Nicole Mirea

Last month’s appointment of Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels as president of Purdue University raised an important and controversial question: Are politicians or academics better-suited to run America’s public university systems?

In response, a group of Purdue students, faculty and alumni has staged protests at the university on the count that Daniels is a statesman, not an educator.

While the protesters make a valid point, some political experience could prove useful to a university leader. Large public systems like the University of California should find a balance between the two, entrusting internal matters to academics and external affairs to politicians.

As public universities’ budgets become increasingly entwined with complex legislation, presidents and governing board members with at least some political experience might be a solution for struggling university systems.

One example of the narrowing gap between legislation and learning is Gov. Jerry Brown’s tuition freeze proposal, which ties $125 million of state money for the UC and California State University systems to a tax increase on November’s general election ballot. It would seem public universities must now actively campaign actively to voters for funds.

Adept politicians already know how to draw voters and lawmakers to their sides. Completely divorcing politics from higher education is unrealistic, especially in the context of a public university that depends on state funds to survive.

Granted, a university completely run by politicians risks compromising academic neutrality through the politicians’ involvement in various campaigns. Likewise, the more business-minded board members and administrators could be charged with putting the bottom line ahead of educational quality. A university’s mission, first and foremost, should be to educate students.

But administrative leadership in which both political and academic backgrounds operate with equal influence can ensure the university stays true to its basic purpose. The most effective presidents can move through both spheres seamlessly.

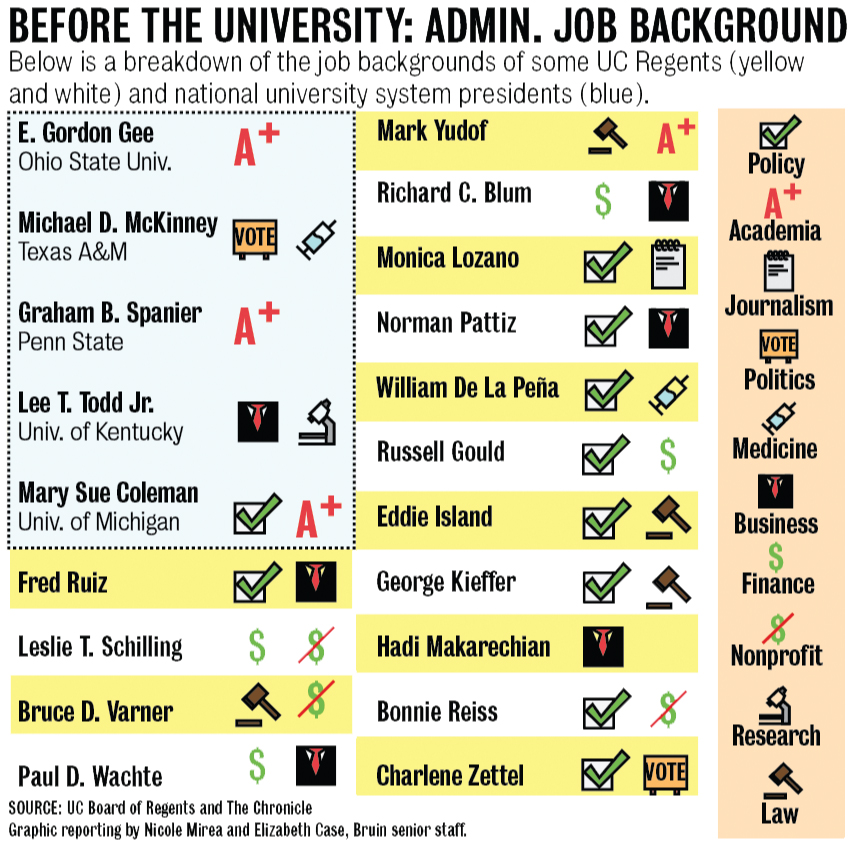

With his dual background in academia and politics, UC President Mark Yudof might be such a president.

Before his 2008 appointment as president of the UC system, Yudof was a law professor and administrator of the University of Texas at Austin, as well as head of two other university systems in Texas and Minnesota.

His political experience consists of a two-year term on the U.S. Department of Education’s Advisory Board of the National Institute for Literacy, in addition to a stint on former President George W. Bush’s Council on Service and Civic Participation.

This experience gave him the practical knowledge to successfully launch and implement his Blue and Gold Opportunity Plan, which lets students whose family incomes fall below $80,000 attend the University of California without paying tuition or system-wide fees.

Under Yudof’s guidance, other UC programs have remained largely intact even though the state’s annual contribution to the system has decreased by over $1.2 billion since the 2007-2008 school year, with the help of furloughs and tuition increases But while presidents usually attract most of the praise and criticism that accompanies system-wide decisions, the groups that select those university presidents are arguably more powerful and more politicized.

“More recent battles (have been) less about university presidents and more about appointments to governing boards equivalent to our regents and the activities of those boards,” said Dan Mitchell, professor at the UCLA Anderson Graduate School of Management and Luskin School of Public Affairs.

Under the California Constitution, the 26-member UC Board of Regents has full powers of organization and governance over the UC, subject only to very specific areas of legislative control in order to ensure the state’s money goes to the right places within the system. Seven ex-officio members serve on the board as by virtue of their other offices, including the governor, the lieutenant governor and the speaker of the assembly, as well as the UC president. There are also a single student regent and two regent-designates from the Alumni Associations of the UC.

The other 18 regents are all appointed by the governor of California and confirmed by the state senate for 12-year terms. There are 18 positions and three vacancies right now.

The governor consults with a 12-person advisory committee before making his recommendations for the Board of Regents, but the committee contains only three members who aren’t appointed by either the Legislature or the governor himself. It comes as no surprise, then, that most of them have some sort of political experience, whether in the form of lobbying, lawmaking or as an elected official.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. A politician intimately familiar with the state Legislature has the best chance of knowing how to win the most public money for the UC system.

However, balance should be struck in a university administration between politicians and academics who have experience within the faculty as professors and department chairs ““ a medium difficult to maintain given the current appointment system.

“We need people who understand both the inner workings of education and who understand how contemporary universities operate,” said Bob Samuels, a UCLA lecturer and president of the UC lecturers’ and librarians’ union.

Most of the regents are businesspeople who were not necessarily chosen because of their academic experience, Samuels added.

At first glance, it may seem like entrepreneurs and politicians both have management and negotiation skills useful for public universities.

However, we should remember that for public universities, the money should not be a final goal, but simply a means to an end ““ a well-educated population.

By nature, state universities are connected to their state governments. While the UC might have relative autonomy, the appointment process for the regents ensures that most of the university policymakers are also connected politically to the state government.

Politicians do have their place in academia, but it takes an experienced educator to run a university. A state university should seek to honor the balance between its political roots and its academic purpose.

Email Mirea at nmirea@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to opinion@media.ucla.edu or tweet us at @DBOpinion.