Dan Guerrero’s executive responsibilities essentially mandate that he exude professionalism around the clock.

He’s gotten pretty good at it over his 23 years as a collegiate athletic director ““ the last eight of which he has spent as the head man at UCLA.

It’s hard to spot him without a shirt and tie. Even when sprawled out on the blue couch in his office, he’s wearing a sports jacket.

His office mirrors his attire. Four high-brow, important-looking certificates move horizontally across the wall behind his desk, perfectly and sharply aligned as if with a laser pointer.

When he speaks, he quotes Abe Lincoln, and he’s careful never to give too much of himself away. His diction is precise, his voice clear, his gaze fixed.

This is all very good, considering his professional responsibilities expand far past his day job in the J.D. Morgan Center.

Guerrero is one of a very small handful of Division I athletic directors of minority status, and he is the one and only Hispanic athletic director in the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision. He knows that many aspiring eyes are always fixed on him.

And now, after what he calls “the greatest professional experience of (his) career,” Guerrero finds himself just removed from being roasted in front of a national television audience as chair of the 2010 NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Selection Committee. Any eyes that were not already on him were on Sunday.

Professionalism, then, will serve Guerrero quite handily at this juncture in his life.

But what is all too easy to miss amid his eloquent, politically correct speech, his sharp attire and his striking office, is that Dan Guerrero is a native of the tough blue-collar town of Wilmington with patches all over his 3-year-old baseball jersey. He’s a dad that went to his fair share of music recitals and a man of faith who would pray anywhere, anytime, with any friend who needed guidance and spiritual support. He’s a guy that quit a lucrative job running a corporation for an unpaid job that promised only work experience.

And yes, his colleagues all seem to agree that he’s a natural-born leader.

Guerrero himself would never admit that, nor would he share thoughts about his personal life without prompting. Doing so would be unprofessional.

He does share stories about being an overwhelmed 19-year-old playing baseball in the World University Games against Cuba, listening to stands packed full of communist agitators with signs that read “Cuba si, Yankee no.”

He also tells stories about his time in Beta House, then a fraternity full of athletes. He admits that he, Bill Walton and several others would win intramurals every year.

But what might be most telling about a talk with Guerrero is the way his voice changes when he talks about his father. The carefully crafted articulation gets infused with passion, an almost gleeful tone, genuinely inspired.

Dan’s dear old dad is the man he most admires. The late Papa Guerrero would hit little Danny fly balls and grounders no matter how tired he was after a double shift at work. And he’d send a message to his son every evening when he tucked him in.

“When I went to bed every night my dad would come in and tell me I was the best,” Guerrero recalled wistfully. “I didn’t know what that meant, but I began to realize later that what he meant was that I could be the best at something. I didn’t have to be the best son or the best student or be the best whatever. But there was something out there that I could identify with, that I could have the opportunity to be best at.

“Really, a lot of who I am today is a direct result of his influence.”

Finding the “big time”

Guerrero’s father taught him as a kid the mantra, “big time is where you are” ““ a phrase that has stuck with Guerrero his entire life. Living by those words was important but difficult growing up in Wilmington.

It was important because Guerrero would have to do the best with what he had if he was going to succeed. It was difficult because he didn’t have much.

As a part of Wilmington’s American Legion baseball team, Guerrero would test if he really took his father’s saying seriously.

“We had about four or five bats for the entire team,” Guerrero said. “There were wooden bats in those days and God forbid anyone would break one because you’d be in trouble. It also just so happened that sometimes we had a coach and sometimes we didn’t.”

The poor financing would continue for Guerrero into high school at Banning, and he would get a tad jealous. Wilson High School, Millikan High School, and Lakewood High School all had rows of bats and a helmet for each player.

“I can remember one day after playing the team from Wilson, saying to my dad, “˜I wish I could play for a team like that.’ I got the best lesson I probably received in my life,” Guerrero said. “(My dad) said the only place you can impact, the only place where you can have the opportunity for someone else to see you, is where you are. And if you do well there, then people are going to recognize that.”

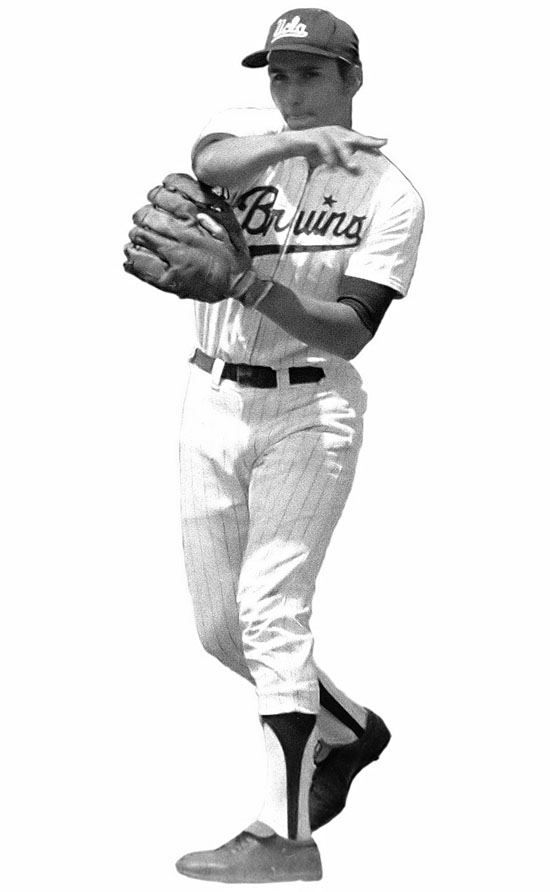

Perhaps with this in mind, Guerrero proceeded to try to become the best at something in baseball. He was a lousy hitter, but his father told him the hits would come. He excelled, however, as a defensive middle-infielder and people were taking notice.

One of those people was Andy Lopez, currently Arizona’s baseball coach. Lopez played against Guerrero at San Pedro, a rival high school and would quickly become a close friend.

“(Guerrero) preceded me to UCLA and I followed in his tracks,” Lopez said. “Little did he know he gave me a kind of hope: “˜Hey, that guy from Wilmington got in.’ He probably never knew that. He was inspirational for me.”

As Lopez alluded to, UCLA and other major baseball powerhouses took notice of Guerrero as well. But even then, the choice for Guerrero was easy.

“My dad always said UCLA was the university for the people. What he meant was that a person who looked like me would be welcome here.”

Lucky for Guerrero, he arrived in the middle of coach John Wooden’s 10 consecutive basketball national championships.

But a little known secret ““ Coach Wooden’s favorite sport is baseball, and Guerrero would be the direct beneficiary of that.

“He’d sit up in the stands, and we all knew he was there,” Guerrero recalled. “And it was funny that when he was in the stands, you’d play at a different tempo. You’re a little quicker, you’re a little sharper. You were more attuned and focused because you wanted to please him.”

Guerrero would not make it into the major leagues; a torn hamstring during his senior season would see to that.

But even coaches who had watched Guerrero as a college athlete at the University Games in Italy had taken notice of his considerable skill. Despite the fact he could not physically demonstrate and knew not a word of Italian, Guerrero would sign to play professionally in Italy and coach on the side.

He would return to the States at the age of 27, freshly retired, and having gotten a head start on a career path by working with the president of the Los Angeles City Council at home in the off-season. He nabbed a job running the Harbor Community Development Corporation of Wilmington. But after four years of that, he needed to move in a different direction.

“What was happening as a result of our success in the corporation was that people were looking at me as a possible candidate for office,” Guerrero said.

“And I knew I didn’t want to do that. Oddly enough, one of the reasons was I didn’t want a public life,” he added.

A humble beginning

It was then that he would embark on a career that would give him exactly that. Using his background running a corporation, Guerrero had also been teaching as an adjunct faculty member in the School of Management at Cal State Dominguez Hills, where Lopez was coaching baseball.

Lopez needed help raising funds for scholarships at the small Division II school. Guerrero’s experience in the public sector along with his grant-writing ability was a great help to Lopez, which naturally made then-Athletic Director Sue Carberry very interested in Guerrero’s services.

“I saw someone who had that gleam in his eye, who loved college athletics and wanted to see both boys and girls, men and women, move into the athletic world,” said Carberry, who at the time was one of the first female college athletic directors in any division. “It was his backyard that this was happening in. He saw an incredible future at CSU Dominguez Hills, who was very young at that point, who hadn’t really made their mark in athletics at all.”

Carberry would hire Guerrero as an Associate Athletic Director for no pay ““ an unheard of idea in the business today ““ and Guerrero, who had just become a father for the first time himself, took the job. The man who now sits in a vast third-floor office with a flat-screen TV, would sell concessions, chalk the baseball field and sell Goodyear Blimp rides to raise money for the athletic programs.

“Whenever I get off the phone with Danny. I say, “˜I love you, I miss you,'” Lopez said. “At Dominguez Hills it was a challenge, really a challenge. I mean we had no scoreboard. We had no irrigation system. I would literally go out and offer scholarships that I didn’t even have.”

Both men were stuck in an early and unsure time in their respective careers. Lopez was close to giving it all up, but Guerrero wouldn’t let him.

“(Guerrero) would come down (to the field) at a time when Andy Lopez was really questioning whether he should even be in this profession,” Lopez said. “Whatever was going on, he would be there and he would be an unbelievable source of strength. It was motivational. We would pray together in that dugout. We would ask for wisdom. He shared things with me, he would lift me up, he would really be a tremendous lifter of my spirits at the time.”

And as he was providing a source of strength for Lopez, Guerrero was simultaneously innovating by linking business to athletics ““ a new concept at the time. He created the Torero golf tournament and a summer sports camp for kids, from which all the revenue went back to the athletic department.

At the same time, he was developing his sense of how he might run an athletic department someday in the future.

“You could guarantee from then ’til ever that he was never going to bend or break to make something happen that he really wanted to make happen,” Carberry said.

It only made sense then that when Carberry retired and moved to Northern California, Guerrero took the reins and watched as Dominguez Hills won its first national championship on his watch.

Five years later, he moved up the ladder to UC Irvine where he would help raise several sports to national prominence and help generate $38 million in funding for athletic facilities.

One of the facilities was Anteater Ballpark, which opened in 2002 to welcome a baseball program back to UCI. This would prove to be Guerrero’s final year in Irvine, but he had worked throughout his tenure to get the sport he knew best back on campus.

Before he hired now-UCLA coach John Savage, he put in a call to Lopez who had three years left on his contract at Florida.

“Ironically, the things that (Guerrero) showed me at Dominguez Hills and had talked to me about earlier in my career at Florida is the reason I went back to Florida,” Lopez said.

“I felt that if I left Florida I was maybe running away, not really fulfilling my obligations. In my heart of hearts, I wanted to go work for Danny. I don’t know if I said that to him. I think the world of him but I really felt I had to go back (to Florida). Boy, I cried tears on that flight (home).”

Even without his old friend, Guerrero would establish a baseball program at Irvine that would eventually be ranked No. 1 and reach the school’s first College World Series in 2007, just five years after he left for UCLA.

Landing the dream job

All that success helped Guerrero land his dream job back at UCLA in 2002. And good work at his alma mater helped get him nominated by the Pac-10 to be part of the selection committee.

One of the members of the committee is Ohio State Athletic Director Gene Smith. Smith is the Vice Chair of this year’s committee and will fill Guerrero’s role next year after Guerrero’s five-year term expires.

Smith noted that the committee is going through a period of transition with three new members on the board out of 10.

Under such circumstances, he said the chair’s role as a leader becomes critically important.

At a mock selection exercise held a few weeks ago, Smith said Guerrero did something he had not yet seen in his three years on the committee.

“(Guerrero) would seamlessly identify moments where we had to pause and make sure the others were brought along,” Smith said. “At the end of the meetings when it was all set and done, he came to us just before the last piece and said to us veterans, “˜I’m going to point to each of you and ask each of you to share with the rookies something that you do as you’re tracking these teams.’ That’s leadership.”

A comfortable chair

It is clear then, that UCLA’s athletic director has an incredible amount of responsibility on his broad baseball shoulders.

Though Guerrero was thrust into the national spotlight on Sunday, Smith said that he and the eight other committee members felt at ease knowing that the chair would be more than comfortable representing the group.

Guerrero certainly looked the part, using his standard eloquent, politically correct speech and wearing, as always, sharp attire as he addressed a national audience.

In a word, he handled things “professionally.”

And, as he always has, Guerrero did his best to make his father’s words ring true.

Nowadays, “the big time” is where Dan Guerrero is, and he’s “the best” at a just about everything he touches.

If a lot of who Dan Guerrero is today is a direct result of his father’s influence, someone up there has a lot to be proud of.