The only thing that might seem more overwhelming than choosing which university you’re going to is choosing what you’re going to study. A major will determine what you study for four years, what philosophies you encounter, and what jobs will want your hard-earned skills and hard-learned knowledge. Your major will be one of the defining aspects of your college life.

A friend who has a passion for the English language, who is up to her ears in books and literature and who is probably the strongest writer I know, tells me that her mother has threatened not to pay tuition if she does not take on a scientific major. So she currently goes to college with an undeclared major and takes tentative bites out of scientific fields, unable to whole-heartedly pursue her passion without sacrificing tuition.

The fact behind her mother’s demands is that certain majors do yield better job prospects than others. For example, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the hiring rate in the computer science industry is expected to grow by 24 percent by 2018, while the Newspaper Association of America estimated that newspapers ““ a sector long fueled by journalism ““ dropped $10 billion in revenue from 2009 to 2010.

People will naturally gravitate toward majors that offer job security and a nice, fat paycheck. In this economy, a student of computer science may be set for life; a student studying English may have problems.

Sometimes, however, as illustrated by my friend’s dilemma, the choice of deciding a major is not left up to the student. Students often face a lot of pressure to choose a practical, “worthwhile” major that leads to jobs offering prestige, wealth, and life-long security. The people applying the pressure are almost always parents, but it can be self-inflicted as well. Students want to have successful, well-paying jobs, even at the risk of not enjoying their work.

There is a limit to how much practicality and future success should factor into one’s decision on a major. Websites with advice on picking majors frequently offer this question: What do you like to do? What interests you? But the real question should be: What makes you happy?

Life is too short to compromise between happiness and practicality. Majors are all too often stereotyped as being useful or useless: Chemical engineering is useful. Art history is useless. Political science is useful. English is useless.

But different people are talented at different things, and this is precisely the point. If we were all students studying “practical” majors, there would be vastly larger numbers of science and engineering students than there would be humanities and social studies students. But there would be vastly larger numbers of unhappy people, as well.

Some people are naturals par excellence at subjects like mathematics and computer science; they would be miserably unhappy if forced to take subjective, open-ended humanities classes. Some people are adept at understanding the cause-and-effect of history, the actions and reactions of people around the world and through time, but science is too cold and hard to be enjoyable for them.

There is another fallacy to the argument of major practicality: The knowledge one learns in a particular major is not always obvious or self-evident.

Philosophy, a major commonly derided as unusable in the real world, is rapidly becoming more popular on college campuses all around. In some universities, the number of philosophy students doubled over the course of a decade. Why philosophy? Because it strengthens students’ critical-thinking and analysis skills ““ useful talents in any career, especially in an extremely variable job market.

The hidden benefits of many seemingly impractical majors are the same: You learn not concrete knowledge, but more sophisticated and analytical ways of thinking.

If parents push you toward a certain field because it is stable or prestigious, undergoing four years of it will make them happy. But will it make you happy? The life of a student studying neuroscience and the life of a student studying philosophy are virtually different worlds.

Being forced into neuroscience will undoubtedly make a person whose true passion is philosophy unhappy.

So my advice is this: Find a major that you truly love. Find something that you just can’t wait to sink your fingers into, grapple with all its many facets and philosophies, and don’t compromise.

It might take a while to find something that claims all your devotion and attention. Studies say that nationwide, 70 percent of undergraduate students change their major at least once during their undergraduate years, and some studies suggest that students change majors up to three times on average. But too often we are told to follow our dreams, and too often they are somebody else’s dreams for us.

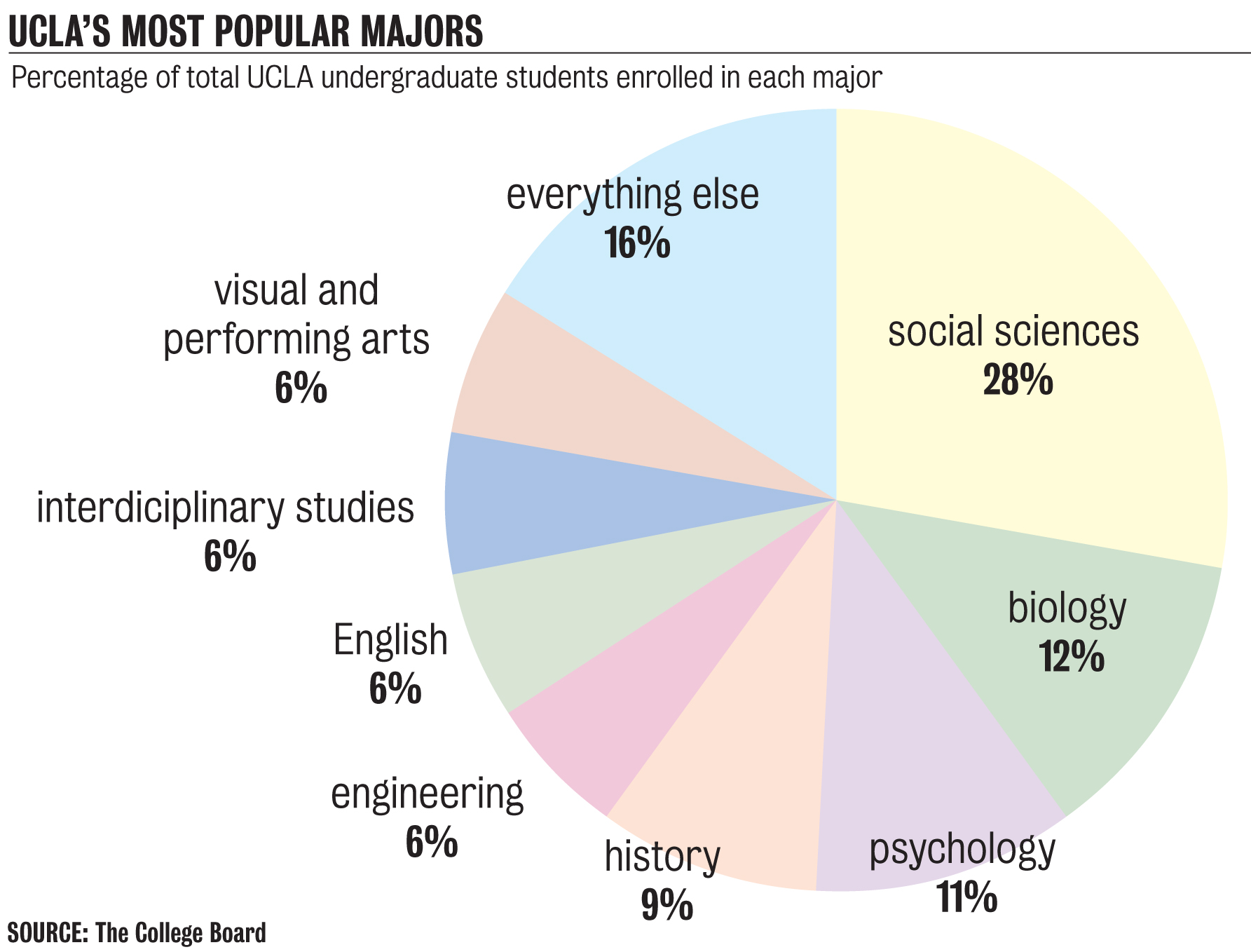

No matter what your dream is ““ mechanical engineering or comparative literature ““ run with it. There are 127 majors at UCLA (and endless combinations therein). If you really want it, it’s yours.