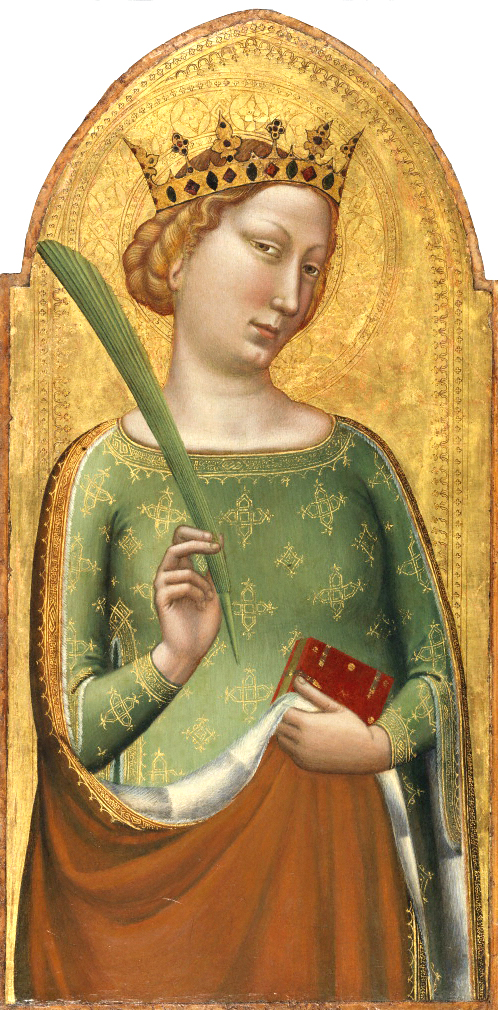

Artist Bernardo Daddi’s 1340 work, “A Crowned Virgin Martyr.”

(FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO)

Giotto di Bondone, born in Florence, Italy during the late Middle Ages, created this piece, titled “The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures” in about 1320.

(WILDENSTEIN & CO.,INC., NEW YORK)

It’s a familiar ensemble ““ an extremely large Virgin Mary holding the infant Christ, while a brigade of disproportionately smaller saints and patrons frame the throne, all with shiny gold discs mounted behind their heads in a way that is somewhat reminiscent of medieval art.

But the work isn’t medieval; it’s early Renaissance art. As a part of the current featured exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum, “Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance,” the fourteenth-century piece, along with the rest of the exhibition, shows stylistic changes, including more realistic facial expressions, made during the transitional period from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance.

The exhibition features several artists from the early Renaissance, including Giotto di Bondone, who was especially known for his influence in the art world as a forerunner of incorporating human emotions in devotional artwork. Panel paintings crafted prior to the Renaissance typically included subjects that were extremely stiff and impersonal.

“There’s definitely a shift that happens around 1300 because of Giotto,” said curator Christine Sciacca. “He’s taking a step to depict figures as humans, to try to show that they’re fleshy, that they have human bodies under their drapery and to show the relationship between figures.”

In the painting with the enlarged Virgin Mary, officially titled “The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures,” Giotto depicts interaction between the infant Christ and a nearby saint, a feature that he adds in order to humanize divine subjects in this version of the Madonna Enthroned.

In addition to Giotto’s paintings, altarpieces done by Pacino di Bonaguida show a change in style through facial expressions made by the subjects he painted. In particular a devotional piece done by Pacino, “The Crucifixion,” depicts Christ being crucified along with religious figures at the bottom grieving with a great sense of sorrow on their faces.

Despite differences in each artist’s work, the collection as a whole resembles a very specific style that reflects both old ideas, including the stiffness of medieval art and new ideas, such as the introduction of emotion and expressiveness. Developing distinctive styles particular to each artist was not yet an idea that was universally practiced.

“There is no concept yet of (an) individual artist having to stake his name like a kind of brand. Artists worked in workshops, and they learned within the workshop traditions,” said Meredith Cohen, a UCLA art history professor. “All the other younger junior artists would try to copy the well-known artist. There was a kind of goal they were working towards, and to some degree innovation was discouraged.”

The exhibition also incorporates informative panels on the science behind conservation and restoration. Having endured centuries of life, the collection underwent conservation in an attempt to show the work in its original brilliance.

“Restoration has some kind of purpose, motive or agenda behind it. What people are trying to do now is conservation,” Cohen said. “The idea to conserve or preserve the image, but prevent further damage. The idea is now to do the least amount of change on the actual artwork.”

The “Chiarito Tabernacle” is a triptych panel painting by Pacino. The panels on each side have significantly faded shades of vibrant blue to charcoal black, while the centerpiece features gold leafing that remains in good condition.

“Altar pieces often fade over time … but removal of dirt and soot that have built up on the surfaces of the works of art … (reveals) some of the original colors,” said James Fishburne, an art history graduate student at UCLA. “Many of the paintings in the exhibition include gold leaf. Gold is inert and will not fade, but other colors, such as yellows and some blues, will degrade as time passes.”

Conservators and conservation scientists at the Getty involved with the exhibition have paid particular interest in trying to convey what the pieces looked like originally before the effects of environmental influences and previous restoration attempts. As an aid to their endeavors, illustrated manuscripts that are presented along with altarpieces and paintings, such as an early version of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” act as a guide in terms of pigmentation of panel artwork.

“The manuscripts are often better preserved because they’ve been closed up in books and not exposed to light or smoke,” Sciacca said. “By looking at the manuscripts, it tells us a lot about how panel paintings might have looked originally.”

The copies of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” also serve as a link between the religious and secular world that reflects the change in artwork during the transitional stage between the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

“At this time you also have humanism developing in Florence, so you have this interest in learning about the ancient writers, an interest writing about the human condition, and of course Dante’s text is still based in religion,” Sciacca said.

“But it’s also a piece of secular literature and this interest in human beings and how they function in society. There seems to be a lot of religious paintings, but it still relates to the secular world.”

Email Jeein at jshin@media.ucla.edu.