The fourth post in a series on Westwood. This week: why – and how – the Westwood Village Specific Plan should be updated.

Imagine a Westwood Village with a lack of balance in its businesses: more than a dozen movie screens and 15 burger joints, but no grocery stores. On top of that, imagine having few pedestrian-oriented stores as well as noisy and congested streets.

Welcome to the 1980s.

After the Village had been the pinnacle of Los Angeles shopping and movie premieres for more than 40 years, it began to lose its charm. Westwood developers in the 1960s began to build movie theaters, replacing grocery stores and creating more fast food restaurants instead of sit-down restaurants. Westwood lost the balance of businesses that made it thrive.

Soon, there wasn’t a reason to go to Westwood Village. Consumers began opting for other shopping centers in the Westside, leaving many businesses to suffer. However, some residents and even the city did not want to give up on Westwood Village that easily.

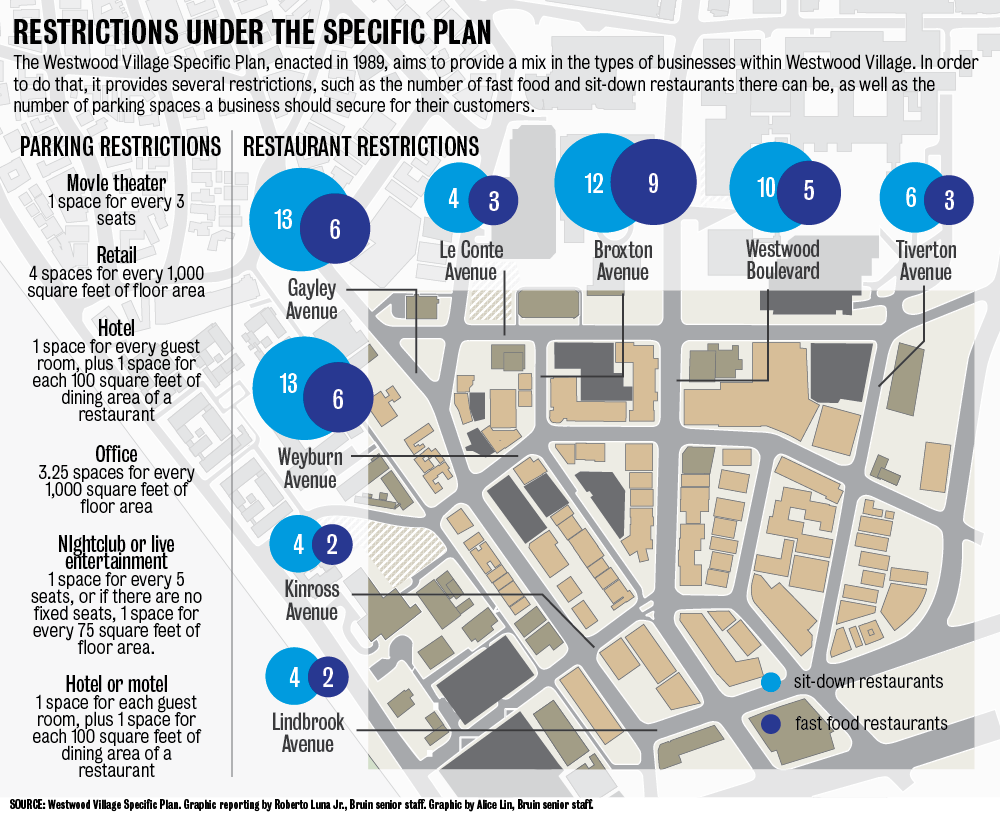

To alleviate mounting concerns, the city paid Gruen Associates, an urban-planning consulting firm, $350,000 to make the Westwood Village Specific Plan – a master-planning document aimed at maintaining the balance of businesses in the Village.

For the most part, it solved the problem it was trying to fix. It reduced redundant restaurants and called for more grocery stores. It also set a precedent to help maintain the Village’s historic Mediterranean-style architecture, which is distinct from the rest of the city.

However, the plan did not fix the entire problem. Between then and now, there have been numerous attempts at revitalization that failed. Even more so, there are about a dozen pizza places and many sandwich shops. There is a nail salon on nearly every block in the Village. The white and red lights on the trees of Westwood Boulevard seem to be the only source of vibrancy at night.

The problems intended to be fixed by the Specific Plan still exist today. But more importantly, it is an outdated plan and the 20-year-old document still dictates how the Village should be maintained.

It shouldn’t be dismantled completely, but rather updated, because it can continue to add a balance to businesses that appeal to both residents, students and the casual customers. Above all, it can help preserve the historical significance that can help it stand out from other shopping destinations.

Still, the plan in its current form unintentionally creates burdens on new potential owners, while ignoring the interests of some groups. Even the Westwood Village Improvement Association’s Robert York report concluded that the specific plan needs to be updated by 2020 because it outdated and often inconsistent with the current market and practices.

The plan creates a distinction between fast food restaurants and sit-down restaurants and limits how many there should be. However, there has been a rise in fast-casual restaurants recently that need to be taken into consideration that appeal to students. However, fast-casual restaurants are still considered fast food under the current plan and should therefore be updated.

Certain specific plan requirements also drive away potential business owners from the Village.

For example, the plan requires some business owners to have at least 4 spaces for each 1,000 square feet of floor space. The owners of Top Leaf, which opened in May, said they spent about five months trying to secure the mandated spaces. If new potential owners see it this as a hassle to move into Westwood, they might prefer to move into other places.

As difficult as having a specific plan sounds, a few other places around Los Angeles have similar documents.

The Pacific Palisades adopted their specific plan in 1985, aiming to to maintain the area’s character by putting restrictions on land use, building heights and parking while setting strict landscape and business sign standards.

Across the city, a portion of East Los Angeles adopted a specific plan in 2014 to revitalize the community around several Metro Gold Line stations.

Lastly, the financially successful Old Town business district in Pasadena has had a specific plan since 2004. Many have praised the district’s success over the past few years, mainly due to its parking meter revenue going towards financial improvements within the district. It began thriving even before its specific plan was made, and has continued to succeed since then.

Looking other specific plans may help, but one needs to look at what Westwood has right now and what it needs. And there is an option to do that.

Looking to fulfill the York Report’s recommendations, the Business Improvement District agreed in September to support a UCLA graduate urban planning class in evaluating the plan and offer recommendations. At that meeting, however, residents did not agree with the idea, and argued that the class was a waste of time and resources that would bring no results for the BID. The Pacific Palisades Community Council president at the meeting testified that the class, which had studied their specific plan, resulted in endless talks and no action.

This class, however, can be the answer for Westwood’s economic woes. Students are the ones that frequent the Village the most, but the class will not only hear from them. They will also solicit feedback from the community and could then develop concrete improvements. Updating the Specific Plan can’t be done by just one group.

It also means no one will ever have to spend $350,000 in the near future.

The Westwood Village Specific Plan can be a good thing. It has the capacity, with the proper involvement stakeholders, residents and students, to build an ideal Westwood that is vibrant and successful.