Researchers in the UCLA Congo Basin Institute and Center for Tropical Research are using genomic tools to track down the global trafficking routes of pangolins and their scales.

Ryan Harrigan, an ecology and evolutionary biology professor and researcher in the Pangolin Trafficking Project, said pangolins are severely endangered due to poaching for their scales, which are believed to have medicinal qualities in traditional Chinese medicine. He added researchers are studying the genetic variances among species of pangolins across the globe to distinguish where and which population they came from.

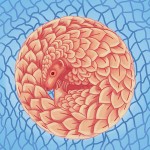

“When pangolins get scared, they roll up into a little ball and don’t move, making them really easy for hunters to collect into bags,” Harrigan said.

Since fall 2017, Harrigan said researchers at UCLA have begun collaborating with researchers at the Congo Basin Institute, a foreign affiliate of UCLA in Cameroon, as well as in the University of Hong Kong to prepare for obtaining genetic samples from pangolins next summer.

The eight species of pangolins are native to rainforests in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa and play an important role in maintaining the rainforest ecosystem, such as in dispersing seeds from their omnivorous diet, Harrigan said. Trafficking pangolins is illegal internationally, and confiscation of pangolin scales at ports are becoming more common around the world, not only in Asian and African ports.

“There was a huge seizure in 2017 of pangolin scales in the Netherlands, so clearly the traffickers are onto the fact that certain ports are being checked,” Harrigan said. “This is an effort by traffickers trying to bypass the laws.”

In order to accurately map out trafficking routes, Harrigan mentioned he and other researchers will be comparing the genomic data of trafficked scales and native pangolins to trace back what regions the scales of pangolins are originally from.

Various species of pangolins are spread across different countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and have small genetic differences as well, Harrigan added. These genetic differences will allow researchers to distinguish which region or country the trafficked pangolin was captured from, as well as pinpoint certain heavily trafficked populatons, to a certain country.

Thomas Smith, a professor in ecology and evolutionary biology who is directing the project, said he and other researchers plan to travel to the Congo Basin Institute to obtain DNA samples of pangolins from different regions of Africa.

Although samples from live pangolins are ideal, they can also come from pangolins sold in roadside markets. Smith added it may be possible to obtain DNA samples from the Chinese medicine products made from pangolin scales. Currently, they are working on obtaining permits to sample pangolins in the summer, Smith said.

While some people in the United Kingdom and Hong Kong are aware of pangolin trafficking, Smith said that the general public in the U.S. is not familiar with the issue.

“Pangolins are the most trafficked mammal worldwide that no one’s ever really heard about,” Harrigan said. “A lot of the time when I tell people I’m studying pangolins, they say, ‘penguins?’”

Raising global public awareness is crucial to increase funding and research to mitigate pangolin trafficking, Smith said. He added criminal cartels involved in trafficking have also caught the attention of the U.S. government, as money gained from the pangolin trade has been used for activities such as drug and weapon purchases.

Kevin Njabo, an assistant adjunct professor at the Institute of Environment and Sustainability and Africa director of the UCLA Center for Tropical Research, said pangolins are a familiar sight for locals in his home country, Cameroon.

“The species of white-bellied pangolins are found everywhere in the forest. If you’re from that region, you’ve encountered them at least once in your life,” he said. “But we’ve noticed a reduction in numbers.”

Njabo added locals are not often aware of illegal pangolin trafficking and at times rely on them as a food source. Educating and engaging local people to protect pangolins is a crucial part of conserving the species.

“I think the biggest hurdle is raising public awareness,” Harrigan said. “If you look up a picture of a pangolin, they’re the cutest things ever, close to kittens in terms of cuteness. I hope local people start to take some pride in pangolins and try to preserve them.”