After the discovery of a polyp in her colon in 2001, Pamela Sakuda underwent numerous biopsies and a surgery only to receive news she had stage four, metastatic colon cancer.

The diagnosis contrasted with the 54-year-old’s healthy and active lifestyle, as Sakuda and her husband Norbert Litzinger followed a vegan diet and exercised regularly.

Regardless, Sakuda was given six to 14 months to live, and she started aggressive chemotherapy.

But even after the 14-month window, Sakuda was still alive. As time continued to pass, she started to feel the stress of the unknown.

“When things didn’t go the way medicine said it would, Pam naturally got depressed,” Litzinger said.

To help with her depression, Sakuda was placed on antidepressants. But the couple’s busy lifestyle came to a halt ”“ they stopped buying concert tickets because they were unsure if Sakuda would still be alive to see the show.

Instead of making plans months in advance, the couple would only look ahead a day in advance.

“We stopped living,” Litzinger said. “It’s a crushing psychological weight … that’s what Pam was really starting to feel.”

So when Litzinger saw an advertisement in 2005 for a psilocybin study at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance that was geared towards terminally ill cancer patients with anxiety, he and his wife decided to give it a try, knowing they had nothing to lose.

The study was conducted by Dr. Charles Grob, chief of the child psychiatry department at Harbor-UCLA and a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences.

After studying research from the 1950s and 60s on the effect of hallucinogenic drugs for anxiety, Grob said he hoped to establish feasibility and safety in hallucinogenic treatment of the same condition in cancer patients.

Research was halted 40 years ago because of the cultural stigma of the substances. Nevertheless, Grob said he felt enough time had passed to reevaluate the past trials and conduct more rigorous research.

He then created a protocol that was approved by Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, the Food and Drug Association and the Research Advisory Panel in California, among other organizations.

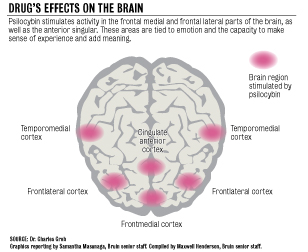

But instead of using LSD, as in many of the trials from the 1960s, Grob chose to use psilocybin, the main ingredient in hallucinogenic mushrooms, based on its shorter acting experience, milder and more controllable after effect, stronger visionary inducement, and its decreased chances of causing paranoia, he said.

To receive treatment, patients would go into a room decorated with flowers and cloth wall hangings, which were intended to create a more comfortable and pleasant environment, Grob said.

At the end of the six-hour session, patients discussed their psychological experiences. Patients received one more additional treatment and then went back for follow-up visits and discussions for six months, according to an article Grob published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in early September.

After compiling the data, Grob found there were no adverse physiological or psychological effects from psilocybin, such as paranoia or increased anxiety.

The study also indicated an improvement of mood in patients.

After treatment, patients were also able to transcend states of consciousness to discuss topics like close relationships with family and friends, and how their disease affected their lives.

“Hallucinogens offer potential for new treatment models for conditions that are not as responsive to conventional treatments,” Grob said, adding that the study indicated the feasibility of receiving funding and conducting such a trial.

“There’s certainly strong indication for further research in the field.”

But the limiting factor for further research is funding. While Grob received financial backing from the Heffter Research Institute, a private organization that supports research on psychedelic drugs, federal funding for such trials may take more time, said Dr. George Greer, medical director of the institute.

As two additional studies on psilocybin treatment for anxiety in cancer patients are ongoing at New York University and Johns Hopkins University, Greer said he hoped the results would justify a grant from the National Institutes of Health for a larger study.

“Our ultimate goal is … for the FDA to approve psilocybin for this use, for cancer patients anywhere,” Greer said. “There is something real happening here that can really help people.”

For Sakuda, the combination of the medication and the therapeutic psychological sessions during the Harbor-UCLA study helped her realize she had allowed her fear of the future to destroy her present, Litzinger said.

As a result, the couple started to go out again. Together, Litzinger and Sakuda hiked around San Francisco, went clubbing, and made long-term plans for the months ahead, Litzinger said.

Sakuda lived for 22 months after the psilocybin treatment ended and died at home on Nov. 10, 2006.

“(The treatment) made the last two years of her life very meaningful, just periods of great, great joy,” Litzinger said. “I’m not sure she would have lived as long without it.”