The original version of this article contained an error and has been changed. See the bottom of the article for additional information.

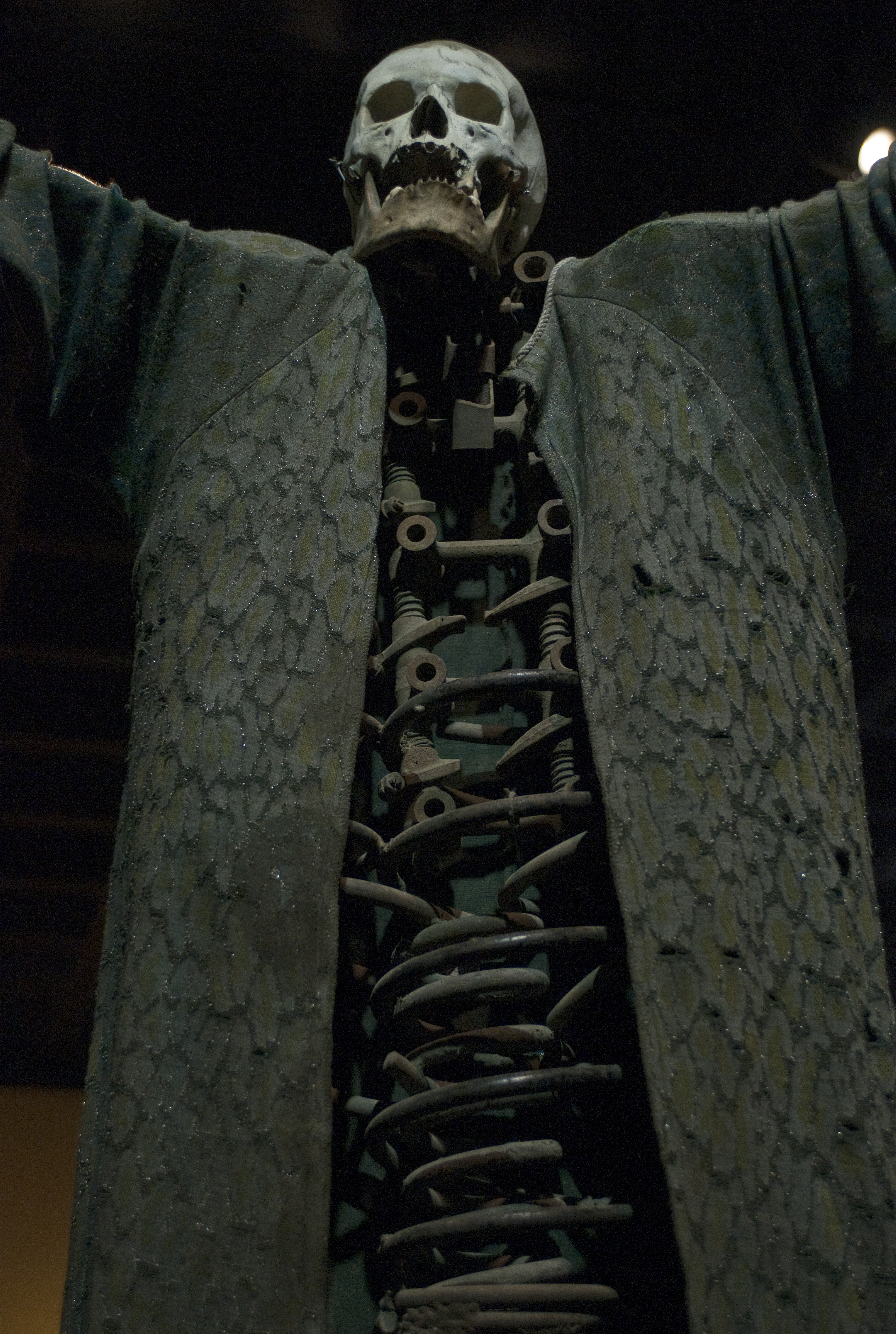

A tall, looming skeleton with arms spread open reveals its scrap metal rib cage and welcomes its guests as they shuffle silently through the Haitian art gallery. Iron crosses, coffins, oil paintings and beaded portraits of the past intensify into greater modern images of death and suffering. However, these dark pieces tell more than merely a tale of woe.

For the Haitians, the past 10 years brought extensive death through a consistent cycle of social violence and natural disasters. As a part of the Fowler Museum’s recent exhibition, “In Extremis: Death and Life in 21st-Century Haitian Art,” the frightening works mentioned above created by artists from the Haitian slums are contrasted with older, more idealized art created before the disasters ensued.

“Some may find it weird, but this is what they do,” said second-year economics student Kirk Psara while looking at a sculpture of a skull plastered onto a retro television.

The Gede family, Vodou’s most revered deities, represent the cycle of life and death as well as hope and justice. One beaded flag shows a man dancing and clicking his heels together despite the skull and crossbones beside him. In a recreation of a shrine painting by Jean Philippe Jeannot, a Gede dressed in a fancy suit dances on a coffin. The Gede family emphasizes that death should not be feared but celebrated.

However, as a result of modern disasters, the Gede family’s strength and loyalty is questioned. In an acrylic painting by Didier Civil, one member of the Gede family stands, pale-faced, with her back turned as if she were reluctant to help. Another piece, this one a massive beaded flag by Myrlande Constant, depicts the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake with collapsed churches, dead bloody bodies and the Gede family crying on its knees, overwhelmed and helpless by the massacre.

“How do you respond to a situation that gets worse and worse?” said Patrick Polk, world arts and cultures lecturer and a curator of the exhibition. “The image of death is direct and gives a form to contemplate. … There is always an inherent hope of the possibility (of) new life, … but now (in the modern view) even death is getting uglier and more frightening.”

Polk said that many Western audiences are disturbed by Haitian artwork because they actively avoid death whereas the Haitian populace considers death to be a celebration. He also said that Western audiences commonly believe that Vodou consists of black magic and evil witch doctors because of fabrications within popular culture.

“They have created art that simply has no market,” said Donald Cosentino, curator of the exhibition and UCLA emeritus professor of black Atlantic religions and popular culture. “Art describing a romanticized past and idyllic deities (are) out the window. (But) it is interesting to look at how the (street survivors) make sense of (the chaos).”

To emphasize the change in the viewpoint of the artists, a large cross constructed of televisions contains screens that show different images of explosions and carnage. These physically and metaphorically separate the old artwork, and perspective, from the new. Following the cross are dark portraits with what seem to be fingernail scratches across the canvas and beaded flags that show scenes of death and devastation.

In the “Artists of the Grand Rue” portion of the gallery lies a climactic maze of statues, all with heads made from human skulls, smiling with missing teeth and portions of the body made from rusty car parts, abandoned shoes and bicycle frames.

Although these images may seem shocking, Cosentino said that the recent transformations in Haitian deity worship accurately reflect their adapting religion.

“African religions are … so cosmopolitan,” Cosentino said. “It’s a living religion that changes and always has new forms and guises.”

And even though these current artists crafted sculptures and paintings of suffering and abandonment, Polk said the religious imagery in their artwork demonstrate that they still accept and have some faith in the afterlife.

“The Gede family … tell it like it is,” Polk said, “They acknowledge the existence of death, … that it’s going home, it’s natural, (it’s) inevitable. … It’s more positive and something to be laughed at, or with.”

Correction: As a part of the Fowler Museum’s recent exhibition, “In Extremis: Death and Life in 21st-Century Haitian Art,” the frightening works mentioned above created by artists from the Haitian slums are contrasted with older, more idealized art created before the disasters ensued.