decisions are better than uneducated ones: Knowledge, as the old cliche goes, is power.

Santa Monica’s proposal embodies that philosophy and in doing so serves as an exemplar for shrewd governance ““ an example UCLA would do well to follow.

Email Arom at darom@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to opinion@media.ucla.edu or tweet us @DBOpinion.