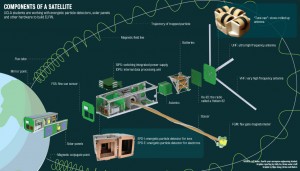

Ten subsystems, hundreds of design intricacies and thousands of hours of work by UCLA students will culminate in a satellite the size of a loaf of bread, which will be launched by NASA in 2016-2017.

The satellite – which will help scientists predict space weather – is the brainchild of Vassilis Angelopoulos, a professor of earth and space sciences and the principal investigator of the project, who brought both his past NASA project experiences and his drive for space projects to a team of students.

Four years after Angelopoulos first started recruiting students, the team has grown to around 50 undergraduate and graduate students with the same driven mindset.

Their space dream project – a small satellite known as the Electron Losses and Fields Investigation, or ELFIN – is finally ready to become a reality.

Angelopoulos said ELFIN’s two purposes are to study critical questions in space science and train students to work toward that objective on their own.

“At UCLA, we need students that can work with instruments and build entire missions to achieve their goals,” Angelopoulos said. “That’s why I have an interest in cultivating a new generation of engineers and scientists that can build such space experiments.”

After its projected launch in 2016-2017, ELFIN will analyze space storms by tracking the solar wind and radiation particles – electrons and ions – that enter Earth’s atmosphere. This radiation dominates around the equator but is defused by electromagnetic ion cyclotron waves, or EMIC waves. The waves scatter the radiation, causing the high-energy electrons to fall into Earth’s atmosphere, where they give up their energy through collisions, producing harmless auroras.

However, if the electrons stay in Earth’s atmosphere, they have the potential to disrupt space operations or even irreparably damage satellites and space infrastructure on which we depend for communications, navigation and weather monitoring. Magnetic storms can also affect electrical grids on Earth, causing blackouts.

“These issues are relevant and affect us now since we rely more on electricity than ever before,” said Jeff Asher, a fourth-year aerospace engineering student working as an overall systems engineer for the satellite. “Our goal is to advance the space weather model to predict magnetic storms and avoid damage. No one else has looked at where these electrons are falling out like ELFIN will.”

Angelopoulos said the knowledge from ELFIN will result in better radiation models that can predict the effects of these space storms and allow us to better protect hardware and humans in space.

Maxwell Chung, a graduate student in aerospace engineering, is working on the satellite’s payload, which tracks charged particles from the sun.

“My role is a bit different from the undergraduates’ because I play a mentoring role in electrical engineering,” Chung said. “For me, I got the chance to prove to myself that I knew it well enough to teach others.”

Chung said the payload includes two detectors – a magnetometer and a particle detector. As electrons and ions from the sun enter Earth’s magnetic orbit, the magnetometer will track electron movements along the equator while the particle detector will track ion movement.

The blueprints for the payload are known as PCBs, or printed circuit boards, which conduct signal connection, signal processing and power distribution.

“After working four to five months on the circuit board, it worked on the first try, and it was an amazing feeling,” Chung said. “It was the very first board that I worked on and it got me excited for the rest of the work ahead of us.”

Angelopoulos said the team specializes in a variety of disciplines, with more than half of the students studying mechanical and aerospace engineering and others studying the physical sciences, computer science and even the humanities.

For several years, the small team of undergraduate students worked with little internal funding and actively searched for outside sources to make the space dream a reality.

A breakthrough came in 2013 when the U.S. Air Force awarded the team a $110,000 grant to purchase materials and continue developing the satellite. In February, ELFIN was selected by the NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative. By working closely with NASA, ELFIN is now guaranteed a launch opportunity and will be given a ride on a NASA launch vehicle

“A great honor in itself,” Angelopoulos said about the ride with NASA. “Space is a tough business because it’s unforgiving. Once you go into space, you can’t fix it anymore. It has to work perfectly the very first time.”

On May 23, after one final push, the team was awarded $1.2 million jointly from NASA and the National Science Foundation. This was enough funding to ensure the complete manufacturing of the satellite hardware and operation of the satellite for six months from the UCLA Mission Operations Center, which will be located on campus.

Once the satellite is properly orbiting in space, UCLA undergraduate students will command the spacecraft, obtain data, and analyze and write papers on their findings.

Kyle Colton, a fourth-year applied mathematics student who works with ELFIN’s Communications and Earth Station, said ELFIN has partnered with W6YRA, UCLA’s amateur radio club, to build two stations at UCLA – one on top of Boelter Hall and the other on Knudsen Hall.

Colton added that ELFIN provided him the chance to build a high-altitude balloon payload and attend numerous conferences, including the Small Satellite Conference in Logan, Utah, where ELFIN was featured earlier this month.

“It’s a great way to establish contacts with people in the industry and start a relationship for future interview opportunities,” Colton said.

Along with job connections, ELFIN has provided students a learning process in a real-world setting.

“In an in-class project, there’s only one or two ways to do it, while satellite design is an iterative process where you design, evaluate, redesign, evaluate,” Asher said. “ELFIN is a living project – it’s always changing.”

ELFIN’s engineering model will be finished in the next year using funding from the U.S. Air Force, NASA and the National Science Foundation, with each subsystem going through multiple tests prior to final flight model development. Both the engineering and flight model will be tested using standard NASA practices, and the final model will be integrated into the rocket in fall 2016. The polar-orbiting satellite will collect data in the auroral zones and transmit them to the UCLA operations center, where students will be involved in operations and scientific analysis.

Angelopoulos said he would like similar experiences to continue with future undergraduate students. The plan is for another long-term, self-funded, continuous project to begin in two years so that the next generation of engineers passing through can be trained.

“Future ideas from this group of people in space science and engineering can become reality like ELFIN did,” Angelopoulos said. “This is just the beginning.”