Why should the Mexicans be suffered to swarm into our settlements, and by herding together, establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours?

Eighteenth century diction notwithstanding, this idea perfectly articulates the phobia that fueled Senate Bill 1070 and holds back the DREAM Act. A similar quote was penned by none other than Benjamin Franklin. History buffs will be quick to point out that Mexican immigration was not an issue the Founding Fathers faced; of course, the original Franklin quote reads “Palatine Boors,” not “Mexicans.”

A Ben Franklin reborn in our time would find that the Boors did not tear the Anglo-Saxon fabric of his nation. They assimilated seamlessly and went on to brew Coors and author “The Grapes of Wrath.”

As an ethnic group, the Boors are considered one of America’s most successful. You might not have heard of them, though, because they’re called German Americans now. Or, more commonly, white people.

The American public might have taken Franklin’s paranoid delusions as a lesson and more readily welcomed the “new Germans” ““ the Irish ““ into the melting pot, but at the nation’s doorstep, these foreigners were bestowed with the title “scum unloaded on American wharfs.” The first generations of Irish Americans drove spikes into the nation’s emerging rail system. Their Italian successors worked sweatshops, and the Chinese after them panned gold from the rivers of California. All began at the bottom.

The unskilled immigrant laborers of the past differ from today’s undocumented workers in no fundamental way but legal status. Fans of Gov. Jan Brewer would argue that legality is the paramount issue of the immigration debate, and that illegal Mexicans cannot be the “new Irish” because the Irish broke into America legally.

Immigrants of the past, though, were not subject to the same kind of border patrol that blocks would-be Mexican immigrants. Ellis Island, the singular gateway to which over one-third of Americans (including, presumably, a few SB 1070 supporters) trace their ancestry, didn’t even require passports until 1918.

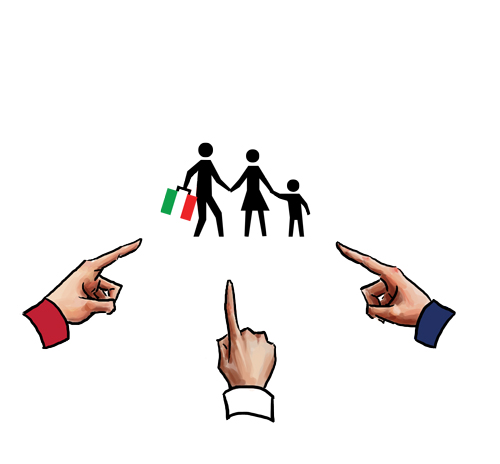

If the Mexican and Latin American immigrants branded illegal today had come this way, on a ship of whites who likewise hailed from society’s lowest rungs, they would have been processed and ushered into the melting pot the same way. Illegal immigration is a modern legal construct and little more than a means for nativists to substantiate the paranoia that earned Ben Franklin a scolding centuries ago.

As an aside, these references to Mexicans should be extended to illegal immigrants of all nationalities, but since Gov. Brewer’s SB 1070 ad mentions only Mexican gangs and runs footage of an “Adios, amigos” from President Obama, it’s clear that the legislation paints a specific target.

American nativism entered politics in the mid-19th century with the formation of various anti-immigrant coalitions, among them the American Republican Party. It was eventually absorbed by the GOP of its time, and like Gov. Brewer and her enforcement legislation copycats, it offered up immigrants as scapegoats in a time of economic instability and rising crime rate.

Anti-immigrant hysteria became the law of the land in 1882 when the wax of the presidential seal hardened on the Chinese Exclusion Act. Cheap Chinese laborers made their American competitors squeamish, so rather than give capitalism a pass, lawmakers succumbed to xenophobia and effectively banned Chinese immigration for over 50 years.

In retrospect, the act seems barbarous, and even those who hold illegal immigrants lopsidedly accountable for various societal ills would probably agree that exclusion was a step backward for a nation that has consistently prospered by accepting more immigrants than the rest of the world combined.

But in the sense that it could lead to the deportation of low-income laborers of a single ethnic group, even the current, unenforced federal legislation on which SB 1070 is based on might as well be called the Mexican Exclusion Act. The ideal America does not leap to exile millions of its residents at the first glint of an economic advantage for “natives.” Nor should all illegal aliens atone for the crimes of the gangsters among them.

History’s needless repetition appears even in the language of the Franklin quote above. What was called “herding together” in 1751 is now the common complaint that immigrant groups lock themselves away in “ghettos,” too holed up to be taken in by America. By now it should be clear that the diversity of an urban Los Angeles can only exist alongside nearly homogeneous ethnic communities like East Los Angeles and Koreatown, but the story of assimilation unfolds over generations, and all we see are the huddled masses of today.

Franklin’s fear of cultural poison ““ the “Language and Manners” that cross the border with immigrants ““ has also re-emerged, translated into another piece of Arizonan legislation. Worried about solidarity among minorities at the K-12 level, state lawmakers have sent Gov. Brewer a bill that would ban ethnic studies classes. She has until today to sign or veto the legislation.

Like the nativists of the past, the bill’s authors are crying foul at supposedly isolative practices that, in theory, do no more than instill confidence in minority students. If they’re not exposed to Cesar Chavez, young Mexican students only see their governor’s televised ads that associate them with gangsters, SB 1070 copycats in other states, and an entire block of society that looks at them with a paranoia that should have been extinguished hundreds of years ago.

E-mail Dosaj at tdosaj@media.ucla.edu.

Send general comments to viewpoint@media.ucla.edu.