This post was updated April 21 at 5:00 p.m.

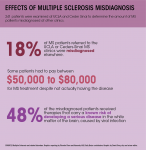

UCLA researchers found almost one in five multiple sclerosis patients referred to UCLA Ronald Reagan Medical Center or Cedars-Sinai Medical Center were misdiagnosed with the disease.

Marwa Kaisey and Nancy Sicotte, lead investigators of the study, studied a sample of 241 patients to find how many patients within that pool were misdiagnosed and to determine the root of the misdiagnoses. The study will be published in an academic journal, Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, in May.

Among those misdiagnosed, 72% had been prescribed MS treatments, according to the study. Forty-eight percent of these patients received therapies that increase the risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a serious disease in the white matter of the brain.

Multiple sclerosis, a disease in which the immune system attacks one’s nerve cells, is notoriously difficult to diagnose. Kaisey, a Cedars-Sinai physician who specializes in multiple sclerosis and neuroimmunology, said there is no definitive test to confirm multiple sclerosis.

“In multiple sclerosis, there is no single test that says ‘Yes, you have it,’ or ‘No, you don’t,’” Kaisey said. “We use diagnostic criteria that include a clinical symptom like loss of vision or weakness in arm and leg. The second step is to do a brain MRI.”

Despite the existence of formal diagnostic criteria, not all physicians employ these in the same way, Kaisey said.

“There are strict criteria but not everyone adheres to (them),” Kaisey said. “I strongly believe we need better tools that take some of the subjectivity out of it and make it less time-consuming.”

Sicotte, who is also interim chair of the Cedars-Sinai department of neurology, said changing diagnostic criteria could have contributed to the increased misdiagnosis rate.

“It used to be you had to have two clinical events in order to have a diagnosis, but now we use MRIs to help us make the diagnosis early,” Sicotte said. “A lot of the cases that we saw that were misdiagnosed were because people were sort of taking shortcuts.”

Kaisey said migraines were the most common condition misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis.

“Migraines can cause neurological symptoms and white spots on brain MRIs,” Kaisey said. “The most common diagnosis to get confused with multiple sclerosis is migraines.”

Barbara Giesser, a co-author of the study and clinical director for UCLA’s multiple sclerosis program, said their study builds on previous research on multiple sclerosis misdiagnoses by also calculating the costs and risks associated with the issue.

“Seventy-two percent of people … had been misdiagnosed for a disease-modifying therapy, and we calculated the cost of their therapy,” Giesser said. “These agents are expensive, and they have potential side effects.”

Sicotte said the cost of treating a misdiagnosed case can range from $50,000 to $80,000 per year for a patient. Even though insurance may alleviate some financial burden for patients, this cost still affects the healthcare system.

“Not just one individual will have to pay, but somebody’s got to pay,” Sicotte said.

Kaisey said she thinks patients may feel most upset about losing a part of their identity in the case of a misdiagnosis.

“(Multiple sclerosis) has become a small part of (the patient’s) identity, like joining multiple sclerosis support groups. People make plans around multiple sclerosis,” Kaisey said. “To reverse that is very, very difficult.”

Patients may also be frustrated by their exposure to potential negative side effects of unnecessary treatment, Sicotte said. Some treatment methods, such as injections, can be painful and possibly result in infection.

“The biggest thing we worry about with multiple sclerosis treatment, given that they all affect the immune system, is infection,” Kaisey said. “They are generally safe, but they all have their pros and cons.”

Kaisey said it is important to develop easy-to-use, accurate diagnostic tools for the future. Sicotte said Cedars-Sinai physicians are developing a new imaging technique called central vein sign that will allow them to distinguish multiple sclerosis from other conditions, such as migraines.

Kaisey also recommended patients visit a multiple sclerosis specialist to get a more detailed diagnosis and ask questions about treatment options.

“Multiple sclerosis specialists are few and far between, so patients are dealing with general neurologists,” Kaisey said. “It would be worthwhile to see (a multiple sclerosis) specialist.”