Video game companies and airline industries alike use virtual reality to explore alternate environments. Now, UCLA scientists are working to turn virtual reality into a tool that can help doctors better understand the human body.

Almost 1,500 patients have already received prostate cancer diagnoses using virtual reality technology, improving the diagnosis accuracy by more than 300 percent, said Erik Dutson, a surgeon at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.

Virtual reality can also provide an educational tool that shows medical students how to make accurate diagnoses and perform complex surgeries in a realistic environment, said Cheryl Hein, managing director for the Center for Advanced Surgical and Interventional Technology.

Peyman Benharash, a cardiothoracic surgeon at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, said virtual reality technology can be used to treat simple injuries as well as complex multi-organ damage during surgery.

“One of the things we have to do as surgeons is to see in three dimensions,” Benharash said.

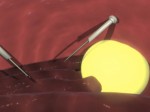

Using virtual reality technology, surgeons can build a three-dimensional model of the patient’s anatomy based on a patient’s CT scan. The model can then be used to identify the injury or area of concern. After the damage is localized, surgeons can rehearse the surgical steps required before the operation takes place, Benharash said.

He added virtual reality technology can also be used to improve teamwork by familiarizing a surgical team before the operation and minimizing both patient and surgeon anxiety.

Benharash is currently working on adapting virtual reality technology to injuries sustained on the battlefield.

“Virtual reality use in trauma is important in treating wartime injuries such as bullet wounds,” Benharash said.

Hein said surgeons can use virtual reality to overlay images of muscles, tissues and blood vessels on top of limbs to better visualize what they are operating on, but there are still challenges in implementing virtual reality technology in the operating room. For example, medical scans of an individual’s anatomy may be too complex to be converted into a virtual reality environment for use before surgery, she said.

“The human body is not made of rigid blocks of stuff – it’s soft and stretchy and not uniform,” Hein said. “We need to show how that material behaves in real life.”

Hein added it is also difficult to ensure that the virtual reality scenario reflects the entire body as a deeply interconnected network of cause and effect.

“(For example), bleeding in one place in the cardiovascular system can decrease blood pressure in another,” Hein said. “Virtual reality needs to be able to work in a full-body system.”

Dutson, who is using virtual reality technology to model penetrating injuries to the liver, said he thinks virtual reality will first be implemented in field clinics where doctors may not have the training to perform certain complex procedures.

“The technology is intended to train field medics,” Dutson said. “But as it gets more sophisticated, we can apply it to physicians.”

CASIT has also used virtual reality to improve prostate cancer diagnoses. Traditional methods of taking biopsies, such as inserting a needle, can be imprecise, Dutson said.

Ultrasounds, which are used to guide biopsies, are often not accurate enough to detect cancer, he added. Dutson said he thinks virtual reality technology is useful because it can depict injuries in real time and with greater accuracy.

“With virtual reality you can recreate injuries that are mathematically and physically accurate,” Dutson said. “Before (such models) were based on artistic renderings, but now we have the numbers. The potential benefits are almost infinite.”