Griffith Observatory is not a well-kept secret.

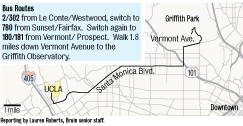

Even in the blustery cold, cars snaked down the side of the dusty hills of Griffith Park as my friends and I raced to the top of the hill to catch a coveted ticket to the last planetarium show of the day. A full parking lot and a mile walk later, we did not make it. However, even among a throng of visitors, Griffith Observatory is a gem.

It may very well be the only place in Los Angeles with a decent view of the night sky and one that showcases more than a handful of stars.

The observatory takes its name from its benefactor, mining and real estate tycoon Griffith J. Griffith, who wanted to provide Los Angeles with a park that could rival those he admired in Europe. When he offered the 3,015-acre park grounds to the city of Los Angeles in 1896, the city council was hesitant to create a park so isolated from the city’s population of 100,000.

Luckily, they changed their minds and the observatory was eventually built on Griffith’s donated land in 1933, along with an Astronomers Monument built by six sculptors employed by a federal public works program.

The palatial observatory’s three gray domes are an iconic fixture in Griffith Park and just a stone’s throw away from the Hollywood sign. The structure is a star itself, having served as the climactic backdrop for James Dean in “Rebel Without a Cause” and more than 40 other films and television shows. A James Dean bust sits on the observatory’s lawn, commemorating the actor and the building’s connection to film.

It’s an easily photogenic subject. The observatory overlooks the sparkle of downtown Los Angeles and West Hollywood with arguably the most expansive (and romantic) view of the city.

The Griffith Observatory is most famous for its telescope and planetarium shows, second only to its spectacular real estate.

And while I sought out these attractions twice, both attempts proved unfruitful.

During my first visit a few weeks ago, clouds obscured too much of the sky and the telescope was locked shut. This time, a line deep with eager parents and children in gleeful choruses of “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” prevented me from reaching the front.

But by chance, I was fortunate enough to visit the same night as the Los Angeles Astronomical Society’s monthly public star party. The society, which is comprised of amateur and professional astronomers alike, meets not by specific day, but according to each month’s moon phase, usually at half phase.

It was a lucky encounter ““ the astronomers work with the most authentic star map in Hollywood. Dozens of giddy astronomers stood watch over telescopes of every size, focusing their gear on sights of Jupiter’s stripes, double stars, magnified moon craters and even the questionable blur of a separate galaxy.

The building’s interior is equally impressive, with ceiling murals of the history of science painted by artist Hugo Ballin from 1934 to 1935. A Foucault pendulum swings a 240-pound sphere below the mural, swinging back and forth to measure the gradual rotation of the earth. Educational presentations are plentiful, including the shocking buzz of white hot spindles from Tesla coil electricity demonstrations.

For the nocturnal, the museum stays open long past typical museum hours ““ until 10 p.m. And aside from distant parking, our decision to brave the observatory on a busy Saturday night turned out well. It seems not all that sparkles is on the boulevard.

Email Roberts at

lroberts@media.ucla.edu if Los Angeles gets you starry-eyed. “Artscapes” runs every Wednesday.