UCLA women’s basketball coach Cori Close chooses not to take walk-ons to her team.

On top of managing a schedule that simultaneously involves coaching and recruiting, many coaches at UCLA have the task of an accountant on a strict budget.

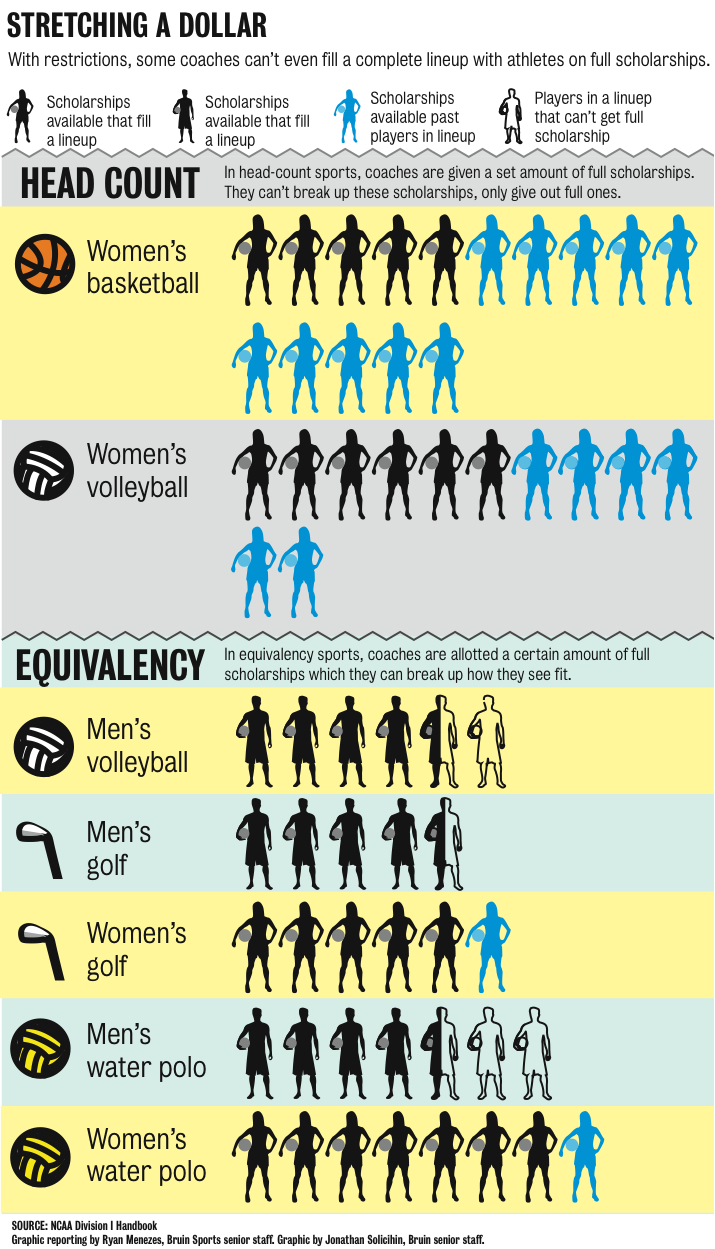

For those sports defined as “equivalency” sports by the NCAA, scholarships are broken up into fractions and the concept of a full ride is basically a fantasy. While some teams get to hand out scholarships in full, most cannot because of scholarship limits that couldn’t field a starting lineup.

Article 15 of the NCAA Division I bylaws spells out the restrictions on financial aid that teams can give student-athletes. Specifically, it sets out the limits that hamstring teams. All sports are not on equal footing in the eyes of the NCAA and the difference in the ways scholarships are awarded reflects as much.

Men’s water polo coach Adam Wright is in charge of one of the many equivalency sports, with a pool of four-and-a-half scholarships in athletic aid in a sport that requires six field players and one goalkeeper, not including backups. His job is to allocate the scholarship money across his sizable roster, which has numbered close to 40 players in each of his four years as coach.

“It’s an absolutely tricky thing,” Wright said. “You want to make sure you have something in reserve every year for recruiting. It’s a little bit of an art.”

Most sports at UCLA fall under the equivalency category. Men’s volleyball has a similar limit of four and a half for a roster half as sizable as the men’s water polo roster. Baseball is capped at 11.7 scholarships, with the added caveat that no player receiving athletic aid can be given less than 25 percent of a scholarship.

For men’s water polo, Wright’s roster currently carries 37 players, with around 20 actually dressing for games. When the scholarships are divided, most players on the team come to UCLA with less than 30 percent of one.

Men’s golf coach Derek Freeman, who is spreading his four-and-a-half scholarships among 12 players this season, said he looks at a recruit’s financial situation before deciding how to dispense his scholarships.

“I try to educate (recruits and families) on the importance of wanting a team that can spread the financial scholarships around for families that really need the help, families that may not be able to come to UCLA otherwise,” Freeman said.

The circumstances around equivalency sports mean schools can get into bidding wars over the percentage of a scholarship offered to a player, something Freeman doesn’t take part in.

“It happens in our sport as well. It’s just not something I do as a coach,” Freeman said. “We make an offer and that’s what our offer is. It doesn’t change based on if another school offers more. … All of our guys want to be at UCLA. That’s the beauty of what we do.”

In contrast to Freeman, Wright recruits his players on a need-blind basis. He rarely looks for recruits outside of California because a partial scholarship has even less of an effect when out-of-state tuition is a factor, and also because most water polo talent is found nearby.

Sometimes coaches are fortunate enough to find parents willing to pay their child’s way through college and avoid taking scholarship money. Those cases are rare, leaving coaches to hand out scholarship amounts not necessarily proportional to talent level ““ though they do have the option of upping the athletic award at the end of each year.

“That’s something I always talk about when I go into a home ““ that the amount I can give you does really no justice for what you put in but it’s the nature of men’s water polo,” said Wright, echoing the sentiment of many coaches of equivalency sports. “Hopefully it’s something that will change, but that’s where we are.”

This breaking down of scholarships does not apply to “head-count” sports, which are allowed to give out only full scholarships. There are six such sports at UCLA: football, gymnastics, men’s and women’s basketball, women’s volleyball and women’s tennis. Football, the breadwinner in terms of generated revenue for most schools, can carry 85 scholarship players per team, the most of any sport by far.

Regardless of the scholarship situation, teams save extra roster spots for walk-ons. The use of non-scholarship players varies, but they can usually fit into the team picture by participating in practice or providing extra depth for a team, and do so without the financial commitment that counts against the scholarship limit.

Some walk-ons aspire to earn a scholarship and see regular playing time. While those in the equivalency sports can do this by earning partial scholarships, it’s a more daunting task in the all-or-nothing head-count sports.

The football and men’s basketball teams use enough walk-ons to form scout teams, meant to run through the opposing team’s plays in practice. There have been plenty of recorded cases of walk-ons moving up the ranks from scout teams to scholarships and prominence, the dream scenario for an athlete willing to foot the bill early for a payoff later on.

In other sports the task is tougher. Women’s basketball coach Cori Close rarely, if ever, carries a single walk-on. It’s a controversial move that shrinks the pool of women’s players. Like most other teams in her sport, Close prefers to recruit a scout team of men capable of challenging her team.

“If you’re trying to further the game, you want to challenge your players so their competitive habits become greater and greater,” Close said. “To add five walk-ons that really can’t mimic and challenge at that level, we have decided that’s not as good of an investment.”

Whether they are a walk-on in the truest sense or on a partial scholarship, for most athletes at UCLA the financial burden is on them and their families to cover the costs of going to school. Scholarship limits keep the playing field level in competition and keep coaches constantly scheming while recruiting.

“You’ve got to get athletes that want to come here for more than (aid),” Wright said. “It’s a bit of a give and take, and you have to explain that to recruits.”