Throwback Thursdays are our chance to reflect on past events on or near campus and relate them to the present day. Each week, we showcase and analyze an old article from the Daily Bruin archives in an effort to chronicle the campus’ history.

If you’ve ever felt UCLA Housing’s late-night access control procedures were overkill, you’re not alone. UCLA thought the same thing in the 1980s.

Access control wasn’t as extensive back in the day, and the ramifications were telling. In 1987, two people entered a first-year student’s Rieber Hall dorm room via an unlocked door and raped her. Residents reported seeing the student’s two attackers wandering the dorm corridors between midnight and 6 a.m. The student sued the university for neglecting to implement safety measures and creating a dangerous environment for students living on campus.

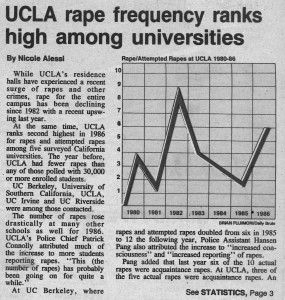

Bruins were rightly concerned about campus safety. The campus had been seeing a notable number of attempted sexual assaults and actual sexual assaults at the time. A Daily Bruin story published Feb. 11, 1987, reported there was a sudden increase in the number of rapes and attempted rapes on campus in 1986 – six that year, which was up four from the year prior. The Bruin also reported UCLA was ranked the second-highest among five UC campuses in 1986 for rapes and attempted rapes.

Students consequently pushed the administration to beef up security at university dorms. Access control hours were extended, photo identification was required of those trying to enter dorm corridors and a more comprehensive guest pass procedure was added.

UCLA also had to cough up for its subpar housing security. The Daily Bruin reported UCLA had eventually settled for $300,000 – what amounts to about $584,000 in 2018 – with the student who was raped in 1987. The university had initially offered only $100,000, or about $200,000 in today’s terms, as a settlement amount – a miniscule amount compared to the millions of dollars companies like Fox have paid for sexual harassment legal settlements. The settlement amount was part of more than $500,000 the university spent – about $970,000 in today’s terms – in investigating and settling the case.

The university also received a bit of rough publicity at the time for its lack of transparency. The Daily Bruin reported the American Civil Liberties Union sued on the paper’s behalf to force the university to disclose documents regarding the 1987 rape after it had failed to do so upon initial request. Public institutions such as universities are required by the California Public Records Act to disclose documents to parties who request information about matters of public interest, such as sexual harassment and assault cases and settlements.

The Daily Bruin also got hold of hundreds of other documents about the university’s handling of other sexual assault and harassment cases. The Washington Post reported on the Daily Bruin’s findings at the time, stating UCLA paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in settlements for these cases.

Naturally, UCLA wasn’t all that receptive to the attention and demands it was getting. The university was of the opinion that upping security would turn the residential area into a military complex of sorts.

“The general theory was that the security or lack of security permitted the rapist to get into the building,” said Alan Zuckerman, one of UCLA’s lawyers at the time, about the Rieber Hall rape case. “Our contention was that the security was adequate, that we did all we reasonably could without turning the place into an armed camp.”

But the lawyer employed more than militaristic imagery to defend his client. Zuckerman also argued the university should not have been held responsible for the 1987 rape in the first place.

“When you’re dealing with someone who’s a rape victim, there’s naturally, and rightfully so, a lot of sympathy for her,” Zuckerman told the Daily Bruin at the time. “(But) it wasn’t the university’s fault, it was the fault of the people who did the rape.”

And that’s perhaps the most troubling part of this saga about access control. Sexual harassment and assault did not see much recognition until the end of the 20th century, and a prevailing attitude toward these issues in higher education was that the institution should not be held responsible for these kinds of acts being committed on campus.

But in light of repeated instances of sexual assault – and later sexual harassment – institutions such as UCLA were eventually obliged – and rightfully so – to ensure a safe living and working environment.

And things seem to have improved since then. Access control on the Hill runs throughout the night and the guest entrance process is no walk in the park.

Celebrations are, no doubt, far from appropriate at this point, with the University of California system having paid more than $3.4 million in sexual harassment buyouts in the 2016-2017 year, and UCLA’s Greek life scene had yet another sexual assault incident last quarter.

Security in dorms is much tighter than it was decades back, however. And while UCLA still has a lot of work to do to address its sexual assault and harassment culture, at least we can take some solace knowing the university doesn’t consider UCLA Housing to be a militarized compound anymore.