When I was young, carefree and in a Southern Baptist School, there was no finer pleasure than in stealing glimpses at the books banned by The Powers That Be. From the covertly Satanic (a Harry Potter novel) to the clumsily Darwinian (a Pokemon comic), forbidden fruit never tasted so sweet as behind the backs of teachers hostile to all things fun and worth reading. I recall one lesson wherein I learned my first bad metaphor: forbidden knowledge is a bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos ““ eat it and burn. But oh, it burned so good.

Those days are gone now; to a mind spoiled by university, the idea of banning books beggars belief. But let us not get ahead of ourselves. Libraries across the nation have declared this week “Banned Books Week” (the 28th annual, in point of fact), to honor and defend something sadly still endangered. I’m talking about free expression in general, and it’s something we’d all do well to cherish. As much as we’d like to believe that we love free speech, this week is a fitting time to assess just how true that is.

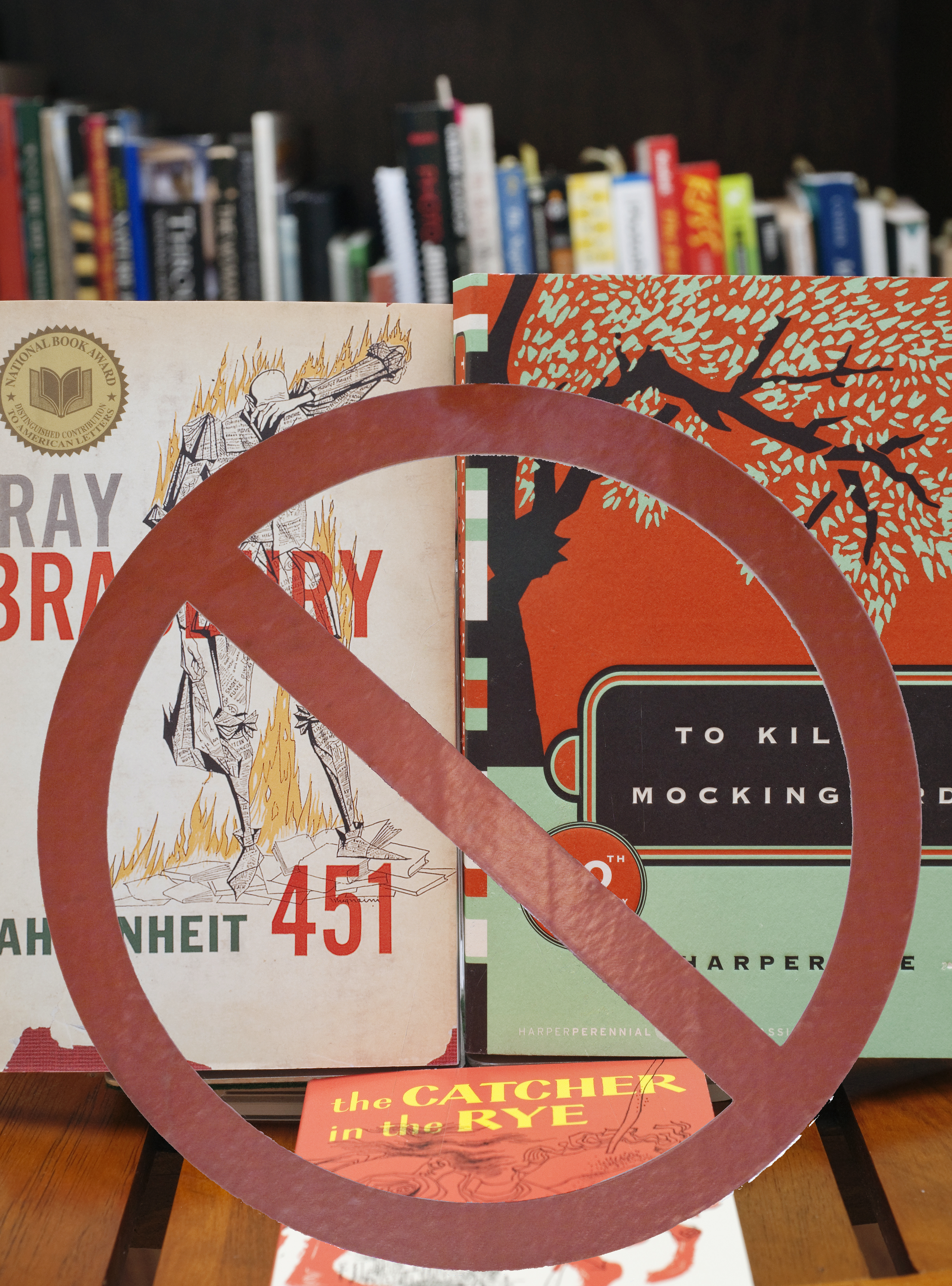

Our library, at least, boasts a noble track record of defending that liberty. The Moore in Moore v. Younger (the 1976 case which helped to end library censorship) was none other than our very own Everett T. Moore, former UCLA Librarian. And who can forget that adorable anecdote of Ray Bradbury slaving away in the basement of Powell Library, writing the anti-censorship polemic, “Fahrenheit 451″?

But enough self-congratulating. There is more to free speech than letting “Mein Kampf” occupy some shelf space. Perhaps Deborah Caldwell-Stone, deputy director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, said it best: “Many people do not understand what the First Amendment really means.”

When I spoke with her about Banned Books Week (which her office sponsors), our conversation largely focused on a familiar theme ““ children being barred from sex, science and other paperbound heresies. Yet a wider-reaching thread weaves itself across this week, a subtler threat to speech. It is the very attitude of our culture: what she described as “an impulse to censor what people disagree with or don’t understand.”

How many times this year have I heard the complaint, “Freedom of speech does not include insulting X?” Too many times, I’m afraid. If I recall, this publication ran a couple columns along those lines. Appeals to “sensitivity” and “respect” were often waved around like they had anything to do with free speech. And then there’s my favorite cop-out: “Of course you have the right to say so but you still shouldn’t.”

To return to Bradbury’s famous dystopia, we must remember that censorship begins not with the vulgar, the offensive or the utterly stupid. It begins with the safe, the sterile and the oh-so-sensitive.

We students dwell, of course, in a magical bubble of relative freedom of expression. Braving the hillside swarm up Bruin Walk, I spy a “Repent or burn in hell: Jesus loves you” sign-wielder opposite the lonely secularists’ table, and if I’m lucky I’ll catch the disgruntled gentleman ranting about physics, capitalism and God knows what else. We are of the age, thankfully, that adults no longer dictate the idiocies we subscribe to.

Yet the temptation to censor remains. Every time someone calls foul on a statement for the sake of sensitivity, we take a collective step backward. Every time we withhold our tongues to spare someone’s feelings, we reinforce the necessity of a week like this ”“ to remind us of the slippery slope to censorship.

Let us not be like Terry Jones, who would waste perfectly good paper to make a bootless point. Nor should we be like those who doused his flame, silencing a statement to appease the easily offended (or worse, the eagerly violent).

Let us instead, like the adults we think we are, welcome stupidity, vulgarity and insolence, if only for the smug glee of knowing that we’re not afraid of words.

This week, nothing is sacred. The books, the words, the thoughts we fear or loathe the most are the very ones worth protecting ““ and inspecting now. For if there is one thing a taboo is good for, it is to be broken.

Are we closer to censorship than we think are? E-mail Manalastas at jmanalastas@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to opinion@media.ucla.edu.