About five years ago, one of Mark Kaplan’s colleagues – a well-liked professor and scholar – committed suicide. Though Kaplan had been researching suicide for 17 years, his colleague’s death was the first time he was personally affected by the event.

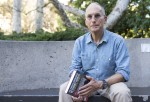

“It was an incident that was very touching to me,” said Kaplan, a professor of social welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. “I knew her, had conversations with her … As a colleague, upon hearing that she had taken her life, I thought this was one of those incidents that came very close (to me).”

At the time, the death changed how he and his peers interacted at work. It left a heaviness in the workplace – a sense of loss that lingered for months.

“Suicide does send ripples through the system, especially guilt among fellow employees,” Kaplan said. “(You think,) ‘What could I have done differently? Why didn’t I know?'”

Kaplan is one of a few hundred suicidologists in the United States.

His primary motivation for researching suicide is to make discoveries that could save lives. Kaplan said he thinks most people have been touched by suicide in some way, and many people in his field were survivors and knew someone who had died from suicide.

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S. About 40,000 suicides occur in the country every year, and for each death, it is estimated that there are 25 other people who attempt suicide, Kaplan said.

Though suicide is commonly studied in psychiatry and psychology, it’s rarely mentioned in terms of public health, Kaplan said.

In 1978, when he was a graduate student at UC Berkeley, Kaplan’s professor was studying suicides committed on the Golden Gate Bridge. He said this research opened his eyes to suicide as a public health issue.

“As a public health problem, I felt this was an issue that received very little attention,” Kaplan said. “As years went by, (the research) planted the seeds of interest in that topic.”

About 25 years ago, Kaplan started his career at the University of Illinois, working with a colleague to publish a series of studies on gun suicides among the elderly. Kaplan and his colleagues found that elderly men had the highest prevalence of gun-related suicides. They also found that the availability of guns has a direct correlation to the probability of gun-related suicide, and that restricting access to guns could potentially reduce suicide rates.

Since he started as a graduate student at Berkeley, Kaplan has authored about 90 papers, about half of which relate to suicide. In 2007, he published a paper on suicide risks among military veterans and was later invited to testify in front of Congress about the research.

Later, Kaplan and his colleagues studied the role of alcohol in suicide, finding that one-third of all people who committed suicide had consumed alcohol fewer than two hours beforehand.

Hearing stories from the families and friends of those who have committed suicide affects him personally sometimes, Kaplan said.

Because of this, he lives a balanced lifestyle to keep his mental and physical health up. He bikes six miles back and forth from work every day, eats a hearty breakfast and gets a solid eight hours of sleep every night.

Kaplan said his physical fitness helps him stay positive in the midst of his research as a suicidologist.

“I try to stay healthy because … suicide is a very depressing topic. There are many people who die by suicide who leave behind large families (and) that’s very troubling to me,” Kaplan said. “Suicide is (a field of research) where you have to take care of yourself.”

Because of the small number of suicidologists in the U.S., Kaplan said he wants to recruit new students in his field. He now serves as a faculty mentor for students who plan to study suicide at UCLA.

“He really pushes us to go above and beyond,” said Carol Leung, a doctoral student at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. “Sometimes it’s really tough. But in the end, when he sees us succeed or get a publication or award, you can just see his face light up.”

In his career, Kaplan has been able to coordinate an international research team with investigators from many different cities, said Bentson McFarland, professor of psychiatry, public health and preventive medicine at Oregon Health and Science University.

“Dr. Kaplan is cognizant of the important public health implications of the work,” McFarland said. “These studies are leading to policies that will reduce suicide.”

Although Kaplan has been a researcher for many years, he still gets excited about every new publication, Leung said.

“If anything, I think it’s more of his passion, his desire to really get this information out to the public,” Leung said. “I find that really admirable of him.”

Currently, Kaplan is working on two different studies: One that examines the effects of the economic recession on suicide rates in the U.S. and another on alcohol-related suicides.

“Knowing that perhaps this work might save lives – I can say that’s what keeps me going,” Kaplan said.