Most people know who Charlie Chaplin is, but few college-aged students have actually seen his films screened properly with live accompanying music.

On Saturday, Dennis James is giving audiences a chance to experience in person what they only know by legend. He will perform alongside Chaplin’s “Easy Street” and “The Kid” on the 6,600 pipes of Royce Hall’s organ.

It may be difficult nowadays to experience a silent film the way it was meant to be, though audiences still are attracted to the aesthetic combination of movies on the big screen and live music. James said almost half his audience raises their hands when asked who has never seen a silent film with live music ““ and he says it is those people who keep coming back.

“It’s a wonderful thing that UCLA is doing this, and they couldn’t have picked a more spectacular venue than Royce Hall. It’s a great event for all ages that transports the audience back to the golden age of silent cinema,” said Phil Rosenthal, director of marketing for UCLA Live.

James’ father was an organ enthusiast and avid listener to “Inner Sanctum Mysteries,” a radio drama featuring organist Melody Mac. James became Mac’s pupil after a phone call and an audition, accepting the responsibility of keeping the music and tradition alive. He has since worked and toured with silent film stars Lillian Gish and Charles “Buddy” Rogers and has played all over the world.

“It’s beyond simply an influence. It’s more the passing of the responsibility of keeping alive the tradition that was extinct at the point that I was picking it up. I’ve given it an extra 40 to 50 years because of that,” James said.

His research and oral interviews with musicians, projectionists and theater managers of the silent film era have made James’ performances even truer to their original presentation.

A historical preservationist, James said he finds the music originally written for the film to play and has had people come up and tell him that he plays exactly the way it was back in the day.

From the early 1900s to the end of the silent era, the organ flourished as the primary medium for film accompaniment. It was more accommodating to film than a simple piano, yet it was not as complex as a full orchestra.

“The tonal versatility of a pipe organ much more suited the dramatic possibilities of music in conjunction with film,” James said. “The coupling of the organ with other media such as the silent film seems to give it a burst of new life, and it provides the vivacity that brings the spark of genuine, real experience to a reproductive medium.”

Both mediums add a new dimension to each another, and James helps facilitate this interaction.

“I’m carrying a dialogue on between the audience and the film. I’m kind of a mediator between the two,” James said. “They’re both temporal arts, they both take place in the passing of time. The passing of the visual image and the way the brain responds to it is nearly identical to the passing of time in the progression of music and how the ear and brain respond to it, so the wedding of the two is a natural, mutually supportive thing.”

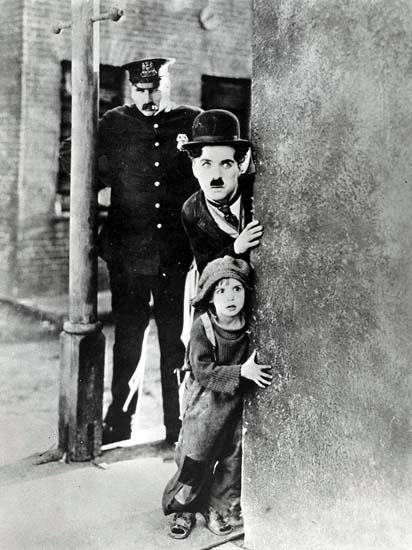

James’ film counterpart for his Royce Hall performance, Charlie Chaplin, is known for his physical dexterity that enabled him to perform spectacular comic sequences and a sense of humor that lampoons not just others but also himself.

“The Kid” was the longest original comedy focused on a comedian produced in American cinema at the time and still holds up today. Film and television visiting Associate Professor Jonathan Kuntz shows it almost every quarter in “Film 106A: History of American Motion Picture” and said it always gets a positive response from students.

“Chaplin was so popular because he was incredibly funny, and a lot of people could connect to his character, who was usually an underdog ““ a person on the bottom end of society who has to deal with the challenges of modern life,” Kuntz said. “A lot of people could relate to that struggle and were charmed and amused by the comedy he found in it.”

Kuntz said that those who saw motion pictures particularly in the silent era were part of the mass audience, comprised of the middle class, the poor, kids and immigrants. Few were part of the wealthy and elite class. Movies reached a wider range of people, as they do today.

“There’s this constant sense of re-discovery. The energy and emotional content that drives the art form as it was conceived still exists today. It has vitality; it’s something that still works to this day, 80 years later,” Kuntz said.