Dialysis machines filter waste and water out of the blood for patients with failed kidneys. The process takes several hours a couple days a week.

It’s a little after 6 a.m. and Mikey Hann walks into the waiting room with a bright smile on his face. As he grabs a cup of coffee he makes jokes with the nurses, familiar friends. He even does a little jig, winning a smile from everyone around him.

The 38-year-old from West Los Angeles is here for dialysis.

His kidneys don’t work.

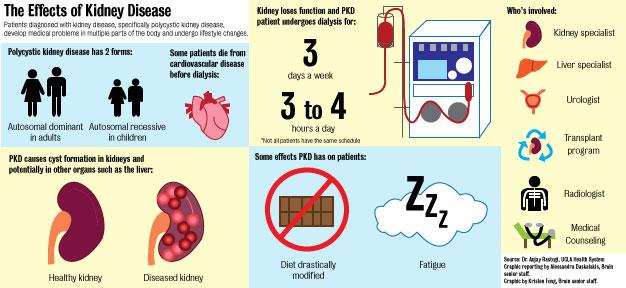

So he comes to DaVita Dialysis on Santa Monica Boulevard three times a week for about four hours to get hooked up to a machine that does the work for his kidneys ““ filtering and removing excess waste and water from his blood.

“I feel like my body is 70 or so, but my brain is like a 25-year-old,” he said.

A team of UCLA doctors has been trying to start a centralized program at UCLA for some time now, with a more formal push since this summer, to help patients like Hann and spur research about the complex diseases.

Mikey’s story

Hann transferred to UCLA from Boise State University in 1995 pursuing a degree in psychobiology.

For years Hann, who struggled with undefined health problems, felt there was something wrong with him, but he never had proof and no doctor could ever figure it out, he said.

He tried everything he could to improve his health, not knowing the cause.

He bought a juicer, he exercised and he ate all sorts of things that are healthy but coincidentally not good for people with kidney failure, he said, with a laugh.

Some days his feet would be so swollen his shoes wouldn’t fit.

Some days he would work a short shift at a restaurant after sleeping for most of the day and feel like he had run a marathon.

When he was diagnosed in the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center emergency room three years ago, he said he felt relief finally knowing what he had.

“It was like a lightbulb,” he said.

He started dialysis right away.

Doctors still don’t definitively know what he has, Hann said. It’s possible he has a variation of polycystic kidney disease, a condition where cysts form on the kidneys and potentially other organs, compromising function.

Hann refers to his doctor, Dr. Anjay Rastogi, as his “Yoda.”

Polycystic kidney disease is the third most common cause of kidney failure and the most common inherited cause of kidney disease, said Rastogi, director of the UCLA Dialysis and Chronic Kidney Disease Program and medical director of the Living Donor Program.

“There is no treatment. Once diagnosed, (patients) wait for “˜it’ to happen,” Rastogi said. “What’s “˜it?’ Ending up on dialysis.”

Supporting through a center

Rastogi first became involved in the push for a polycystic kidney diseases center at UCLA after giving talks to the public about kidney donation and talking to patients and potential donors.

Some patients die from cardiovascular disease before they make it to dialysis.

The disease is so complex, a common complaint from patients is that they know more about the disease than their primary physicians do, Rastogi said. Easy access to specialists is a necessity.

“When I was diagnosed in the emergency room, there was a level of comfortableness because I knew I was at (a UCLA medical facility),” Hann said.

Since UCLA is a leader in kidney transplants in the nation, creating a center makes sense, Rastogi said.

The center will provide an important opportunity for doctors to focus on research, said Dr. Gabriel Danovitch, medical director of the UCLA Kidney Transplant Program and colleague of Rastogi.

The center will start as a clinic running out of 200 Medical Plaza in Westwood, Rastogi said. He plans for it to be up and running by March.

Still, a comprehensive center will require time and extensive funding, Rastogi said. Right now his personal team is raising money for the center through grants and donations.

The doctors on the team hope to eventually provide comprehensive medical care, education, outreach and research to individuals affected by the disease, Rastogi said.

Laughter as medicine

To help pay for his out-of-state tuition as a transfer student, Hann started working at restaurants and bars, trying to make ends meet. Eventually he and his roommate, Grant Belding, became interested in comedy ”“ Hann decided to make it a career. He never finished UCLA.

Around the time Hann started working at the Second City Network in Hollywood, an improvisational comedy club famous for comedians Tina Fey and Steve Carell, among others, Belding was diagnosed with kidney failure.

Belding returned to his home in Houston and the roommates maintained a close friendship.

Hann would fly out to meet Belding once a year to talk comedy.

When Belding was in dialysis he would call Hann on his cell phone and say, “Hey, how’s it going? I’m at the spa.”

Hann would reply, “Oh, you’re getting your oil changed?”

Belding died from cardiovascular disease five years after he was diagnosed with kidney failure.

Having been diagnosed, himself, months after Belding’s death, Hann said he feels the roommates’ friendship was not a mere coincidence.

“Spiritual people might say I was supposed to meet (Belding),” Hann said. “I was lucky because someone showed me the way.”

Because of his schedule and the physical strain of his condition, Hann couldn’t maintain a position as a stand-up comedian, so now he works as a stage manager at the Second City Network.

As he waits for a kidney transplant, Hann remains cheerful. He said he has never liked the stigma associated with dialysis.

“Believe me when they say laughter is the best medicine,” he said.

Looking forward

Hann is currently on a waiting list to get a kidney transplant.

“I’m not going to spend my time and energy worrying,” he said. “I’ll wait for the next (kidney), the right one.”

He is considering returning to school to study kidney disease in an academic environment and wants to work with Rastogi in the future to start a nonprofit for patients with kidney failure.

For now, he will take life as it comes.

Lying down in the dialysis chair, he watches television and mentions the popular song “Gangnam Style.” The song’s introduction, when the singer is lying in a lounge chair, reminds Hann of how his dialysis should be ”“ happy.

He wants to find a way to change the way people look at dialysis, and get rid of the “die” in it.

When people get cancer, they fight for their lives. But with dialysis, it seems as though people have given up, he said.

“I’m on “˜life-alysis.’ I’m here,” Hann said.