I cannot sew. I can’t cook either, and the few times I’ve attempted to make brownies from that Betty Crocker mix, I have somehow managed to screw up the entire concoction.

Unlike my mother and my grandmother, both born and raised in Iran, the role of these tasks in my life have been minimal. In a modern American context, these traditional tasks are often frowned upon, seen as outdated remnants of an earlier generation. For many immigrant families, though, great significance is placed on traditions such as cooking, with their generational repetition intricately tied to income, as well as cultural perpetuation in a foreign country.

I do not speak for all, or even most, American women, but as part of a younger generation that has seen domestic tasks wane in importance, it is easy to assume such undertakings by women have become somewhat archaic. The modern woman is focused not solely on creating a family as much as she is on furthering her education and career aspirations. Only the educated are truly liberated, and the limited opportunities for women my age mere decades ago make my own seemingly limitless choices as an American college student even more remarkable.

Looking at images of a 1950s June Cleaver, juxtaposed with the more modern Hillary Clinton, we can only marvel at the magnitude with which perceptions of women in the U.S. and their images in popular culture have evolved. Fueled by a surge in the female workforce during World War II, powerful images like Rosie the Riveter motivated women to do their part in the war effort. Feminist movements continued to change the role and image of American women. Baking and baby-rearing have given way to nondomestic occupations. Current estimates even predict that in this recession, there will be more women working than men.

Looking through such rose-colored lenses, we assume too easily that all American women, whether born here or halfway across the globe, should empower themselves through an abandonment of such domestically oriented roles. What many often fail to see, though, is how often these undertakings transcend the prevalent “housewife” characterizations in immigrant culture. What arises is a unique means of empowerment. These women not only preserve their cultures through these activities, but provide unique additions to the American story through their work. One example is the assimilation of traditional cuisines into American culture, as evidenced by the prevalence of everything from Chinese restaurants to kebab joints all across the country.

“When my grandma first immigrated (from Hong Kong), she was a seamstress, which was occupational and not so much domestic,” said Jessica Lim, a third-year international development studies student. “Cooking is used for family parties and certain traditions throughout the year. … For 80th and 100th birthday parties, the food is the same and symbolic. Noodles represent longevity and certain soups represent wealth.”

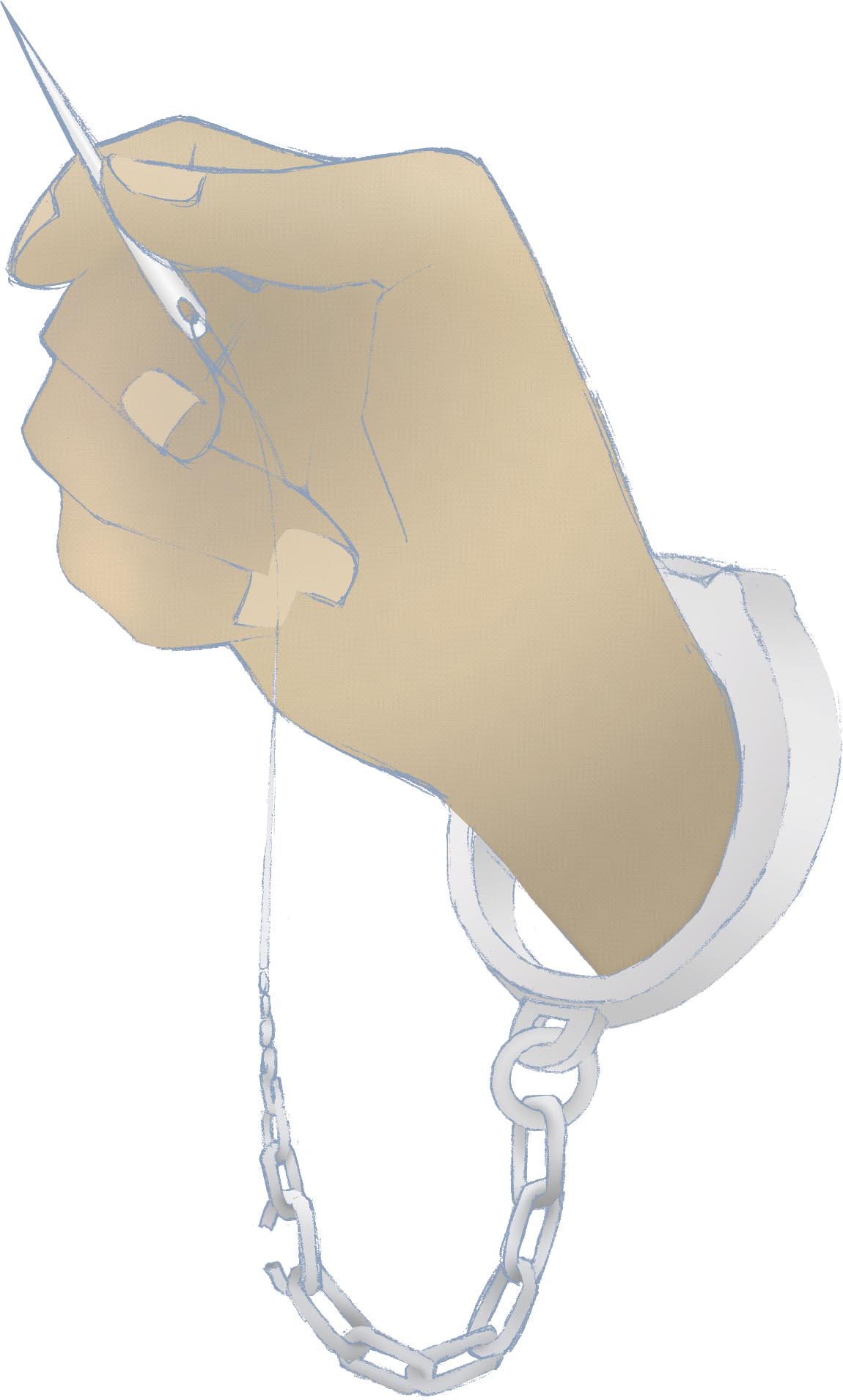

Cultural enrichment aside, many immigrant women made substantial monetary contributions to their families through these trades. My own grandmother used her sewing skills to help her husband provide for their family, using the trade primarily for income rather than for the household. Looking at concentrated immigrant communities, such as the city of Glendale, we find that these skills persist as a means of income, whether in restaurants or in tailor shops.

Despite lacking large-scale feminist movements like those seen in the U.S., countries from which many have immigrated saw the transformation of traditional “female” tasks as a means to support family. This gave many women significant roles as breadwinners in the family and as vital parts of their respective nations’ economies.

With language, religion and art considered among the most vital contributions of an ethnic identity, the importance of more domestically oriented tasks are often ignored. We cannot assume that the role of something like cooking or sewing in a foreign culture perfectly parallels our own American lifestyle and perspective. Dismissing these contributions to our own society would be a grave error, a denial of perhaps one of the most defining features of our nation.

E-mail Gharibian at cgharibian@media.ucla.edu. Send general comments to viewpoint@media.ucla.edu