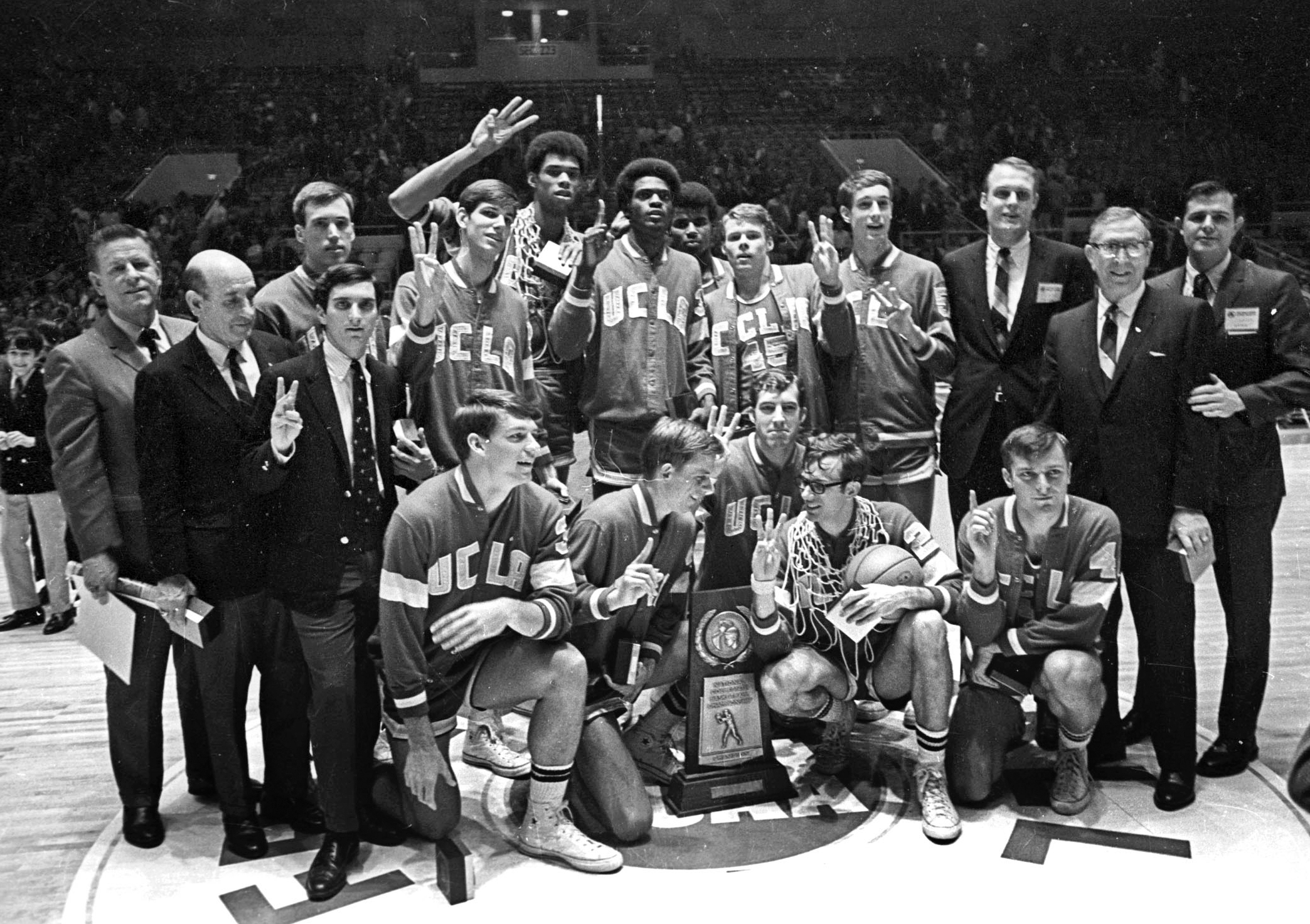

Courtesy of UCLA Athletics

The 1969 Championship team, including Ken Heitz (right of the trophy) and John Vallely (left). Heitz died from sarcoma this past summer.

Dribble for the Cure is an event that took place on the UCLA campus this weekend to raise money for pediatric cancer. Young participants were joined by UCLA’s basketball team as they began the walk at Drake Stadium, which continued around a designated path through the UCLA campus.

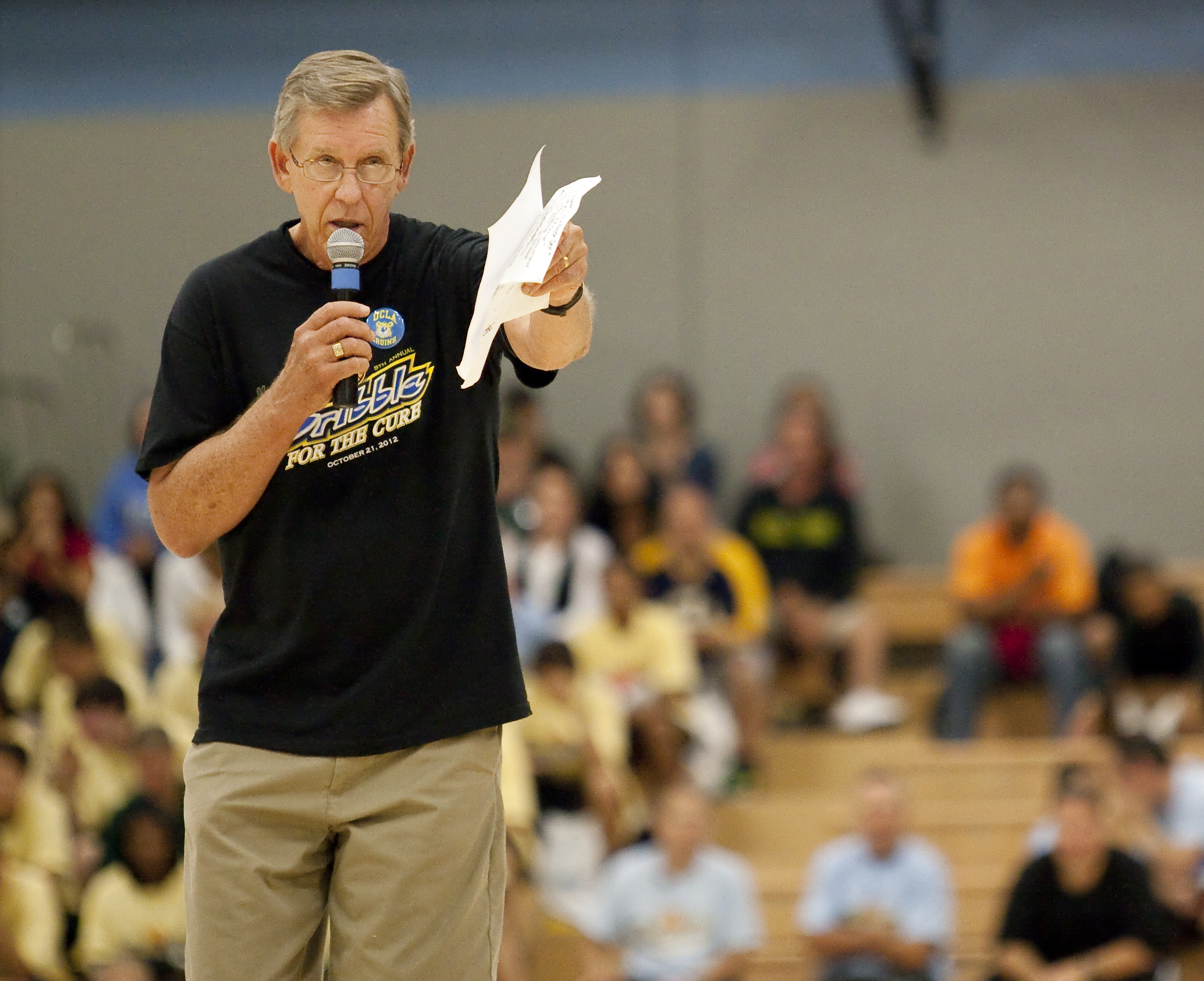

Former UCLA basketball player John Vallely speaks to audience members in the Wooden Center at the fifth-annual Dribble for the Cure.

In the photo of the UCLA men’s basketball team celebrating its national championship victory in 1969, Ken Heitz squats next to the trophy, holding up three fingers ““ representative of his third championship as a Bruin.

To his left, John Vallely takes a knee next to coach John Wooden, with one finger in the air ““ signifying his first NCAA championship.

But now that number three that Heitz once held is of stark importance to Vallely. Three of his closest have battled cancer ““ Heitz, Vallely’s daughter, Erin, and Vallely himself.

And the number one now represents Vallely ““ the lone cancer survivor of the group.

“When someone says all you have to do is be tough and you can beat cancer, that’s a bunch of bull ““ cancer takes out the best of us. And so it’s just unfortunate that we lost Ken to sarcoma and we lost my daughter, Erin, to sarcoma,” Vallely said.

Vallely was a starting guard at UCLA for two years after transferring from Orange Coast College. In both his years as a Bruin, he captured the NCAA championship. After two years at UCLA, Vallely was picked in the first round of the 1970 NBA Draft by the Atlanta Hawks.

But the battle on the hard court was incomparable to that of his teammate, his daughter and himself.

Erin Vallely died in 1991, and Heitz lost his battle with cancer this past summer. John Vallely is a survivor of non-Hodgkins lymphoma.

When Erin Vallely battled cancer, John Vallely immersed himself in the battle against pediatric cancer.

His daughter was diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma, a cancer of the muscle tissue, at age nine. She died at age 12.

Since Erin was diagnosed, her father has been on the board of directors for the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation to raise money for pediatric cancer research.

And through the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation, Vallely partnered with Mattel Children’s Hospital and his alma mater to bring a fundraiser for pediatric cancer, called Dribble for the Cure, to UCLA.

“We couldn’t do this without UCLA,” said Jeri Wilson, Executive Director of the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation.

“The whole team there between UCLA and Mattel’s Children does the lion’s share of the event because its cancer research is hosted on campus there. So John’s the one that took it to UCLA and they picked it up as one of their signature events.”

Participants dribble a basketball along a designated course through campus. Half of the money raised goes to Mattel Children’s Hospital at the direction of Dr. Theodore B. Moore, and the other half goes to the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation.

Sunday, the fifth-annual Dribble for the Cure took place in honor of Heitz, who died in July after battling sarcoma for eight years.

Vallely lauded Heitz for his intangibles as a teammate, as the type of player that was championed by Wooden.

“He was that kind of guy that was willing to do whatever it took,” Vallely said. “The final game against Purdue University there was a star on the other team, a fella named Rick Mount. Mount was really a great shooter … but he had to deal with Ken Heitz the night of the National Championship in 1969. And Kenny caused him to go 12 for 37 from the floor.”

And as for Heitz’s stat line?

“He didn’t score a single point in that game, but he was instrumental in the success of us becoming national champions in 1969.”

Vallely and Heitz had a unique relationship in that both had to learn to transition from their natural positions at forward to guard. And later in life, both had to transition from health to fighting cancer.

“This was a kind of guy that was not only my teammate on the basketball court but a teammate in life,” Vallely said.

***

Dr. Moore, Division Chief of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology at Mattel, took the microphone at Drake Stadium with two boys to his side. He spoke of the trials and tribulations for children diagnosed with cancer.

And then he turned to his left and introduced two survivors to the crowd and the rhythm of bouncing basketballs, often at the hands of other kids in the midst of their own fight with cancer.

“They’re in the middle of a very intense competition, it’s a competition for their lives and the stakes are never higher than that,” Dr. Moore said. “… They deal with the problem they have and then they go on with life because they know that each day is important and they never know which day could be their last.”

Though they are in the literal fight for their lives, the children were all smiles. Laughter and shouts of glee filled the entire course.

The two boys who stood beside Dr. Moore at Drake were 15-year-old Patrick Aghaian and 14-year-old Aaron Rutz.

Both were treated for pediatric cancer at Mattel Children’s Hospital.

They stood in the Wooden Center as the event wrapped up, soaking it all in. Families ran around, junior center Josh Smith played basketball with groups of children, high schoolers dribbled basketballs around the court, all to come together for the cause of pediatric cancer.

For the boys, who had gone through so much in their fight against cancer, who had spent so much time alone in a hospital room, the outpouring of support showed them that they did indeed have so many people by their side.

“It’s a huge thing for kids who are going through it, or who recently went through it. When I was in the hospital, I felt alone, like no one but my parents cared,” Aghaian said.

“But now I see that a lot of people really do care.”

And there’s no question about what college they want to go to.

“(UCLA) is my second home, I couldn’t be happy if UCLA wasn’t here. … People here took care of me,” Aghaian said.

Aghaian and Rutz not only share a dream of attending UCLA, but of becoming doctors.

“Before I didn’t know what I wanted to do, now I want to come to UCLA and go to medical school,” Rutz said.

The experience he went through at Mattel directly affected Aghaian’s choice of profession.

“I want to go into the medical field, kids get sick and I want to help them when they really need it.”

***

Dribble for the Cure gave kids facing similar adversities the chance to come out and be a kid again.

“(These kids) don’t want to be in isolation, they don’t want to be tired. They don’t want to not be able to eat. They just want to be a kid,” Wilson said.

But through research being funded by the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation, toxicity levels in chemotherapy have greatly diminished.

“I think the difference between when Erin was diagnosed years ago to now is that the therapies are much less toxic on kids,” Wilson said. “… Erin could live a productive life today. If Erin were diagnosed right now, there’s a pretty good chance she would still be around.”

But looking up at the kid with the microphone provides Wilson with the most hope.

“I think what’s special for me is all the work that goes into it when you can see, a little boy ““ young man ““ standing up there and he can say, “˜I know I’m not alone doing this and you guys care,'” she said.

And looking at crowd, all onlookers could see were kids. They weren’t divided by who had cancer and who was healthy ““ they could run around and play, just kids for the day.

***

Vallely played for coach Wooden for two years but the impact was lifelong.

In the hallway of his home and in his office, the Pyramid of Success is on display. He said he’s implemented it in every aspect of his life.

Competitive greatness is the hallmark of the Pyramid, and Vallely channeled it to defeat his own battle with cancer.

“Whenever something comes up, what are the things that we can control? I can’t control cancer. I can’t control a victory even. I can only control my effort.”

***

After giving a speech about his experiences with the disease and the importance of Dribble for the Cure that brought the entire crowd to its feet, Vallely paced around the Wooden Center while children lined up for autographs from UCLA athletes.

He stood at the center of the court, spellbound by the spectacle around him.

When asked what Heitz would have thought of the event, Vallely said, “He’d say “˜I’m so happy to be part of this.’ I think he’d be really happy that his legacy was helping others. And so doing this sort of project … would make a real positive for him in his life.”

And as for Erin?

“She would say, “˜Daddy, you just keep goin’ and gettin’ it.”

Email Nguyen at cnguyen@media.ucla.edu.

Email Coghlan at ecoghlan@media.ucla.edu.

Editor’s Note: The print version of this article only contained half of the full version of this story. The article began on the main page of the Sports section and was supposed to continue on page 9. Another story in that day’s newspaper was repeated in the position where this story should have appeared.