Eric Scerri, a UCLA chemistry lecturer, has written at least six books discussing the orientation of the periodic table.

His office is cluttered with posters and three-dimensional models of different periodic systems. Even his credit card has a picture of the traditional periodic table.

“The periodic table has been called the paradigm of chemistry; it’s the framework, it simplifies and organizes chemistry,” he said.

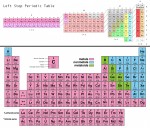

The periodic table was created 150 years ago by Dmitri Mendeleev, but is still a point of contention for many researchers in the field of chemistry. Since then, the table has been published in at least a thousand different forms, organizing the elements in different shapes and using different criteria, such as atomic weight and number of orbitals.

The placement of helium is at the center of the periodic table debate. The periodic table traditionally taught in textbooks, which organizes elements based on chemical traits such as reactivity, places helium in the rightmost column with the other less reactive elements.

The left step table, one of the many proposed alternatives to the traditional table, prefers to organize elements based on the number of outermost electrons regardless of reactivity and groups helium with highly reactive elements such as magnesium and calcium. This organization makes sense for physicists who think of elements in terms of orbitals and electrons. For chemists, however, placing helium with highly reactive elements feels wrong.

“From a purely chemistry point of view, this version seems to be a bit unnatural and forced,” Scerri said. “This highlights the tension between physics and chemistry.”

Philip Stewart, a chemistry professor at the University of Oxford, said he likes the aesthetic appeal of organizing the elements in a spiral.

“Curves appeal to our eyes, which evolved for millions of years,” he said. “In a world of curved forms, straight lines and right angles only appeared with the invention of building with blocks or bricks a few thousand years ago.”

While the spiral might look nice, it does not break the elements into periods so, if he had to choose, Stewart said he would pick the left step table.

He said he initially resisted the idea of putting helium with alkali metals such as magnesium and calcium because of their varying reactivity, but said this difference might be insignificant because the purpose of the table is to understand electron configurations.

He said there are rare situations in which an element’s electrons do not behave as expected according to their chemical traits, suggesting the element should be grouped with other elements that share the same electron configurations but not the same chemical traits, which do not always align. The easiest way to resolve this is to put a small symbol at the corner of the odd elements, indicating they are exceptions.

René Vernon, an Australian-based periodic table researcher, said he values clarity in a periodic table more than aesthetic appeal.

He said his main concern with the left step table was that it does not show the progression from metals to nonmetals and other chemical trends across elements.

“The left step table appeals to a lot of people based on its aesthetics, it’s highly regular, it’s highly ordered,” he said. “It’s a very interesting form to study but it’s at the expense of clarity.”

Vernon said three-dimensional versions of the periodic table have their own merits and demerits but can be difficult to convey in a textbook. Scerri said there are people trying to create three-dimensional pop-up tables in textbooks.

“The big question is ‘How efficiently is information conveyed and what is it representing?’” Vernon said.