At the start of each term, large universities like ours give the publishing industry a pretty generous gift in the form of required reading lists. As first week rolls around, lines in Ackerman Union stretch to lengths that seem more at home at a Black Friday sale than in a bookstore stocked with academic texts.

Yet those lines are tiny compared to how long they would be if we all got our books from the bookstore. Bruins, like the rest of America, are increasingly seeking alternative routes of access to the written word.

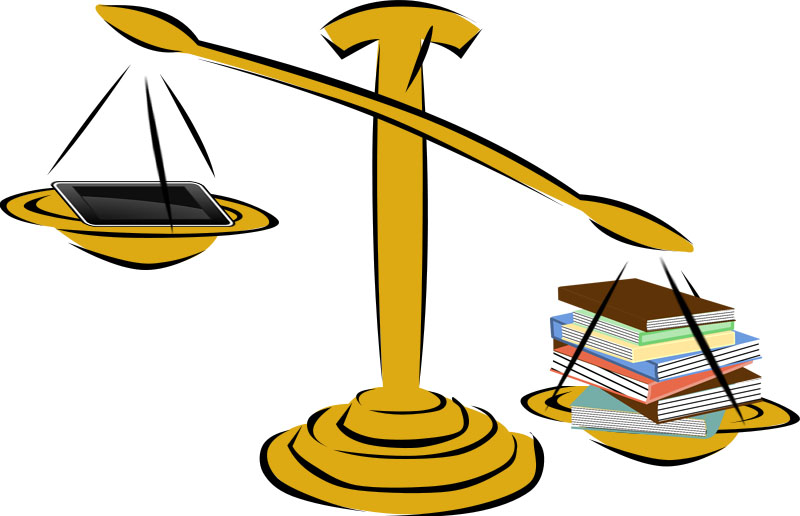

But there is one way in which students, usually trendsetters by virtue of our age, are actually lagging behind the general population. Although we do seem to have gotten the hang of online book shopping, and while most of us are hopelessly dependent on digital access to academic journals, students still don’t seem to be transitioning to e-books for all their apparent benefit.

Universities should be prime real estate for the expanding e-book market, but for the most part students are clinging to the traditional book form.

Yet despite an increasing number of consumers hopping on the bandwagon ““ with Amazon selling more e-books than printed books and the e-book market at the brink of breaking $1 billion in revenue ““ students don’t seem to be convinced.

A 2010 OnCampus Research Electronic Book and E-Reader Device survey found that 74 percent of students still prefer printed books over their digital counterparts, and only 13 percent of the students surveyed bought an e-book of any kind within the past three months.

E-books really should be a no-brainer.

They have search functionality that makes even the most thorough indexes obsolete. You can cram all those bulky textbooks into one elegant device and end up saving money. And they aren’t subjected to the same space constraints that force traditional printing to excise a lot of possibly important information, said Eugene Volokh, a professor at the UCLA School of Law.

Then, why the reluctance? The primary reason is that the technology to make e-books the most efficient tool for students just isn’t there yet ““ a fact that is hard to believe these days.

The serious students approach reading effectively as a vandal. With the bare minimum of a pencil in hand (some even carry an armory of color-coded highlighters, Post-it pads and paper clips), they deface the page in conversation with the text, underlining, highlighting and filling empty space with marginalia.

E-readers are, for the most part, unequipped for this kind of heavy-duty annotation. The basic task of highlighting is still far more cumbersome than in the traditional book form.

Even Apple, usually a byword for intuitive interface design, has yet to create a system of seamless annotation that can seriously compete with the ease of marking up a physical page.

Obviously e-books have a lot of potential in this area, with their promise of compactness, clarity and unlimited space. But as of now, paper still rules the game.

Furthermore, e-book technology is increasingly calcifying into a single-column monochromatic format. The e-book industry needs to provide academic publishing houses with more layouts that can accommodate the intimidating complexity of the science textbook, allowing for colored images and maybe even multi-layered presentations that allow for copresent notes and illustrations. Instead of, say, parentheticals that direct you to illustrations, or superscripts that usher you to a footnote, these things could be accessible through a simple click or hover, without disrupting your place in the text.

This is one thing the e-book establishment has missed out on. On the eve of the digital revolution, students had dreams of a complete renovation of traditional textual presentation. We envisioned a thorough marshaling of digital gifts. We wanted multimedia. We wanted the e-book to transcend the limitations of paper and become its own medium entirely. But for the most part, the e-book is just a digitized codex.

Back in the UCLA classroom, there is one thing I definitely can’t wait to bid goodbye ““ the course reader. These overpriced compilations of photocopied books could obviously benefit from an “e-treatment.” They should be less bulky, less costly and, one would hope, of better quality. It really is a scandal that I have paid more than $100 for some course readers photocopied from originals that have already been highlighted and marked up.

Although the UCLA bookstore has taken a step in the right direction in offering e-book options for certain books, it will not replace its printed book sales until the e-book has been perfected as a tool for students.

So this is an open letter to the industry. In a time when household spending on reading has been steadily declining for the past few decades, students provide a source of consistent revenue.

Solve the above problems and our business is yours for the taking.

Are you buying e-books? Email Dolom at rdolom@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to opinion@media.ucla.edu.