When Judy Chicago came to study at UCLA in the late 1950s, she encountered an L.A. art scene that was largely male-dominated. Even so, there was something special here, she said, that allowed her as a female artist to make art and be herself.

“There was freedom from the shadows, freedom from the market,” Chicago said. “And that was irreplaceable.”

Two survey-style exhibitions at the Getty Center, which include Chicago’s work, open on Saturday as a part of “Pacific Standard Time,” a major cultural initiative that explores postwar artistic production in Southern California.

Organized into sections by theme, the Getty exhibitions showcase a vibrant and pluralistic artistic output in postwar Los Angeles.

“We knew that we wanted to do things that were temporal, ephemeral and, a lot of the times, something we weren’t supposed to do,” said L.A. artist Gronk.

The main exhibition, “Crosscurrents in L.A.: Painting and Sculpture, 1950-1970,” surveys painting, sculpture and other modes of art-making from L.A. artists working at that time.

The first room of the exhibit is a colorful display of a type of abstract painting called hard-edge painting.

According to principal project specialist and consulting curator Glenn Phillips, instead of New York’s abstract expressionist painting, Los Angeles had abstract expressionist ceramics and its own brand of abstract painting.

These paintings and their crisp forms were usually the result of using tape to achieve sharp edges. But many were done free-hand to create the appearance of taped-off edges.

And not all were characterized by straight lines ““ Helen Lundeberg’s “Blue Planet” depicts amorphous rings and shades of blue and brown enclosed in a circular form, which is on a vivid blue background.

Playing with perception and perspective is one factor that blurs the distinction between painting and sculpture in the exhibition.

Well-known L.A. artist David Hockney is represented by his famous poolside diving-board painting, “A Bigger Splash,” as well as “Man in Shower in Beverly Hills.”

“He was just creating this picture of what life might be like here (in Los Angeles),” Phillips said.

Other pieces on display include Vija Celmins’ “Freeway” painting of the 405 Freeway, Larry Bell’s “Untitled, Wall Piece” glass cube and Chicago’s “Car Hood,” a Corvair car hood spray painted with a design.

Many of the works, both paintings and sculptures, made use of new materials that emerged at the time, such as polyester resin and acrylic.

The second exhibition, “Greetings From L.A.: Artists and Publics, 1950-1980″ is a survey of artists that consists primarily of small-sized works of art.

While most of the documents on display in the two rooms are postcard-sized, the ideas behind the material covers are large.

The exhibition is divided into themed sections which include sections devoted to public censure, commercial culture, art school, anti-war activism and feminism.

The exhibition focuses on the relationship between artists and the public, according to curator John Tain of the Getty Research Institute.

“(The exhibit) deals with the way artists address the audience and create the audience,” Tain said.

Some pieces on display include humorous art show invitations created by the artists themselves, as well as a poster for a 1961 exhibition called “War Babies,” which drew outrage at the time for depicting an American flag as a table cloth with a black man, a Jewish man, a white man and an Asian man seated around it, each eating a food item thought of as stereotypical of their respective cultures.

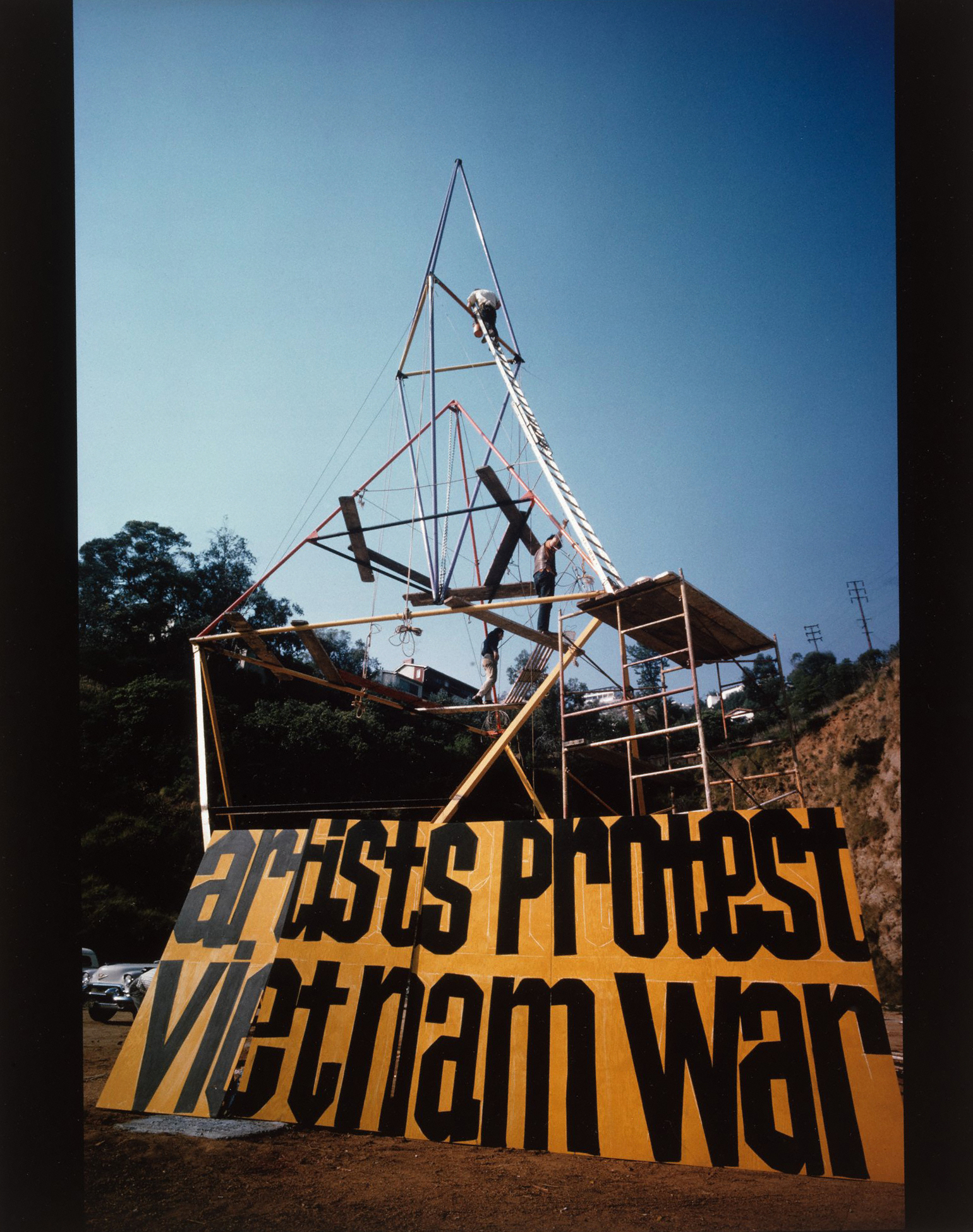

Also viewable are documents from the Feminist Art Program, the first of its kind, founded by Chicago at the California Institute of the Arts, and photographs of facets of the anti-Vietnam war effort, including the Peace Tower installed in 1966 on La Cienega and Sunset boulevards.