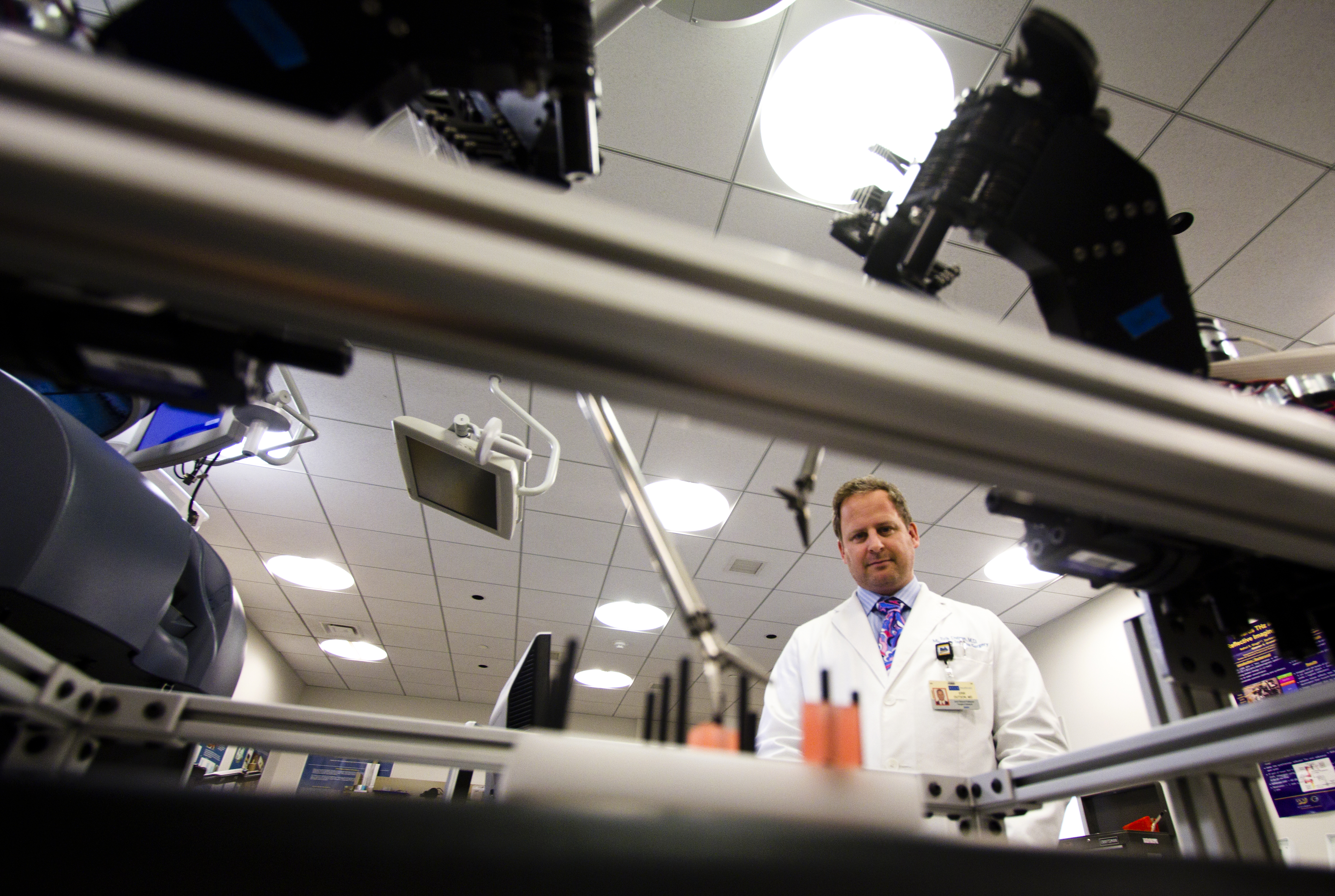

A model poses with the da Vinci Surgical System, a robot used in operations.

Courtesy of Intuitive Surgical, INC.

Clarification: The original version of this article was unclear. Dr. Erik Dutson is the executive medical director for UCLA’s Center for Advanced Surgical and Interventional Technology.

Standard surgery ““ that of large incisions, permanent scars and teams of gloved and scrubbed doctors who hover over their patients on the operating table ““ may soon give way to something else entirely.

Over the past decade, there has been a shift toward the use of robots in a growing number of surgical disciplines.

UCLA has been at the forefront of these advancements. The hospital system recently bought its fourth da Vinci Surgical System, a $2 million robot used by a relatively small number of surgeon elites to perform minimally invasive procedures.

The da Vinci robot has arms that hold up to three instruments and a camera, which are inserted in a patient via incision. A surgeon controls these instruments from a remote computer terminal, guided by a three-dimensional live-stream from inside the patient.

Using the robot is “a lot of fun ““ almost like playing a video game,” said Dr. Oliver Dorigo, a gynecological oncologist at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine.

Dorigo said da Vinci has advantages over even the most skilled human hands. It operates in hard-to-reach places with extreme precision and dexterity, and it filters out physiological tremor in a surgeon’s movements.

Early studies show da Vinci operations are just as successful as open surgery, and because only small cuts are made with the robot, the time it takes a patient to heal is greatly reduced, Dorigo said.

Dorigo assisted in a groundbreaking robotic operation to remove the uterus, vagina, urinary bladder and rectum from a patient with recurrent cancer.

“These procedures usually involve a tremendous amount of blood loss,” Dorigo said. “But this patient did so well she actually wanted to go home the next day.”

In some medical specialties, the transition away from open surgery is well underway. For example, about 85 percent of prostate removal surgeries are now performed robotically.

Carey Melcher had robot-assisted surgery for prostate cancer at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center in 2009.

For Melcher, this was an obvious treatment choice over chemotherapy or invasive surgery, which would have cut open his pelvis.

“I really had no concerns going in,” he said. “I arrived at the hospital early on a Monday morning, they did the surgery and by the next day I was out.”

Applications for robotic surgery are increasing rapidly. As new operations have been discovered, UCLA surgeons have been sent out to train in the latest approaches.

Abie Mendelsohn, a UCLA head and neck surgeon, traveled to the University of Pennsylvania and later to Belgium in spring to observe how da Vinci was being used to treat throat cancer.

He said he came back ready to operate with the robot himself, and now he is helping develop curriculum for UCLA surgeons-in-training to follow suit.

At UCLA’s Center for Advanced Surgical and Interventional Technology, researchers are working on what Dr. Erik Dutson, executive medical director for the center, calls “the operating room of the future.”

Robots play a large role in this vision.

One of the center’s goals is to create sensory feedback for the da Vinci system, said Chris Wottawa, a biomedical engineering graduate student who is involved with the project.

This would allow surgeons to feel an instrument as if they were handling it themselves, Wottawa said. Currently, surgeons must rely on visual cues when performing surgeries with da Vinci.

The center also works with robots still in the research stage. Weeks ago, the lab received one of seven Raven robots ““ which look like scaled down versions of da Vinci ““ that were created by an engineering team at UC Santa Cruz and the University of Washington.

Although the Raven has fewer capabilities than da Vinci, its smaller size could make it ideal for performing battlefield surgeries from a remote location, Dutson said.

Actual implementation of remote robotic surgery is still years away, he added, but the technology has been evolving at an exponential pace.

Dutson said he expects the robotic revolution to bring surgery and medicine up to speed with the pace of modern technology.

“We’re at least 20 years behind what everyone else is doing with computers,” he said. “I’m still writing down patient info on a paper chart. That’s absurd.”

Dutson envisions a future where robots can perform automated portions of procedures under a surgeon’s guidance, similar to autopilot in an airplane.

New technologies may also allow patients to be scanned and digitally replicated, so surgeons could practice complicated operations in a dry-run format, Dutson said.

“There are still concerns being raised about costs and practicality, but every year robotics is becoming more and more prominent,” he said.

Worldwide, more than one million procedures have been performed with da Vinci ““ a third of these in the last year alone, said Christopher Simmonds, senior marketing director for Intuitive Surgical, the company that manufactures the robot.

Since 2000, da Vinci has been the only robot certified for use by the Food and Drug Administration. Competitors, though, are racing to catch up.

“We are at the very beginning of where this journey will take us,” Simmonds said. “But I think a couple decades from now people will look back and say, “˜Did we really used to open people up?'”