Imagine this: You have just decided to become sexually active. You are confronting fears about unwanted pregnancies, STIs and internalized stigmas about sex and your own body.

Now, you must navigate the process of getting contraception, which involves approaching a doctor you probably don’t know in order to discuss an extremely personal decision.

For many people, seeking out a doctor for a contraceptive prescription adds an unnecessarily stressful dimension to the process. In fact, a 2006 study found that women would more actively pursue safe forms of contraception if they could access these forms of contraception without a prescription.

Women seeking contraceptives no longer have to endure this undue burden. California Senate Bill 493, which passed the state Legislature in 2013 and went into effect April 2016, allows for licensed California pharmacists to dispense self-administered contraceptives without a prescription.

The new protocol requires that the individual seeking birth control meet with a pharmacist to have their blood pressure taken, fill out a medical history self-evaluation and receive sexual health counseling before obtaining the self-administered contraception.

This really helps women: It expands access to contraception by eliminating the need for an inconvenient and uncomfortable doctor’s appointment with a more impersonal stop at a pharmacy. It also initiates widespread, positive change by empowering women to go about getting birth control on their own timeline.

That is, unless you go to UCLA.

SB 493 does not mandate the new pharmacist protocol, leaving the University of California Office of the President room to support but not require the new pharmacist protocol at UC schools.

Since the law went into effect, UC Irvine and UC Berkeley have implemented the new protocol. For the past year, however, UCLA health administrators have been perfectly comfortable ignoring this opportunity to improve the standard of care they offer students.

But birth control accessibility isn’t just limited because there is a distinct lack of initiative on the part of the UCLA administration to adopt the new pharmacist protocol. It’s also limited because students are woefully under-informed about how to acquire contraception under the current system.

Piloting pharmacist protocol

Health administrators at UCLA’s Arthur Ashe Student Health and Wellness Center, the school’s primary medical care center, can minimize these current barriers by doing away with the required doctor’s appointment and implementing a pilot program to test SB 493’s pharmacist protocol.

This pilot program is feasible and John Bollard, chief of operations at the Ashe Center, affirmed that UCLA is discussing the possibility of bringing SB 493 pharmacist protocol to campus. But Bollard’s approach is anything but bold.

“This is not something we could accommodate on a walk-in basis, given current staffing. If we increased the staffing to have a pharmacist available at any time, we would have to charge the student for that visit in order to pay for the pharmacist,” he said.

Hiring additional pharmacists is not the only option, however.

UC Irvine only has one pharmacist. But Christina Fingal, a doctor at UC Irvine’s student health center, designed a solution during her tenure as medical director of the center: Students can fill out an online self-evaluation, then meet with a nurse to receive sexual counseling and have their blood pressure taken, as per SB 493 policy.

By making the self-evaluations available online, Fingal minimized the time necessary for in-person appointments. Using a nurse to perform the blood pressure test and sexual health counseling further reduced the burden on the campus pharmacy. Since UC Irvine began offering this service, more than 400 students have accessed UC Irvine’s site to receive contraceptives.

Given the success UC Irvine has had with this program, it is baffling why UCLA has not adopted a similar approach.

What’s more, UCLA’s current system puts students at a disadvantage. It is not only inconvenient, and nearly impossible on some days, to find time to go through the process of getting contraception during the Ashe Center’s hours of operation, but the current approach seems to ignore the emotional barrier it places on students.

“Of the 10 UC campuses, only five have pharmacies. Of those that have pharmacies, everyone seems to be saying the same thing, which is that the pharmacy is on the first floor and the same-day visits are on the third floor, so there’s no difference in access,” Bollard said.

Accessibility to contraceptives is not defined simply by how far a student must travel to obtain them. There is a marked difference between arranging a doctor’s appointment and simply dropping by a pharmacy – and it is not a difference that can be quantified by the number of floors you travel on an elevator.

Pursuing contraceptives is not just a question of physical accessibility, as Bollard suggests, but also one of emotional accessibility due to the stigmas surrounding female sexuality.

The decision to get birth control is even more difficult for students who come from conservative communities. Giving students the option of a getting birth control in a less intimidating environment, like a pharmacy, would make them more comfortable, and thus more proactive in actively pursuing safe sexual health decisions.

Chloe Pan, former co-director of the Bruin Consent Coalition and third-year international development studies and Asian American studies student, agrees with that notion.

“For me, as a woman of color from an immigrant background, there are a lot of stigmas I have to navigate when accessing birth control. Being able to access contraceptives on my own terms, like at a pharmacy, removes a lot of (stigma),” Pan said.

Our health administrators seem to recognize this concern. Bollard said UCLA health administrators have been looking into SB 493 pharmacist protocol as a way to increase contraceptive accessibility to students since the fall.

For a school that sells itself as a center of innovation and a home for trailblazers and leaders, UCLA trails pitifully behind its sister campuses, and even the corporate sector, in contraceptive access.

When the Ashe Center administration finally decides to actively pursue pharmacist protocol, however, it will have access to a plethora of information not just from its pilot program, but also from other universities and countless corporations, about how best to optimize and organize its efforts to increase access to contraceptives given that such pharmacist protocol has been in place at UC Irvine, UC Berkeley and countless corporate pharmacies for almost a year.

Educating the educated

Expanding student access to contraception through pharmacist protocol alone does not solve the larger issue, however, that students are fundamentally uninformed about the entire process of obtaining birth control.

And this is too bad, because although the Ashe Center should be more proactive in pursuing pharmacist protocol, their current policies and programs already do an incredible job supporting student health.

The Ashe Center makes it possible, for example, for students to refill their birth control prescriptions online. Health administrators have also made serious strides in increasing student access to medical care, through the walk-in clinic and the comprehensive affordability of UC Student Health Insurance Plan.

“Having access to UC SHIP changed my relationship with contraception – it gave me a sense of agency. For the first time in my life, I was able to make decisions about what I wanted to do with my own body. I was able to take care of my body and not worry about the financial burden of doing so,” Pan said.

Unfortunately, a majority of students do not take advantage of our on-campus access to contraceptives. They simply don’t know such programs exist.

The Undergraduate Students Association Council’s Office of the External Vice President has a health department which recently completed a survey evaluating how much students know about access to contraceptives on campus and the new pharmacist protocol.

While this survey revealed a majority of students, whether they were on birth control or not, were interested in bringing SB 493 to UCLA, it also showed that 60 percent of students don’t understand how to currently obtain contraception at school.

“We shouldn’t live in a society where it’s unsurprising that women are uneducated about their reproductive rights, their birth control rights,” said Dani Lowder, a first-year political science student who ran the survey.

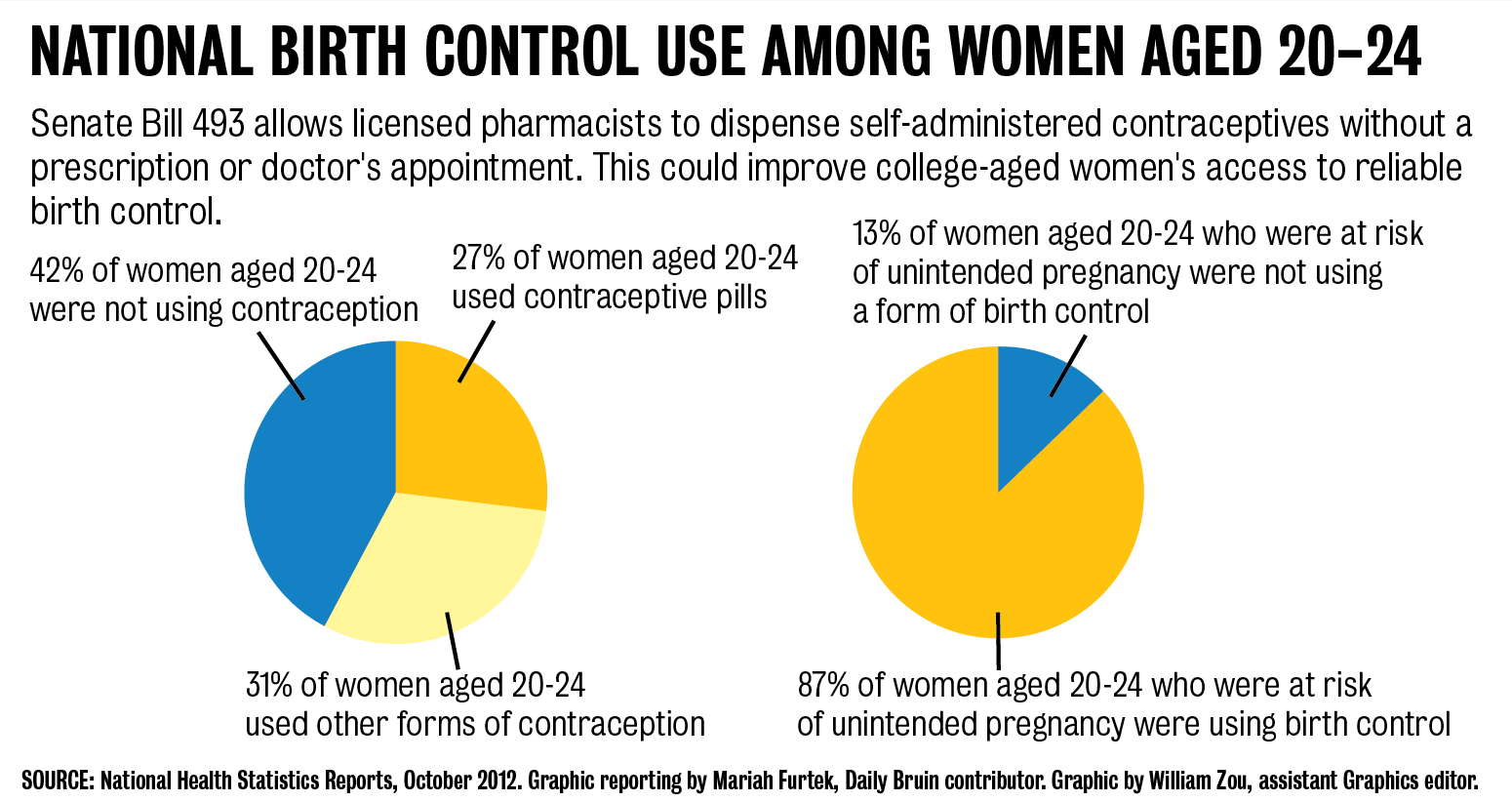

This echoes a real concern: Half of all pregnancies in California are unplanned. And these unintended pregnancies are most prevalent among college-aged individuals between 18 and 24 years old.

It’s necessary not only to just have access to contraceptives but also to have knowledge of how to take advantage of this accessibility. In addition to adopting the pharmacist protocol, the Ashe Center should educate students about their birth control options through a more relevant and far-reaching platform like a social media campaign.

“I definitely feel there is a need for further education about contraceptive access at Ashe,” said Christina Lee, a third-year psychobiology student and USAC Student Wellness commissioner.

This program could bring information about contraceptive accessibility directly to students via a series of seminars or an informational video posted on the Ashe Center’s website that explains the process.

Such educational programs would also normalize discussions of sex and contraception here on campus. This would teach students healthy methods of communicating about contraception, a skill paramount to ensuring that students engage in safe sexual activity throughout their lives.

This would be a stark change from current programs. As of now, student groups lead most efforts to educate their peers about access to contraception. For example, the UCLA Sexual Health Coalition runs an annual “Sex Week” presentation. While the Ashe Center participates in these events and tables for “Sex Week,” it doesn’t take much of an active role in leading these campaigns – something its revamped campaign should address.

Ultimately, the pilot program requires heightened educational outreach. By implementing both, UCLA can empower students to make healthy and safe decisions about sexual health. The educational programs will provide students the information and tools to have mature, well-informed conversations about sex while an embrace of pharmacist protocol will give them the agency to get birth control on their own terms.

UCLA promises to educate and empower its students. Our current approach to contraceptive access on campus, however, does neither.

This is not something health administrators can push off for another year. There is a very real cost to leaving students uneducated about their birth control options, to eschewing advances in accessibility of contraceptives.