The diagnosis of malaria may be possible with a simple stick of chewing gum.

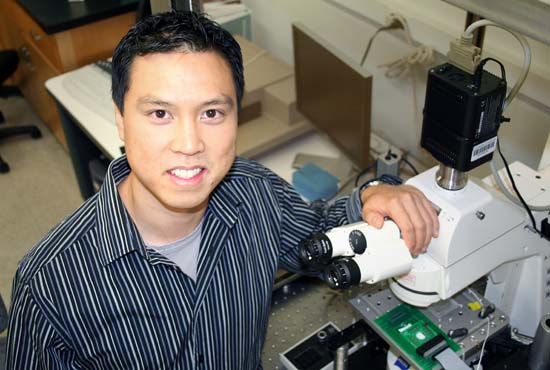

Andrew Fung, a UCLA graduate student, might be able to work around the fear of needles in malaria-infected patients in remote countries. He received a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation grant for $100,000 last month to research a method of diagnosing malaria with chewing gum.

A special kind of gum or candy would be the medium used to collect proteins in the saliva that are also found in blood cells. Ideally, a piece of gum would be given to the patient to absorb and collect the saliva.

The piece of gum would then be removed from the patient’s mouth. A magnet would collect the malaria proteins from the gum and form a specific line with a specific color that indicates not only whether the patient has malaria but also the specific strain of malaria that the patient has.

“There are many advantages to a saliva diagnostic,” said Fung, who will be using his grant to research the chewing gum diagnostic after he finishes his dissertation on microelectrodes for heart-muscle cells. His dissertation investigates the abnormal heart rhythm condition, arrhythmia. He is on schedule to graduate in June 2010.

“It’s easy to collect; I would just ask you to spit into a tube. It’s painless for you, and your nurse or doctor can get you to take it easily, and you could process an entire village this way,” Fung said.

This diagnostic would not only be accessible to more remote areas, but it would be very useful and easy when diagnosing children. However, the question that will be of central concern for Fung and his research team is if, in fact, the malaria cells that are in the red blood cells are also in saliva.

Professor Jack Judy serves as Fung’s adviser at UCLA and specializes in magnetic microtechnology. One of the major challenges that Judy foresees is “developing the right chemistry … (and) the packaging of that chemistry into a stick of gum.”

Malaria is a disease that infects the red blood cells and is prevalent in developing countries, especially in children under 5 years old. When the malaria parasite infects the body it takes residence in the red blood cells, multiplying there and secreting certain proteins, or biomarkers, into the bloodstream that are only characteristic of malaria, according to Fung.

“We want (a diagnostic) that’s noninvasive, meaning that it doesn’t require sticking a needle into anybody, and we want something that is accessible, meaning it’s low-cost enough and low-tech enough to send out to remote areas,” Fung said.

Researchers know that proteins can move from your bloodstream to your salivary glands, but in the process of doing so they become diluted so there are fewer of them. The diluted saliva makes detecting these malaria proteins more difficult, he said.

Fung, in his final year as a biomedical engineering graduate student, applied for the Gates Foundation grant last May. The proposal came about last year when he was trying to secure a professional research position for after graduation.

The Gates Foundation has given out the Grand Challenges Explorations grant only two other times in the past two years. The Grand Challenges Explorations grant is a smaller sum of funding given to explore the feasibility of a riskier idea. If the first stage of Fung’s research proves successful, he can reapply to the Gates Foundation for a second phase of funding, which offers $1 million for further research.

“I applied to this not expecting to get the grant really, but as a part of a preliminary job interview for the lab that I was interviewing for in Quebec,” Fung said.

The proposal was a way to show a creative but technical way of thinking necessary for a position in any professional scientific research group.

Also collaborating with Fung on this project is Dr. Theodore Moore, Director of the Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Program at UCLA, and Dr. Michel Bergeron, founder of the Infectious Diseases Research Centre at Laval University in Quebec.

The two most lethal strains of malaria are plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium vivax, which will be the primary strains that Fung and his team will be diagnosing for three weeks at a hospital in Palawan, Philippines, Fung said.

“That’s the hospital I’ve been going to since 1989, so I actually know the people very well and made all the arrangements for us to go out there,” said Dr. Moore, who has been thoroughly involved with the global health community, traveling most recently to Baghdad and Malawi, Africa. “The first shot in this is malaria, but we would like to get TB and HIV ““ really hit the big three and take care of all of them,” he said.

Concerning his general motivation to research this diagnostic, Fung said, “I think that in the end the purpose of engineering and science should all be to use these things that are built into the world and (to) use these things to benefit the world … I want to use engineering to make stuff like this that can hopefully help in an area of disease or help in some aspect of a quality of life of people somewhere.”