They say home is where the heart is.

But politicians’ pretty words won’t address homelessness in Los Angeles.

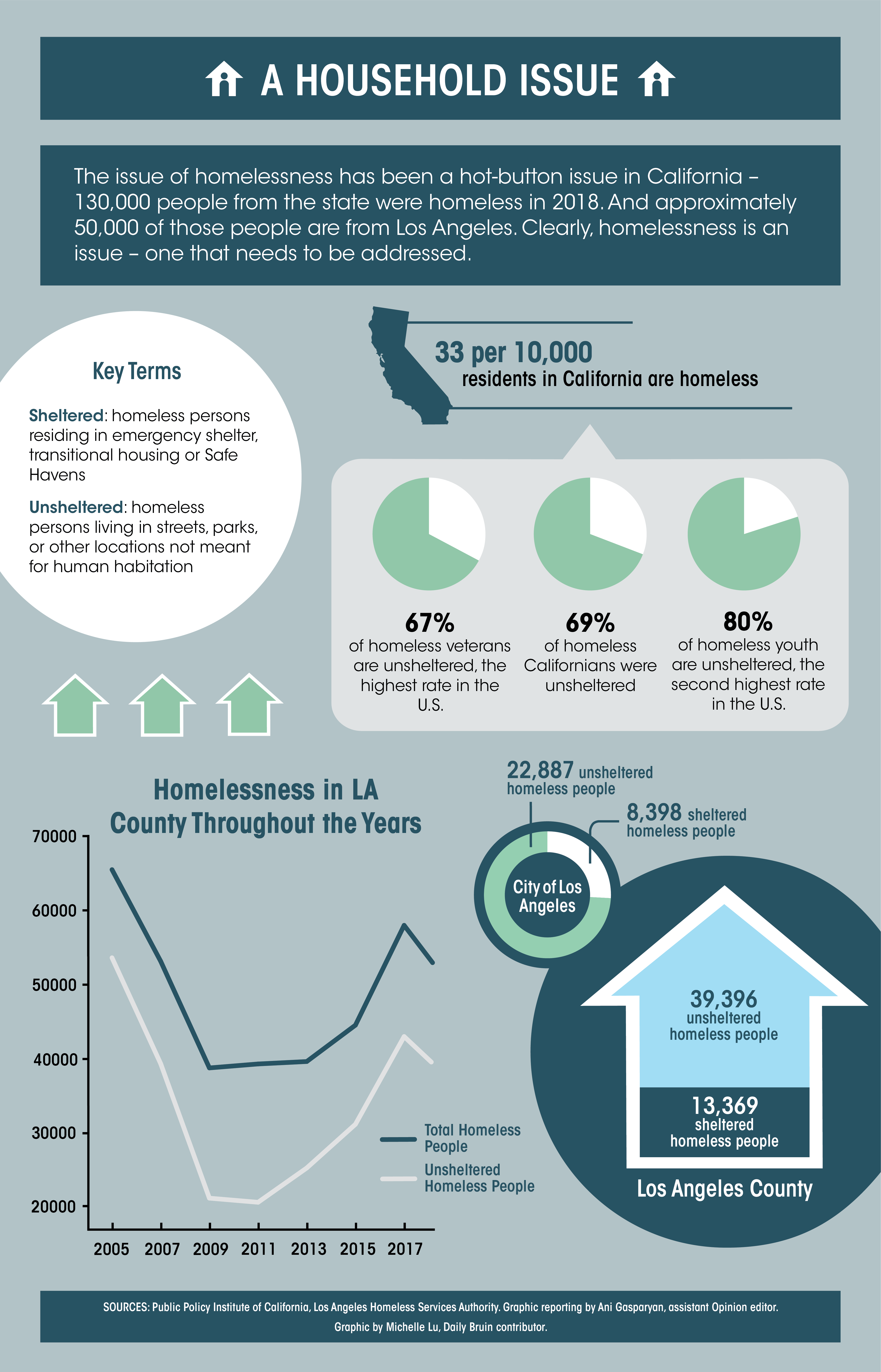

California alone has the highest homeless population in the U.S. In LA County alone, the homeless population is roughly 58,000 – and growing. In fact, LA hosts the largest homeless population in the state.

California leaders like Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Congressman Ted Lieu have tried to address this by drafting a bipartisan bill called the “Fighting Homelessness Through Services and Housing Act” to grant $750 million to local governments for skills training, substance abuse treatment, mental health care and family care services.

But in the local purview, solving homelessness has become a publicity stunt to clean streets through short-term solutions. No matter how promising the bill’s provisions are at the federal level, they won’t be accessible here in LA, where antiquated local practices discriminate against homeless individuals. Local politicians enforce policies that lead to the displacement and increased criminalization of the homeless, not the compassionate approach they use in their rhetoric. This municipal system renders the federal bill moot in helping LA’s homeless individuals.

Throwing money at the problem clearly doesn’t work. The last city budget approved $30 million to address public health concerns about the living conditions found inside homeless encampments. That money is not going toward housing stability or food provisions. Instead, officials have taken to kicking homeless individuals out of their communities so sanitation workers can power-wash the streets.

Homeless people only get 24 hours’ notice before sanitation workers and local law enforcement arrive. Often, the postings are barely visible and can even be placed right as a sweep starts. Unattended personal belongings are tossed into the trash or confiscated by the city – even tents, food or personal documents that could have been used to apply for housing, jobs or welfare.

“If the intention was to actually clean the streets, they could add bathrooms in Skid Row or pick up trash, but they don’t,” said Gary Blasi, a UCLA law professor emeritus. “The larger intent is to respond to complaints about homeless encampments.”

These quick fixes make for sparkly streets, but leave officials’ hands dirty. Sanitation sweeps aren’t helping the victims of homelessness access public health or housing. Instead, they make the city look better, while homeless individuals suffer possibly permanent consequences.

And this practice isn’t new. Municipal codes are weaponized against homeless people for circumstances out of their control, like sleeping on benches, streets or sidewalks. They’re intended to maintain public order, but are used as a justification to continue pushing homeless people out of the public eye.

A Million Dollar Hoods report found that the proportion of homeless arrests has increased, the predominant charge being failure to appear in court. And none of the top five charges for these rising homeless arrests were for violent crimes.

Ashraf Beshay, a North Westwood Neighborhood Council member and part of the Homelessness Task Force in Westwood, said he often sees this issue hitting close to home.

“They’ll have to deal with jail time, which goes on their records,” Beshay said. “It feeds into a cycle of poverty, leading the homeless into incarceration.”

And despite lawsuits in the past, police haven’t stopped targeting homeless individuals. LA was sued in 2003 for unconstitutionally enforcing an overnight sidewalk sleeping ban, and the court ruled that punishing people for circumstances beyond their control violates the Eighth Amendment.

However, there are hundreds of other citations that continue to be used against them beyond the ones delegitimized by the court case. These archaic and repulsive municipal codes need to be reformed before we can think about funding initiatives to address homelessness.

“If you don’t have political will, it’s just money that’s going to be sitting around,” said Kienna Qin, a second-year statistics student and advocacy director for the Hunger Project at UCLA. “That’s what happened with Measure HHH, and not much came out of it.”

That’s not to say the city hasn’t tried. Mayor Eric Garcetti has pushed for housing projects, including Proposition HHH and “A Bridge Home,” both of which aim to build permanent and temporary supportive housing units. Yet by the end of 2018, not a single housing unit was built by Proposition HHH. And the fine print of the “Bridge” housing policies allocates more money for increased police presence and sanitation sweeps than it does for the construction of housing units.

So no matter the amount, it’s hard to believe federal aid will finally solve LA’s homelessness when municipal codes and sweeps would inevitably block the benefits of any helpful legislation.

Local politicians can say what they want – but it’s clear this city’s heart and home aren’t open to homeless individuals.