Law school will always be a foster home for humanities and political science students wondering, “What now?” as graduation approaches. In an economy hostile even to south campus students, the detour from the world beyond academia seems all the more tempting.

The LSAT has seen an approximately 20 percent increase in test takers over the past two years. The upsurge in budding lawyers is substantial given that, since 2003, the number of tests administered has ticked up around 2 percent per year or even decreased.

If the economy can be blamed at all, this means that around 30,000 students are choosing law school simply to hunker down in academia until their job prospects improve. Pre-law students have always had to accept the label “pre-law” without an inkling of experience in real law practice. UCLA offers undergraduate law courses that approximate what one would encounter in the first year of law school, but these are not required of any pre-law student, putting the onus entirely on the student to seek them out.

Law firm internships are available in Westwood, but the 10-20 hour workweek of a clerk is not training for the 100 or more hours associates must sometimes pour in to the blue-chip firms undergraduates picture when legal work comes up in conversation.

The university has a responsibility to demonstrate the realities of being a lawyer not only to political science students but to all students in majors traditionally considered pre-law. Pre-med students are funneled into research during their junior or senior year. They have ample opportunities to observe medical procedures and doctors at work.

Pre-law students should be urged toward these kinds of hands-on experiences as well. There is no reason one pre-graduate school group should be favored over the other.

Pre-med students also have the advantage in that their majors are clearly defined. A physiological science major equates to a career choice in a way that English and history cannot.

The legalistic manner in which students are instructed to write essays only hints at pre-law. To be more explicit, the department could open concentrations in these majors that might include undergraduate law courses.

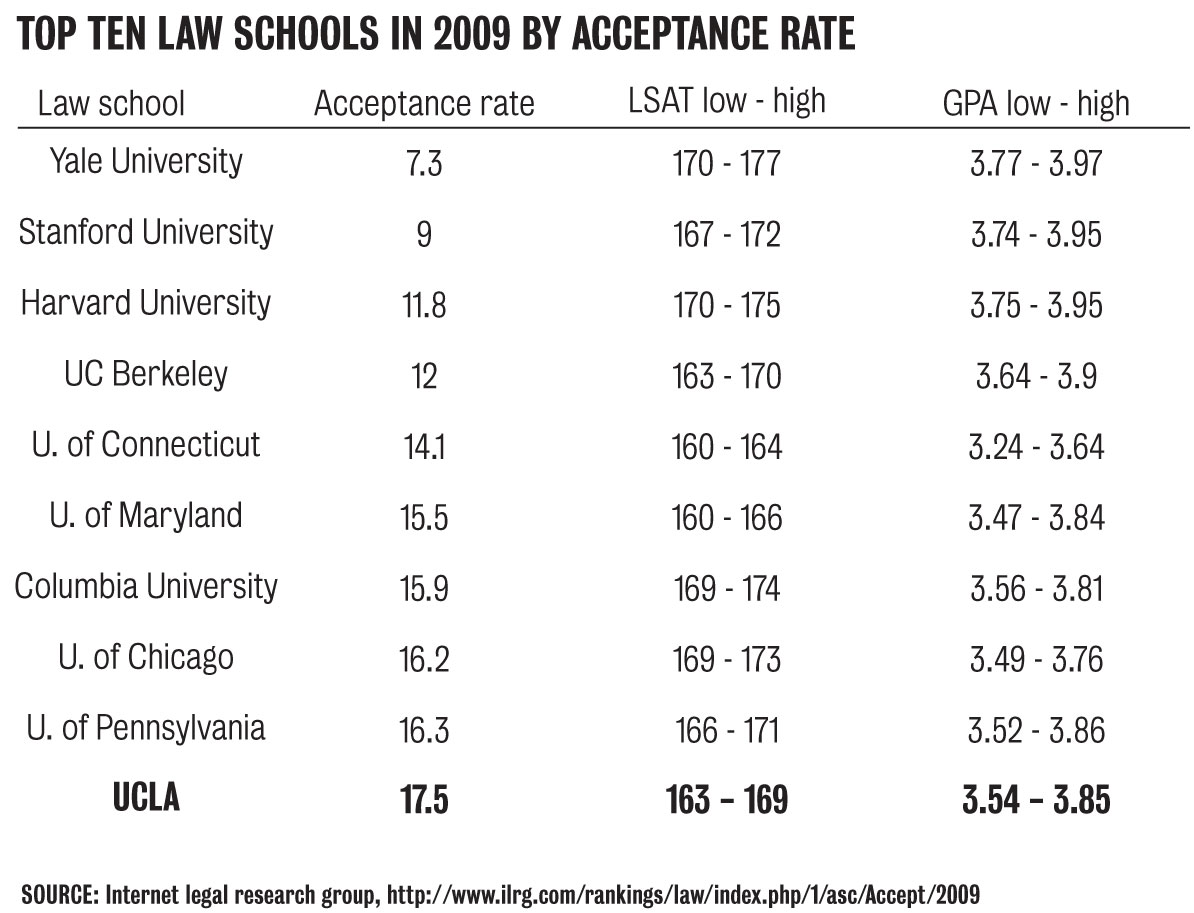

Any kind of new interaction between the law school and pre-law students would be welcome because the myth of the law student has been built up too much. Top law schools advertise irresistible graduate incomes of $150,000 and beyond, but they never mention that these employment statistics are self-reported and easily juked.

Hollywood’s representations of the lawyer as a Tom Cruise-looking, Jaguar-driving powerhouse aren’t helping either. And while most pre-law students can grok that Mr. Cruise’s fictional lawyer was probably more brilliant and conniving than they would ever want to be, his portrayal is just one of a myriad false representations of life after law school.

Students unconvinced of the improbability of driving the Jag should consider Northwestern University, which offers its unemployed graduates work at $10 per hour, or that many law firms don’t plan to reopen associate positions closed during the recession.

But more important than the possibility of top-tier and blue-chip is whether these are the only considerations pre-law students are making in their choice of career. They are not enough. Nor is it enough to panic at being undecided as graduation looms and fork over hundreds of thousands of dollars just to avoid being seen as undecided.

This is a situation the university could do better to help undergraduates avoid, but until it does, pre-law students need to find out what law means for themselves.