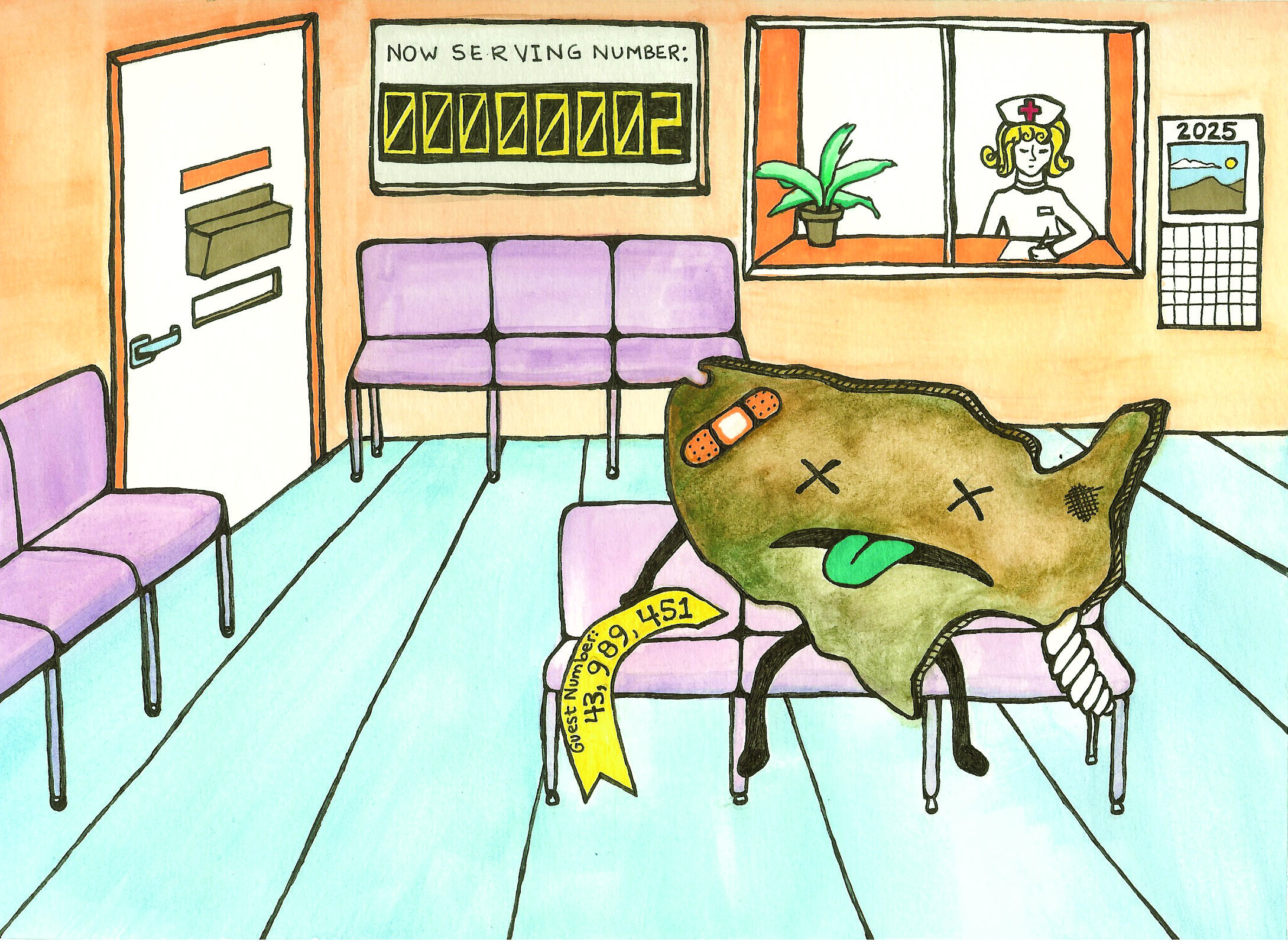

With the increasing strain on the nation’s health care system from aging baby boomers, greater longevity and the recent health care legislation, health agencies have predicted a deficit of up to 125,000 doctors by 2025.

In addition to the general shortage, reports have also warned of its effect on areas like primary care and pediatric subspecialties like child psychiatry, as these fields may attract fewer physicians.

The reasoning behind this is threefold, starting with the physician’s freedom to choose his or her field of medicine.

“As medicine gets more complicated, people tend to have smaller areas of expertise,” said Dr. Margaret Stuber, a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences in the David Geffen School of Medicine.

While specialization does result in better care, some students are motivated to practice smaller subsets of medicine based on the rate of pay, as specialists receive higher wages, Dr. Stuber said.

In addition, changing views about the expectations of doctors has resulted in more limited work hours for physicians, as medical schools now teach students to have balanced lives by taking care of themselves and raising a family, she said.

The disproportionate number of residency positions in hospitals for the many interested residents has also become an issue.

As medical schools have been asked by the Association of American Medical Colleges to increase enrollment by 30 percent, there are now higher numbers of students, but the same number of residency positions.

Since residents are paid through a provision of Medicare, hospitals cannot charge for services rendered by their students, Dr. Stuber said. Thus, it is difficult to expand the number of residency positions.

“Someone would need to find a way to pay for it,” she said.

There is also increased competition between the types of residency positions, as some areas, like dermatology and plastic surgery, are more popular than others, such as family medicine or psychiatry.

The bias against these fields is even prevalent in the Geffen School of Medicine, as there is a decreased interest in primary care, said Lawrence Doyle, executive director of the UCLA PRIME program, which studies health care disparities.

In response, new programs, like the UCLA PRIME program, have been created to encourage students to work in disadvantaged areas and thus develop the skills necessary for a primary care physician.

The five-year, UC-wide program combines basic medical education with a master’s degree in public health, public policy or business administration, and varies its focus at different campuses. For example, while UC Davis specializes in rural health, UCLA works to develop leaders for disadvantaged communities, with an emphasis on primary care.

Students work as part of a cohort of 18, and are selected from over 600 applicants, Dr. Doyle said.

The group trains and studies together, while also collaborating on a community project, such as washing feet at the Union Rescue Mission in Los Angeles. In this student-designed project, the group gave homeless people foot exams, since these people are on their feet for multiple hours a day. Along with podiatrists, the cohort shared health information with their patients.

Since the group learns together, Doyle said the experience helps students keep primary care and working with disadvantaged communities on their radar.

As a result, Doyle said he thinks students nationwide will increasingly go into primary care as medical schools like the Geffen School provide more options.

Like PRIME, programs geared towards inciting interest in child psychiatry are also a response to the expected shortage of physicians in the field.

For example, two summer fellowships for UCLA students, funded by the Rieger Foundation, immerse participants in child psychiatry, allowing the students to sample various aspects of the field, said Dr. Stuber, who is involved with the project. This one-month program is in its fourth year of existence and has been a success, as the first two Rieger Fellows are now involved in child psychiatry and pediatrics, she added.

Thus, with specially-geared programs designed to challenge students, doctors hope to encourage them to explore other fields of medicine.

“There are a lot of us around the country who want to reach out to med students early,” Dr. Stuber said.