Graduate students at UCLA might have to pay taxes on money they don’t make.

The United States House of Representatives passed a tax bill Nov. 16 aimed at reforming the tax code system. Among the bill’s changes is the repeal of Section 117(d)(5), a provision that allows graduate students to not pay taxes on their tuition waivers. The U.S. Senate passed a procedural vote Wednesday on its version of the tax bill. The section repeal isn’t in the Senate’s current version of the bill but might be added when the two legislative chambers reconcile their bills.

Repealing the graduate tuition waiver exemption will have drastic effects on graduate students who receive tuition waivers in exchange for the work they do as researchers or teaching assistants. Under the current tax plan, UCLA graduate students only pay taxes on stipends they receive for fellowships or salaries they receive from the university for teaching or research. But with the new policy, graduate students would be responsible for paying taxes on their stipends, salaries and tuition, which could strain them financially.

Concern over the tax bill has not been lost on the University of California’s administration, though. UC President Janet Napolitano sent a letter to Congress in mid-November stating 23,000 graduate students in the UC system depend on $250 million in tuition benefits, which would become a tax liability to students if the bill passes. She added in a statement Monday that the tax plan would threaten the affordability and accessibility of higher education for many families.

Students have also been advocating against the bill. UCLA’s Graduate Students Association and Undergraduate Students Association Council’s External Vice President’s office organized events to protest the bill.

But UCLA needs to seriously evaluate how it will support its students if the bill is passed. To ensure that higher education opportunities remain accessible and affordable, UCLA needs to increase graduate student stipends and salaries. Otherwise, graduate schools will become more exclusive, and future generations of students will be financially discouraged from pursuing higher education.

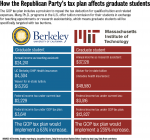

A financial analysis done by Vetri Velan, a UC Berkeley graduate student, calculated an estimate of how much taxes would increase for UC Berkeley students. An in-state graduate student earning an income of $24,000 a year would suddenly be responsible for paying taxes on $42,000 of income including their tuition waiver. They would have to pay $3,641 in taxes compared to $2,229. This 63 percent increase will affect students’ abilities to pay for housing, living and educational expenses without taking out loans.

A $1,412 tax increase doesn’t seem severe. But for a student living in university housing, such as a studio in Weyburn Terrace that costs $1,482 a month, the costs add up. After paying rent and taxes, a graduate student earning $24,000 a year would have less than $3,000 to pay for basic expenses, let alone educational costs.

Parshan Khosravi, vice president of external affairs for UCLA’s GSA, said the tax increases would exacerbate the students’ housing crisis, especially at campuses such as UC Berkeley and UCLA that are located in expensive housing markets.

“Students are not receiving a wage to be able to live in Westwood or other big city campuses,” Khosravi said. “The university needs to protect graduate students from this predatory attempt to strip students out of the little money they have.”

Additionally, the tax plan could prevent students from pursuing graduate education, especially those who come from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Todd Brown, a graduate student in psychology, said that unless the university offers financial support, the tax plan would discourage minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged students from studying fields, such as psychology, that have been trying to become more diverse over the last few years.

As such, UCLA needs to develop contingencies to financially support graduate students if the tax plan were to pass. One way to do this is to increase graduate students’ annual stipends by at least $1,000 to $2,000 to help offset the added cost of taxes. For the 13,000 graduate students enrolled at UCLA, this would cost the university an additional $12 million to $25 million a year, a maximum cost of less than 0.4 percent of UCLA’s current annual budget.

Although the stipend or salary bonuses would also be taxed, graduate students would still benefit. With a $2,000 increase in their income, graduate students will receive at least $1,700 to use to cover expenditures.

However, if the university did take the initiative to financially support graduate students, it might have to accept fewer graduate students to cover the larger expense. Accepting fewer graduate students would decrease higher education opportunities for prospective applicants and make it more difficult to offer enough discussion sections for undergraduate students on campus because of limited TAs.

But, as important as it is for UCLA to increase opportunities for graduate students and maintain undergraduate educational standards, the university must also ensure its current students are able to attend graduate school without sacrificing their quality of life or taking out thousands of dollars worth of loans to pay for their education.

A university isn’t a university without its students. And if graduate students are left to fend for themselves, UCLA may actually discourage its own students from pursuing higher education.

Only rich people should have their taxes raised. By “rich people” I mean people who make more money than I do.