Cameron Griffin wasn’t quite sure what to do.

The former linebacker had just bulldozed into the end zone for the first touchdown of his career against BYU – off a six-yard Josh Rosen pass – and all he wanted to do was tackle someone.

“I didn’t know what to do; I’d rather go hit somebody,” Griffin said. “That’s part of my world.”

But his world expands beyond the football field and out there, he does know what to do.

Rugby was his passport – his ticket out of the inner city.

Griffin, now standing at 6-foot-3, 240 pounds, was always the biggest one in his classes at View Park High School, but he wasn’t coordinated enough for mainstream American sports.

Basketball was out – he couldn’t dribble up and down the court. And swinging a baseball bat or a even a badminton racket with no hand-eye coordination was out of the question.

Then he found rugby.

It started as an easy-A middle school elective – playing a no-tackle, flag version in the school parking lot as a 13-year-old under Inner City Education Foundation teacher and coach Stuart Krohn.

But Griffin took naturally to it and try after try, rugby grew on him.

Griffin devoted each afternoon to practicing at a local park across from his house, running sprints to build his agility for sevens and bulking up for the challenge of full tackle rugby.

It paid off when coach Ken Henderson watched Griffin at a rugby game and urged him to try out for the View Park High School football team.

“He just said, ‘You’d be pretty good at football. Come give it a try,'” Griffin said.

The physicality of football and rugby came instinctively to the former three-star recruit who became the first person from his high school to earn a full athletic scholarship, but the leadership and maturity did not.

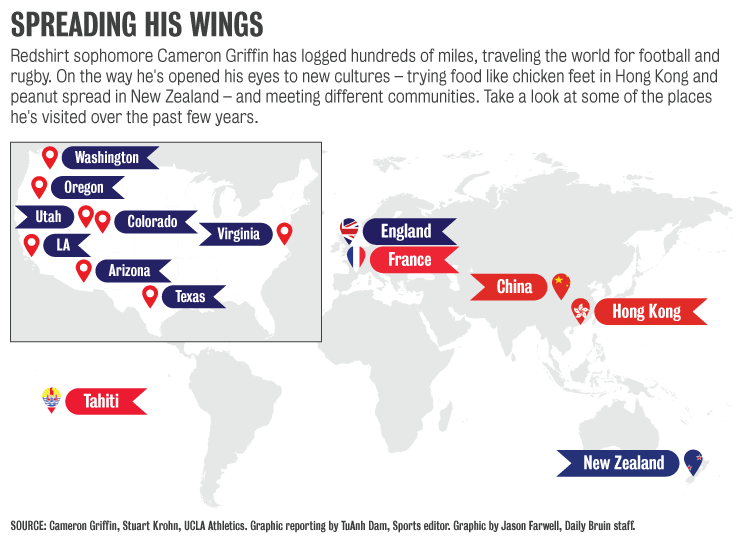

It took thousands of miles, four continents and a little bit of chicken feet to coax and nurture those qualities out of him.

At a crowded restaurant in China with Mandarin chatter surrounding them, the boys’ and girls’ ICEF rugby teams were attempting to immerse themselves in traditional cuisine.

A dish of steaming chicken feet sat next to a bowl of stewed chicken heads. The owner bustled out of the kitchen moments later carrying freshly cooked chicken tongues for the dozens of high school students.

Pushing away his trepidation, Griffin gripped his wooden chopsticks, shut his eyes and took a tiny bite.

It wasn’t so bad.

“I tell them to seize [the experience] with both hands. Eat the food. Try it. Taste it. It could be different,” Krohn said. “He was the most adventurous I would say, especially when it came to eating. He would try everything.”

Krohn, who traveled with the teams as the girls’ rugby coach and founded the ICEF rugby program, noted the growth in Griffin, whom he had known since middle school.

Their first trip took them to New Zealand, the birthplace of rugby.

Griffin hadn’t traveled outside the country before, but now he was flying 6000 miles halfway around the world.

The trip, from Auckland to Christchurch to Wellington, was about more than rugby.

On the pitch, they matched up to the high physicality of the locals, barely losing 27-25 after grabbing the half-time lead against one of the top college teams in the country.

But it was off the pitch, when the 38 athletes and coaches interacted with their host families or wandered the streets, that Griffin really got the feel of the country.

He tried learning the basics of the local language – laughing at simple mispronunciations – and went on scavenger hunts with his teammates throughout the city to learn the customs of the locals.

“It really molded me into the person I am today.” Griffin said “Coming to a school like UCLA, being surrounded by different ethnicities, being able to feel comfortable while being here and not being secluded to just my race. But being open to everybody.”

But Griffin and the other rugby players also acted as ambassadors for Los Angeles, dispelling black stereotypes and facilitating what Krohn described as “a true cultural exchange.”

They volunteered at local schools, taught kids the basics of rugby and shared stories of LA using any vehicle possible.

Rugby was one way he connected with the communities. Music was another.

Griffin was an avid guitar player, picking it up while visiting his grandparents in Mississippi.

On overseas trips, he would compose a song or melody with a teammate that they would share or perform for their hosts.

For the shy, reserved kid, it was a way to open up to people around him and connect with them.

Eventually he earned the chance to learn more about rugby and the country.

A New Zealand club offered him a scholarship to stay and train with them for three extra weeks after the tournament.

Although the opportunity was tempting, Griffin turned down the offer.

He had just begun breaking out, but he didn’t feel ready to completely leave his home and comfort zone.

And his mom wasn’t comfortable having him that far away from home either.

“I’m just a mama’s boy I guess,” Griffin said.

It wasn’t the right time to leave home, but trip by trip, Griffin knew how to push himself a little bit more.

Three years later, Griffin, bundled up with a UCLA beanie, signed a full-ride scholarship with the Bruins and was traveling through Europe with the ICEF team one last time.

The gaggle of laughing teenagers stopped to chat with a British man.

In the pouring rain, Griffin greeted the then-mayor of London Boris Johnson, now of Brexit fame, and shared with Johnson his previous travels before playing at Rosslyn Park.

Krohn was reluctant to have Griffin on the trip. The then-senior was nursing a shoulder injury, and Krohn did not want to jeopardize his football scholarship.

But UCLA coach Jim Mora personally called Krohn on behalf of Griffin and persuaded him to let the fullback go to Europe.

“He’s like, ‘I don’t want Cameron to miss out on this in high school. What’s the worst thing that could happen? He misses his freshman year,'” Krohn said. “He’s like ‘I want him to go on this trip. I want him to be a part of it. I care more about that. He’ll be a great player for us – his shoulder will get better and he’ll play for us. I really want him to go on this trip.”

Griffin, who had a passport full of stamps by then, was not the same kid who flew wide-eyed to New Zealand three years earlier.

Although he was still shy and quiet, he knew when to assert himself as a leader on the team, a person who, according to ICEF rugby coach Dave Hughes, “just gets it done” and was a role model to other players.

For Griffin, it wasn’t about always being adventurous with the food or speaking up all the time; it was knowing when to do so.

When the team struggled, dropping their first three games, Griffin and his best friend and team captain Leodes Van Buren Jr. rallied the team.

At a chapel in Devonshire, England, they helped pull the team together along with Hughes.

Griffin spoke up.

The emotional, personal stories about the struggles they faced growing up, from broken households to incarcerated parents to worries about paying for college, reinvigorated the team.

Even limited by a shoulder injury, Griffin wanted to turn around the momentum and team chemistry before they traveled to France.

He credits his rugby teammates with helping him stay focused on the future.

“We’re a special bunch, none of us are involved in gangs or drugs,” Griffin said. “If I even think about doing something wrong, they’ll steer me back into the right path.”

And that path took him around the world.