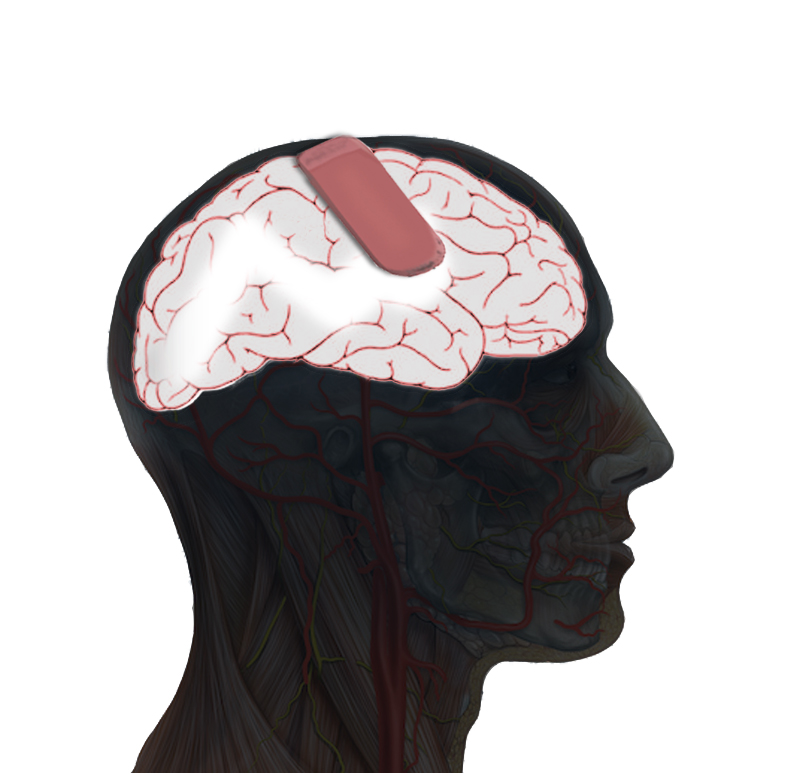

UCLA cellular neuroscientist David Glanzman’s research has provided new insight into the mechanisms of long-term memory.

CREDIT : UCLA NEWSROOM

Correction: The original version of this article contained an error. Alcino Silva’s group discovered treatments for neurofibromatosis type 1.

The marine snail’s siphon, a tube-like organ used for breathing, contracted for about a second when touched. The seemingly normal response would not surprise the average person, but David Glanzman was beyond excited.

The UCLA cellular neuroscientist and his research team knew they had successfully erased a long-term memory they had given the snail.

“It’s one thing to read about a scientific phenomenon, and it’s another to see it in our laboratory,” Glanzman, a professor of neurobiology and integrative biology and physiology, said.

They previously taught the slimy animal to contract more strongly using electric shocks, but after the inhibition of an enzyme called protein kinase M, the snail forgot what it learned.

Being able to erase memory through knowledge of a memory molecule could have serious clinical applications for humans, including the ability to treat diseases related to memory such as Alzheimer’s and drug addiction.

Rayad Barakat, a physiological science graduate student who has worked in Glanzman’s lab since he was an undergraduate student, said he remembers the first time they erased memory in a marine snail and how that opened up a lot of possibilities for the future.

About a decade ago, Glanzman read about the experiments Todd Sacktor, a professor at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, performed on rats and the proposal that protein kinase M plays a role in learning and memory. Glanzman said he formed his idea to experiment on snails at that time.

Because of their simple nervous system, marine snails are useful in studying memory before studies move on to more complex systems.

Glanzman and his team began this study two years ago, but his team wanted to do more than behavioral testing.

“We took it a step further,” he said.

First, Diancai Cai, Glanzman’s research associate, pulled out neurons from marine snails and placed them in a dish, creating a circuit composed of only two neurons. In contrast, the human brain has about a trillion neurons, Glanzman said.

The team effectively created and erased memory in the dish, something no scientists have done before. They strengthened connections between the pair of neurons, which showed the creation of memory, then they inhibited protein kinase M. This inhibition “erased memory” by reversing the number of new connections.

Cai spent several months learning and practicing to do something as difficult as extracting the neurons ““ keeping them healthy and allowing them to connect to each other. He said he has now done about 160 such experiments successfully. The Journal of Neuroscience published a study on these experiments on April 27.

Understanding how memory works is important to unraveling the mysteries of consciousness.

“Ultimately, what we want to do is explain consciousness in terms of brain function. I’ll be long dead before we do that,” Glanzman said with a laugh.

Memory is a common area of interest in the Brain Research Institute at UCLA, said David Jentsch, the institute’s associate director for research.

The Brain Research Institute is among the oldest and largest institutions devoted to studying nervous systems in the world, Jentsch said. Members such as Glanzman come from many different fields and have made important progress in understanding memory.

Glanzman said he helped form a memory focus group in the Brain Research Institute so people can come together to discuss their research and become better known through their collaboration.

In 2010, Susan Bookheimer’s lab was able to show that changes in a specific part of the brain can predate the decline into Alzheimer’s for people genetically at risk. And Alcino Silva’s group discovered treatments for neurofibromatosis type 1 and for tuberous sclerosis in recent years. Both are currently being studied in humans.

“Bring multiple experiments together, and these threads emerge that weave a fabric of science from a sea snail to the schizophrenic patient,” Jentsch said.

By boosting protein kinase M in the brain, Glanzman said it might be possible to bring memory back and treat Alzheimer’s, while inhibiting it could erase certain memories such as those causing post-traumatic stress disorder.

But first, scientists must learn how to identify specific memories in the brain so treating diseases does not interfere with memories such as a person’s fifth birthday party, Glanzman said.

Meddling with memory, however, could raise ethical questions.

“If we do go in and change people’s memories, it’s going to have to be heavily regulated by the (National Institutes of Health) and state agencies,” he said.

Glanzman said science is quite far away from reaching that day, but it certainly seems possible.

“Science proceeds in steps,” Glanzman said. “In our study, we haven’t come close to solving the problem of how (protein kinase M) maintains long-term memory.”

But he said the plan is to find out.