Eva Hesse, dead at 34, lives again.

Although the artist of German origin died in 1970 of a brain tumor, her ghost is currently on display at the Hammer Museum in a phantasmagoric collection of early paintings from 1960. As far as records show, Hesse never gave names to the 19 works in the collection, which is touring the nation under the title “Spectres 1960.”

“It is a term that defines these paintings very well,” said Allegra Pesenti, curator of the Hammer’s Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. “They’re not literal portraits or self-portraits. They’re sort of ghosts of portraits. There’s a sense of phantasm … but then also this sense of a soul of the artist that’s coming through.”

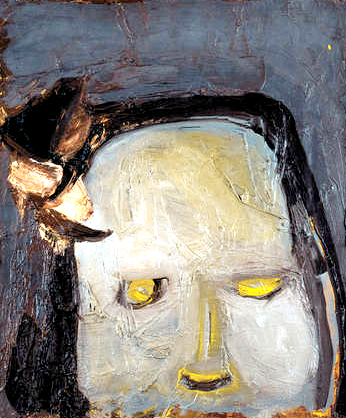

Layers of earthy tones smear the canvas in broad brushstrokes to form ghostly apparitions. The shape of the figures is undeniably human, but Hesse’s technique, like a late-night séance, draws out the tableaux’s dormant spirits: fragile, anguished and self-searching.

“You see a use of figuration that is complicated and intriguing and haunting all at the same time,” said Sarah Stifler, director of communications at the Hammer Museum.

Hesse’s paintings are complex because they are so personal. This revealing intimacy is a deviation from her later abstract sculptures for which she gained celebrity among artists and the label of a post-minimalist by many art historians.

“Eva Hesse did sculpture that was often called post-minimalist,” said Douglas Fogle, the Hammer’s chief curator. “These paintings are not a part of that body of work; they’re earlier. They’re very much rooted in the history of painting from the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s, but they’re not part of this larger thing that she became known for, which is sculpture in the post-minimalist way.”

Although the paintings speak for themselves, Hesse’s own diary entries illuminate their contextual significance in the artist’s life and creative development.

These portraits depict a fragile emotional state: one of a young artist coming out of school into the wide world and standing in front of a blank canvas. Having recently finished her graduate art studies at Yale, these paintings are a form of self-examination and an artist putting herself to the test, Pesenti said.

The collection is divided into two main groups.

The majority of the paintings are a mixture of large and small tableaux, depicting two spectral figures. A small group of larger frontal portraits comprises the rest of the collection.

“Consider (the paintings) as works she was making for herself. The works with two figures, you’ll notice that there’s often a bringing together, but also a stretching apart … the figures are kind of stretching to the side of the edge of the Masonite,” Pesenti said. “Is it herself and the ghost of herself? Some writers have claimed that this is Eva thinking about her family and the impression of herself in the world.”

This same fantastic gravity that pushes as it pulls is equally apparent in the frontal portraits. A similar color palette of bog green and peat gray forms a ghostly outline of the artist; the wraith-like, ragged bodies belie crimson lips and flecks of hot pink, vestiges of Hesse’s independent vivacity.

“You have to consider Eva as a female artist in a very male-dominated art world in New York at the time. I see these paintings very much as a self-discovery, a self-examination,” Pesenti said. “She claims in her diary at this point in 1960 that she wants to be independent of what she sees around her. … That she doesn’t want to be influenced by the commentaries from the exterior, that she really needs to paint herself out.”

The 19 paintings share the four rose-tinged walls of a single room. Compared to the spatially expansive Mark Manders exhibit with which Hesse’s work shares the same wing, “Spectres” is a much more intimate, almost reverent experience.

“The Eva Hesse show is a smaller show, so it’s just a smaller space. … If you gave Eva another 600 square feet of space there’d just be a lot of white wall between (the paintings),” Fogle said. “The Eva Hesse works need to be together. They like to bounce off each other.”

According to Stifler, Hesse is one of the top five sculptors of the 20th century.

“Spectres” is an opportunity to examine a collection of incredibly accomplished paintings in which the body is both subject and object, a style which attempts to leave the two-dimensional surface.

Similarly, these paintings, unwanted and relegated to storage space, are finally coming out of darkness and finding their own independence.