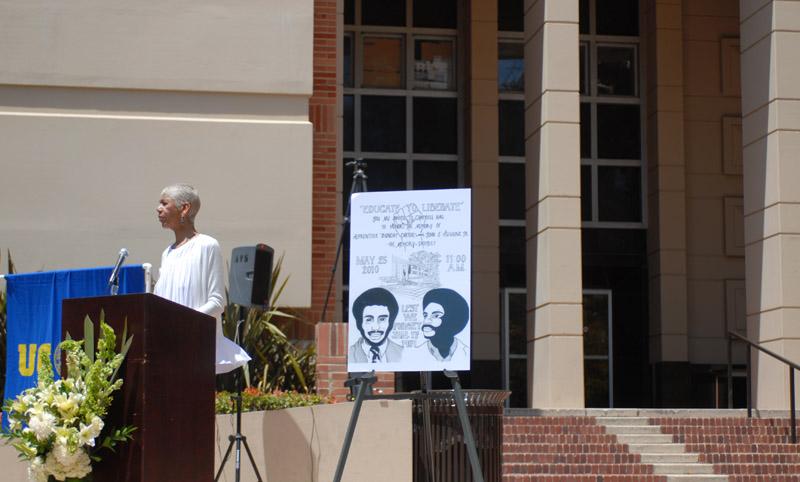

A crowd of about 80 people gathered by the steps of Campbell Hall on Tuesday to look back 41 years in history.

That was when Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter and John Jerome Huggins Jr., UCLA students and members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, were killed in room 1201 of Campbell.

At the ceremony, history lecturer Mary Corey, whose capstone seminar on 1960s activism is also known as the Memory Project, unveiled two plaques in remembrance of the Panthers, and their deaths on Jan. 17, 1969.

Elaine Brown, a former leader of the Panthers, stressed the importance of recognizing the bigger picture of the deaths.

“(The Panthers at UCLA) talked about bringing the skills of students back into the community, bringing the resources of the campus back into the community. We talked about uniting the community and the campus,” Brown said. “That was the message of John and Bunchy Carter.”

In 1968, Carter and Huggins were among the first group of students to be admitted to the university under the experimental High Potential Program.

This program was the stepping stone that preceded the Academic Advancement Program, Corey said. And during the jump from one to another, the shootings occurred, she added.

High Potential brought in 100 minority students who had been overlooked by the admissions office and who had demonstrated their capability for academic achievement, said Daniel Johnson, the program’s founder. At the time, Johnson was a 21-year-old political science student.

“The admissions office was largely white,” Johnson said. “So I created a program that outreached and found students who the university was not trying to attract unless they were athletes.”

Some of these students were leaders who were actively engaged in their communities, while others had academic accomplishments that were impressive in light of their setbacks.

“Can you imagine coming up with this idea, and presenting it to the school, and the school saying okay in 1968?” said Gregory Everett, who directed “41st & Central: The Untold Story of the L.A. Black Panthers,” a documentary about the Southern California Black Panthers.

In Los Angeles, it was a year characterized by frequent and violent conflicts between the police and the Black Panthers. The median age of the Black Panthers was around 19.

“It was a war zone here in Southern California,” said Bernie Morris, Carter’s older brother.

On the UCLA campus, Black Panther members attended class, but they also led protests and arranged for dining halls to donate leftover food to the party, which would then distribute the food in the community.

In the fall of 1968, UCLA students were discussing who should be director of the newly formed Afro-American Studies Center, Johnson said.

Ron Karenga, founder of black nationalist group US, lobbied Chancellor Charles E. Young to choose his preferred candidate without a student vote.

Simultaneously, the FBI created hostility between the Panthers and US to undermine the Panthers, 1975 Church Committee Hearings revealed.

The Black Student Union, now the Afrikan Student Union, asked the Panthers to help them maintain student control over the selection process. The Panthers agreed.

A series of meetings held in January 1969 to determine the director of the studies center were peaceful, Johnson said. But at the end of the meeting on Jan. 17, when most students had already left the room, Harold “Tuwala” Jones entered the room, Johnson said.

Huggins approached Jones, and the two entered into a verbal disagreement. Huggins took a swing at Jones, and Carter tried to stop him. As this was happening, Claude “Chuchessa” Hubert shot Huggins in the back, Johnson said.

When Carter tried to take cover behind a chair-desk, Hubert shot him, Johnson said.

“Bunchy was shot by what you call a dum-dum bullet ““ it expands when it hits the object. The bullet hit the wooden back of the chair, expanded, and entered Bunchy’s chest. It tore a gaping hole and the police said he was killed almost instantly,” Johnson said.

Huggins, who was also carrying a gun, reflexively emptied it as he was dying, Johnson said. At the time, he was 23 and Carter was 26.

After the shooting, Panther Elaine Brown, who was on the upper level of Campbell when the guns went off, returned to the house where she lived with other Panther members. “Within 20 minutes of our arrival, the police took us off to jail, charging the Black Panthers with preparing to retaliate against US,” Brown said.

Meanwhile, Johnson said he and other administrators of High Potential were placed under police preservation in the UCLA Guest House because it was unclear whether they were being targeted as well.

Later, L.A. police arrested three US members on suspicion of conspiracy and murder. Hubert and Jones escaped.

Huggins and Brown said they believe that the United States government played a part in orchestrating the shootings and in helping Hubert and Jones flee.

Johnson said he is still uncertain about what happened that day. He added that Hubert, who may still be alive, is probably the only person who could provide an answer.

Despite the shootings, Robert Singleton was chosen as the first director of what is now the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies in spring 1969.

In the months and years following the deaths, the Southern California Panthers continued their struggle against racism, but it was not the same, Morris said. “The energy in the chapter came from Bunchy, he was kind of the catalyst that made things go,” Morris said.

The university started to reevaluate the High Potential Program’s practice of admitting students, Johnson said. A study was published that showed High Potential students lagged behind their peers.

In 1971, High Potential was combined with the Educational Opportunity Program to create what is now the Academic Advancement Program. And now, Campbell Hall, which once housed the High Potential Program, is practically synonymous with the Academic Advancement Program.

But Carter and Huggins’ deaths go beyond Campbell, and even UCLA, Brown said.

“If this is (seen as) some little incident in some little hall, we’ll never understand the significance about their lives and deaths,” she said. “They wanted to unite blacks, browns, whites, Native Americans, gay (individuals), straight people, women. They wanted to humanize the country and effect progressive, radical change.”

Its a pleasure to see these men honored for their significant contributions to their community and beliefs.

Black Panthers did not fight against racism, they were racist, violent, Maoist bunch of thugs.

They also sometimes tortured and killed their own. Take Alex Rackley. Erica Huggins, John Huggins’ widow, participated in his torture and murder not long after the events in LA.

And what is with using outdated slang like ‘dum dum’ bullets? They were probably hollow-point bullets, a very common type of bullet.

Lastly, this shows why admissions should not be race based. UCLA foolishly admitted a bunch of thugs who engaged in a gunfight!