UCLA offers hundreds of classes to its students. Tragically, however, no student will ever come close to taking full advantage of these wonderful educational opportunities.

Enter BruinCast.

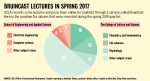

Every day, thousands of students use BruinCast, a UCLA service that provides video and audio recordings of lectures. Though most students use BruinCast to catch up on missed lectures or review material, BruinCast has potential as a valuable learning tool for both students and members of the public seeking to learn another subject in their free time.

At one point, about 25 percent of professors allowed their videos to be open to the public. Unfortunately, because BruinCast videos aren’t captioned, UCLA had to restrict access to BruinCast in 2015 to avoid violating the Americans with Disabilities Act, which mandates that video educational content must be closed-captioned.

Currently, BruinCast videos are not captioned and only accessible to individuals enrolled in the class. In order to promote a more open education, UCLA should reopen public access to BruinCast by providing closed captioning to recorded lectures for classes that are in high demand. This would enable students to access additional course materials, help transfer students adapt to UCLA and aid the university in its mission to serve the public.

Besides being a resource for students interested in exploring other fields, public access to BruinCast could really help a diverse range of students on campus. For example, BruinCast lectures from past years could help students succeed in their classes if they want to learn the material differently than how their professor teaches it. They could also help students decide which classes to enroll in beforehand.

Odel Zadeh, a first-year psychobiology student enrolled in Life Science 2: “Cells, Tissues and Organs,” said she would benefit from public access to BruinCast because she feels that adjunct professor Joseph Esdin’s, LS 2 lectures would match her learning style more than her current professor’s does.

Zadeh added public BruinCasts would have helped her decide whether to sign up for a chemistry lab class in the fall.

“I was interested in taking Chemistry 14BL in the fall,” Zadeh said. “It would have been nice to get a sense of the class beforehand.”

In addition, public access to BruinCast could also help transfer students better adjust to their classes at UCLA. Sheila Naby, a third-year psychobiology transfer student, said it would have been helpful to have public BruinCast access to see curriculum differences between UCLA classes and those at her community college. Naby said that having access to previous BruinCast lectures in the chemistry series would have helped strengthen her background in the subject when she took Chemistry 30B: “Organic Chemistry II: Reactivity, Synthesis and Spectroscopy.”

Public access would also help students explore studies outside their majors. A South campus student interested in learning more about history of witches in Western tradition might be interested in watching BruinCast videos on History 2C: “Mystics, Heretics and Witches in Western Tradition, 1000 to 1600” in their free time. Likewise, a North campus student interested in exploring organic chemistry could watch Professor Steven Hardinger’s Chemistry 14C: “Structure of Organic Molecules” lectures to expose themselves to the subject.

Clearly, public BruinCast access would help a variety of students. Unfortunately, legal and financial limitations have prevented UCLA from allowing professors to make lectures public.

Brian Haas, associate director of UCLA Media Relations, said access to BruinCast videos was restricted to ensure compliance with requirements for disabled students.

The cost of captioning BruinCast’s current lecture catalog would be expensive. Furthermore, captioning would be a lengthy process because transcripts would need to be at least 98 percent accurate to avoid legal issues, according to the ADA.

But UCLA isn’t the only institution to face this issue. Other high-caliber universities like Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology were sued by disabilities groups in 2015 for failing to provide closed captions for educational content they released online. Since then, these universities have reuploaded their videos with closed captioning. UCLA, on the other hand, chose to reverse its policy entirely.

Though the BruinCast office makes a valid argument about legal issues, public access to BruinCast would ultimately achieve the larger purpose of serving the public. College is supposed to be a place where doors to educational opportunities are opened, not closed. Limiting public access to BruinCast limits opportunities for all students.

Moreover, allowing the public to access BruinCast would better help UCLA fulfill its role as a public education institution. Education shouldn’t be limited to those who can afford to pay for it.

And in terms of funding, UCLA can raise money for BruinCast captioning with its Centennial Campaign and use platforms like YouTube and Echo 360 that already offer basic captioning services. UCLA could also save money by only captioning high-demand courses like lower division chemistry and math classes and popular philosophy classes. It could then expand those offerings as funds increase.

There are only so many classes UCLA students can take before they graduate – far too many to fit into the fast-paced quarter system. If students are to make the most of their education, public access to BruinCast is the way to go.

I like how the solution the author proposes is to “provide funding to caption videos” instead of to “protest the (supposed?) unintentional consequence of a law.” I am well aware that the ADA has good intentions and serves to help Americans with disabilities in other facets of society, but its ridiculous this inhibits what could be a greater benefit to society.

There exists a commodity with great value to society (uncaptioned lecture videos), but this commodity cannot be made available to society because it isn’t readily available to everyone in society (people who need captions that might have disabled hearing). Ridiculous.