YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon “”mdash; Gabriel Meng keeps a box of old photos, programs and memorabilia tucked away in his room. The box doesn’t often see the light of day; it is a sacred safe that protects and preserves the memory of Meng’s youngest son, “Papy.”

“I had so many goals for him,” Meng says trailing off.

Meng lost his son in the most unconventional of ways in 2008.

America was supposed to be the land of opportunity, the place where Papy would thrive, develop into an NBA star, get a doctorate and someday become a banker. Papy watched over his neighborhood in Yaoundé, always the one to step in and stop a fight. That’s how Menghe a’Nyam got his nickname: “Papy” ““ “Papa.”

All of a’Nyam’s admirers back home were watching him play in a scrimmage on satellite television, when, as he was running down the court, he fell to the hardwood and died.

However, Meng had not been watching this particular game, making him the last person in town to discover his son had died.

He got a phone call from a’Nyam’s college, Adelphi University in Long Island, New York, two full days after his son’s heart stopped beating.

The man told Meng in English: “Papy is dead.”

“And that,” Meng said, “was the last word I understood.”

Paul Homoie Ntang Mpie is perhaps the only person in Cameroon who can relate to Meng. His son Guy Alang-Ntang also died suddenly, and in exactly the same way.

Ntang’s son made a habit of calling his father at midnight. Coincidently, Ntang’s phone rang around that time on April 16, 2007. But instead of hearing his son, he heard a woman’s voice on the other line. She spoke French and introduced herself as the school’s French professor. It took the tactful woman several minutes to get to the point, but as soon as she did, Ntang calmly switched off the phone.

Thirty minutes later, Ntang’s wife began to wonder why she hadn’t yet been called to talk to Alang-Ntang. But when she found her husband, he wasn’t on the phone with her son.

He was crying in the corner, alone.

“We can’t go a day without thinking of him,” Ntang said softly. “He loved everyone.”

A “problem for sports doctors”

Until the summer of 2010, the families of both a’Nyam and Alang-Ntang remained unclear about what caused their sons’ sudden deaths. One of a’Nyam’s brothers believed that a’Nyam’s passing was part of an American conspiracy that was never to be revealed to his family. Meng remained frustrated that he was left without answers.

“The autopsy doesn’t say anything,” Meng said. “It just says that Papy died. Not the reason.”

The Daily Bruin obtained the official cause of death for Alang-Ntang, who died in the state of New Hampshire, but was unable to obtain records pertaining to a’Nyam because of New York State law.

Dr. Thomas Andrew performed the autopsy on Alang-Ntang and remembers the case specifically because of the rare condition he found.

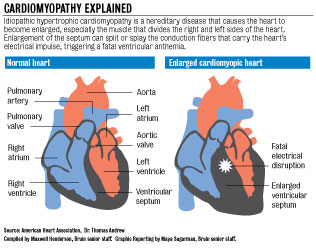

Andrew determined Alang-Ntang’s cause of death to be cardiomyopathy. According to Andrew, the rare disease causes the heart muscle to become unusually thickened and enlarged. This makes the heart unstable and prone to “an electrical short-circuiting” that can trigger a fatal irregular heartbeat.

Alang-Ntang is not the only African athlete to have died from cardiomyopathy. In 2006, Kenie Freeman, a basketball player from Nigeria, died of the same disease. And in another more famous example, Cameroon midfielder Marc-Vivien Foe collapsed in the middle of a Confederation Cup match in 2003 because of heart failure.

When told about cardiomyopathy, both Alang-Ntang’s and a’Nyam’s families recognized the problem and recalled other community members who died of similar heart conditions.

A report authored by Karen Sliwa and colleagues calls cardiomyopathy an “endemic in Africa.”

Andrew confirmed that the disease appears to be genetic. And though he cautioned that no study has linked the disease to athletes, he said that increased cardiovascular activity would likely exasperate the instability of a pathologically enlarged heart.

“This is an ongoing problem for sports doctors,” Andrew said. “If you know a kid has an enlarged heart, whether or not you know what the specific cause of that enlargement is, do you restrict them or do you not restrict them? It’s a hard call to make.”

Leaving home

Basketball led a’Nyam and Alang-Ntang to the United States, and they never made it back home. But before they ever got to New Hampshire, they left an indelible mark on Yaoundé.

As his mother’s last and youngest child, a’Nyam developed a soft heart and gentle manner that shown through his tough muscular frame. The big boy curled up next to his mother at bedtime for as long as he lived in her home.

But despite his warm demeanor, a’Nyam held a fire inside him that drove him toward perfection. He was determined to be the best at everything. In one case, that meant finishing and winning a race even after his pants fell off in the first 50 meters.

Everyone knew that one day a’Nyam would get his chance to play abroad.

Alang-Ntang was only 6 years old when he first informed his family that he planned to travel to America one day. The matter was as good as settled in his head. He loved American music, particularly James Brown, but Michael Jordan was his true obsession. This made it easy for Alang-Ntang to choose his jersey number when he did in fact arrive in Indiana.

Like a’Nyam, Alang-Ntang steamrolled through tasks, making sure each was done before moving to the next, always asking how he could help the family.

He would routinely assure his mother that one day, when he was famous, “people will talk about you.”

When his family finally saw Alang-Ntang off at the airport, they sent with him his personal Bible, his chaplet and a picture of his mother.

All of that was boxed up by Karen Saunders, a family friend, and sent back with a big bag of basketball shoes that Alang-Ntang had meant to take home with him on his first trip back to Yaoundé. The trip was scheduled for December 2007, but the box arrived seven months earlier than planned.

Memorials across an ocean

The deaths of a’Nyam and Alang-Ntang struck a blow to two separate communities thousands of miles away, simultaneously.

At the New Hampton School, Alang-Ntang had gained a reputation as the man whose laugh you could hear from miles away and whose smile radiated from just as far.

According to reports, Alang-Ntang was in the middle of a pickup game on a Monday night, and as he backpedaled down the court, he fell and never got back up.

His basketball coach Jamie Arsenault remembers that pickup game like it was yesterday. Alang-Ntang was playing “unbelievably,” perhaps because Gregg Marshall, the newly appointed Wichita State basketball coach was in the gym watching his recruit.

“I still don’t believe any of it,” Arsenault said. “I still think they (Alang-Ntang and a’Nyam) are off at college, and I’m waiting for them to come back.”

Saunders, a mother of two who had grown close to Alang-Ntang over breaks that he spent with her family, was the hardest hit by the news.

“I was shocked,” she said. “Guy of all people, I mean he was just the most alive, boisterous, loud, funny. … Nobody could believe it.”

It was Saunders who would serve as the link between Alang-Ntang’s community at New Hampton and his family back in Yaoundé. Alang-Ntang’s brother Serge Borgia Bontsebe Ntang said that Saunders was the only person his family kept in touch with during the ordeal. She provided them with all the details about the memorial service planned at the school and the burial.

“It was like we were there with her,” Bontsebe said. “We wanted to go, but it was really hard. So we asked Karen to be his mother, to be like we were there, to do what we would do.”

Back at home, the community remained in a state of disbelief.

Alang-Ntang’s death was so sudden, and they did not understand. While reporters and doctors scratched their heads, family members in Cameroon mourned, still unsure of how this could have happened.

It took the ocular proof of people gathering for Alang-Ntang’s burial to make the truth hit home Alang-Ntang’s sister Josephine Stephanie Ntang.

“I was always telling myself, “˜It’s not true, it’s not true.’ I didn’t believe it until I went to the village and realized that they were holding a memorial for him. I fell unconscious. Then when I saw everyone, I realized, it’s true, it must have happened,” she said.

And with that, she shuddered, rose and left the room.

The news of a’Nyam’s death spread in a similar fashion. When a’Nyam died on June 29, 2008, he was a year removed from his own time at New Hampton and attending Adelphi University in Long Island, New York. A memorial was held both in the United States and back home in Yaoundé, and once again, the family largely remained in the dark as to their son’s cause of death.

No one felt more pain than a’Nyam’s mother.

In Cameroonian culture, the last child holds a special and almost preferential place in his parents’ eyes because he is the last of a long line of children. After him, there will be no more. Thus the baby of the family gets all the affection, and he carries with him the weight of being the family’s last hope.

For these reasons, Don Jeannette Meng still, literally cannot speak about the death of her son. Though she listened intently while her husband recalled a’Nyam’s life, she interjected only twice in two hours.

When a’Nyam’s father was asked about how difficult it must have been to lose a son, a’Nyam’s mother, in an almost pleading voice said, “It was difficult for me.” And when Meng was asked if he would choose to send his son abroad if he could do it all over again, his wife cut in.

“The mother says no.”

Meng smiled. “The mother says no, the father says yes.”

Fulfilling destiny

The hypothetical question posed to a’Nyam’s parents may soon become a question of real significance to Alang-Ntang’s family.

Alang-Ntang’s younger brother, Noel Mpie Ntang Jr. is 17 years old and wants to follow in the footsteps of his brother.

“When I was a little boy I didn’t know that I would play basketball,” he said. “It was after the death of my brother that I realized I could play, and I had the skills. I heard I was a good player, and I want to go to the United States and continue the work of my brother.”

Armed now with the knowledge of the genetic nature of Alang-Ntang’s disease, Ntang, like Meng, didn’t hesitate when asked about his youngest son’s future.

“If I had to do it again,” he said, “I think I would do it again. Because nobody knows what will happen or what tomorrow will bring. Everybody has his own destiny.”