In a 99-year life, there are a lot of paths not taken.

Years before any championship banners were hung ““ and even before he coached a single game at UCLA ““ John Wooden seriously considered the path leading out of Westwood.

As it stands today, the list of Wooden’s contributions to the UCLA community is astounding and his impact on the campus is still as visible as that of any other individual in the school’s history.

But without a couple twists of fate, that relationship could have been over before it started.

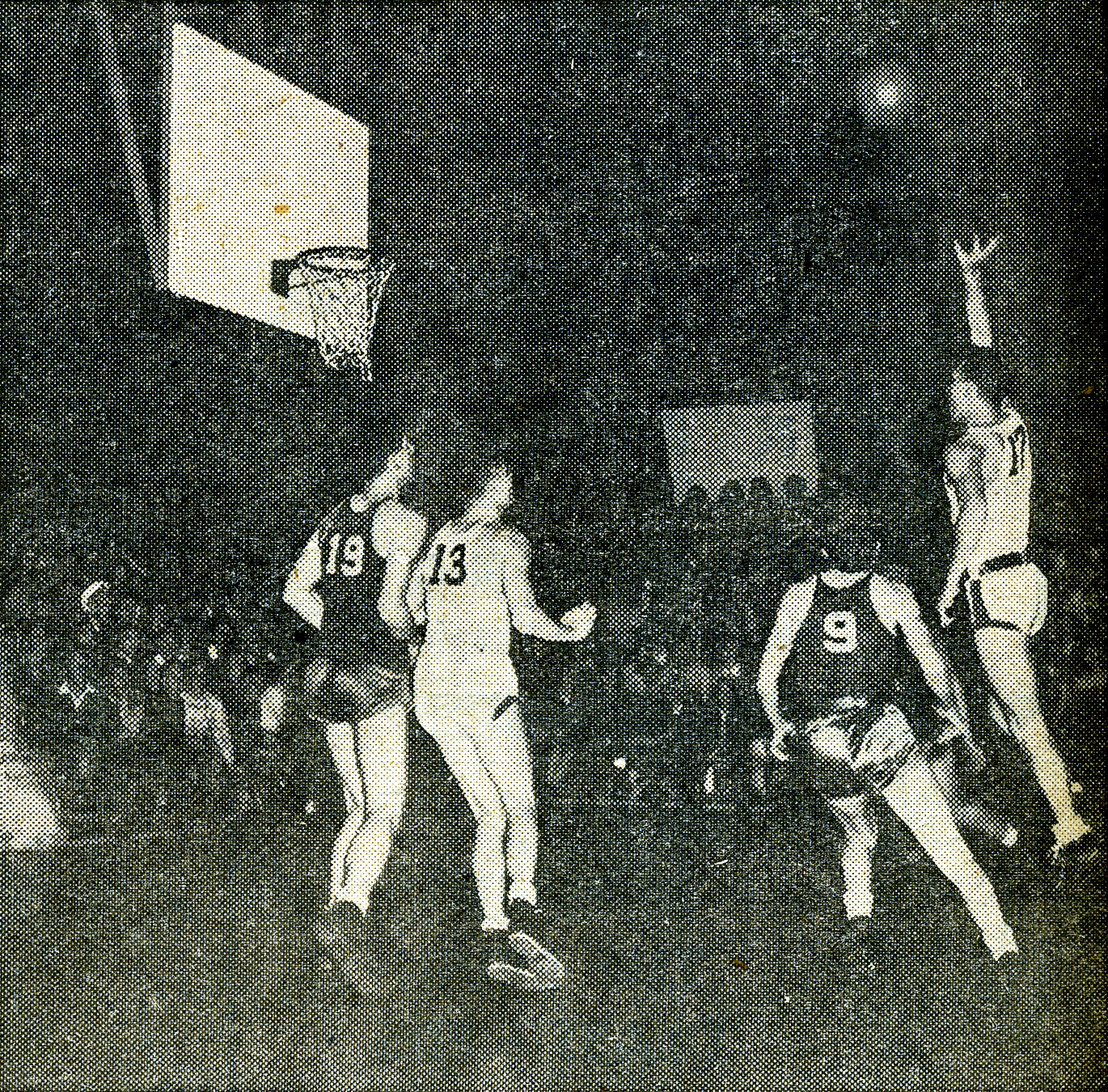

Hired by the school in the spring of 1948, Wooden arrived to find a ragtag group of current players, none of whom had been starters on the previous year’s team. In addition, the squad played its home games in a tiny, poorly ventilated gymnasium smaller than many of the high school gyms that Wooden had coached and played in back in Indiana.

“When I went up on the floor for the first time … and put them through that first practice, I was very disappointed,” Wooden wrote in his 2003 autobiography. “Had I known how to abort the agreement in an honorable manner, I would have done so.”

Like many stories about Wooden, however, this episode hinges on the man sticking to his principles and, luckily for the Bruins, it kept the coach out west for at least another season.

“That would be contrary to my creed,” Wooden wrote of the possibility of reneging on his commitment to UCLA. “I don’t believe in quitting, so I resolved to work hard, try to develop the talent on hand and recruit like mad for the next year.”

It was a significant challenge. Wooden had inherited a struggling program that, in 28 years, had amassed a record just three games above .500.

That first season, 62 young men arrived to try out for the new coach. Wooden whittled it down to around 20 who could survive his rigorous practices. Many of the players were forced to shed their occasional habits of drinking and smoking to keep up.

Eddie Sheldrake was a sophomore on the Bruins’ ’48-’49 team.

“Coach didn’t tell us not to go out at night,” Sheldrake said in Steve Bisheff’s 2004 Wooden biography. “He just ran our tails off.”

A poll of media members pegged UCLA to finish last in the Pacific Coast Conference that first season. Instead, they shocked powerhouse San Francisco on the road during a strong non-conference season and then ran through the Pacific Coast Conference’s Southern Division.

The Bruins lost in the PCC championship series, but in his first year, Wooden had led a mediocre team to its most wins in program history.

“We won many of our games that year, and in ensuing years, more on condition than we did on ability,” Wooden wrote.

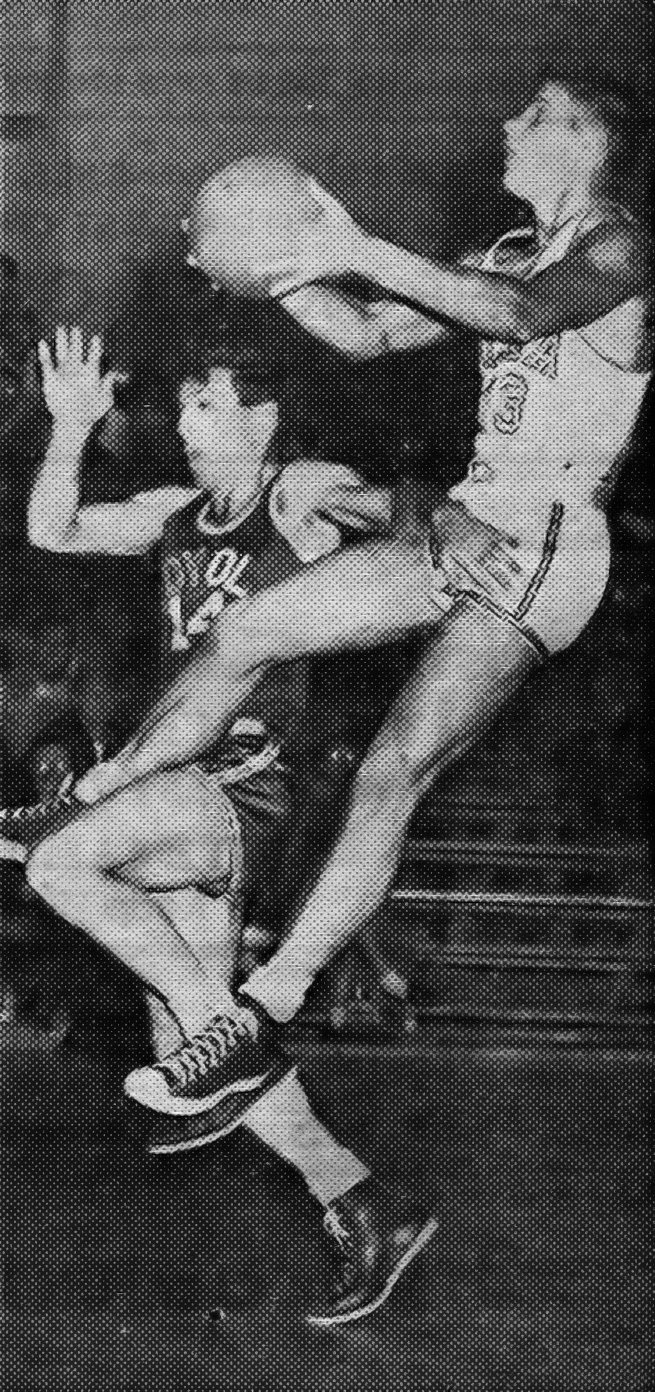

The next season, Wooden’s basketball philosophy was starting to become even more visible. UCLA ran a fast-paced style on both ends of the floor that demanded good conditioning from its players. The Bruins would again garner a marquee upset win, this time over future NIT and NCAA champion City College of New York in a game played at famed Madison Square Garden.

UCLA won 14 of 15 games to end its second season and earn its first ever trip to the NCAA Tournament, then just an eight-team competition. In Kansas City, Mo., for the opening round, the Bruins blew a late lead and went home disappointed.

“We had Bradley beaten,” Wooden wrote. “I goofed and the team made some mistakes, for which I’m responsible, but we could have won it. We could have gone all the way.”

But back in Westwood, the school was thrilled with the team’s sudden success and it wasn’t hard to see who was at the center of it all.

The 1950 edition of “Southern Campus,” UCLA’s student yearbook, described the scene as such: “Judged from all aspects, the past season has been the most successful ever had at Bruinville. They say that lightning only strikes once, but with John Wooden it’s an habitual thing, only each time it brings a bigger shock.”

The exuberance was not exactly mutual. That offseason Wooden was debating whether to stay in Los Angeles.

After his second season at UCLA, Wooden’s alma mater, Purdue, had come calling with determination. The Boilermakers were offering him much more than the Bruins’ $6,000 salary and their lucrative five-year contract was renegotiable after each season.

That’s not to mention Wooden felt a strong connection to Purdue and to his home state.

“I felt I was more of a Midwesterner,” he said. “The values and all, they fit me better and I felt more comfortable there.”

The typical lifestyle of a coach in Los Angeles at the time certainly was not for John Wooden. There were booster fundraisers and banquets to attend where the main activities were alcohol and loud conversation. The shy Hoosier mostly stood off to the side.

“(He) didn’t fit into the usual coaching clique,” Sheldrake said. “He didn’t like going to parties. He was more of a loner.”

For Wooden to leave, he would have to get released a year early from his three-year contract with UCLA, but Athletic Director Wilbur Johns and Bill Ackerman, then head of the Associated Students UCLA, were determined to keep the coach. They maintained that it was Wooden who had initially insisted on a third year and that by taking the Purdue job, he would be going back on his word.

Of course, Wooden could not go through with the departure if it meant all of that. Though irritated by UCLA’s hardball play, Wooden decided to stick around for another season.

By then, though, the coach had begun to plant his roots more firmly in the fertile ground of Westwood. His two young children had fallen in love with California, and Wooden had to admit he enjoyed being able to play rounds of golf all year round.

And as he was becoming ever more involved in the Los Angeles basketball scene, Wooden could see the region was in the midst of a talent explosion too tempting to reject.

Thirteen years later, John Wooden won his first NCAA Championship for UCLA, and 11 years after that, he retired as the keystone of one of sports history’s most enviable dynasties. But the values and principles that Wooden chose to live by are as much a part of his legacy as the titles and statistics.

When he first came to UCLA, Wooden had few ties to the start-up program on the far side of the country, but on multiple occasions during those early years he chose to be faithful to his commitments to the school.

There’s a reason that at the very base of the Pyramid of Success, Wooden’s renowned philosophical tool, is the foundational block dedicated to loyalty.