A single row of handicap seats spans across the ground level of Drake Stadium. These seats tell the story of Milan Tiff, who brought them to life just over 40 years ago.

Tiff is not physically disabled himself, but he was. And he could be again.

After overcoming polio as a child, Tiff became a triple jumper at UCLA, where he won a national triple jump championship in 1973. But through all his championships and accomplishments, the polio never left him. To this day, he still has to fight against it, or else his lower body will become paralyzed again.

The Drake Stadium track is his medicine. At 67 years old, Tiff still trains there almost every morning to maintain his lower body strength and coordination.

“I have what they call post-polio syndrome, where your body never really rids itself of a disability, it (just) suppresses it. So unless you maintenance it, it can reappear,” he says.

“If I don’t (exercise), maybe a month, and I’m crippled again.”

The first step

For the first eight years of his life, Tiff couldn’t walk. He was born with polio, an infectious disease to the brain and spinal chord that causes paralysis.

Unable to attend public elementary school, Tiff enrolled in an art conservatory, where he developed a deeper understanding of his physical disabilities by drawing them out. He used illustrations to communicate his physical feelings with others.

“Whenever I was in pain, I could diagram it,” Tiff said. “When we would go to the doctor’s for treatment, they say, ‘Where were you hurting?’ And I would try to depict it in a drawing.”

At eight years old, Tiff began using his drawings as a tool to help himself walk. He traced the movements of animals in his backyard, and tried to repeat those same movements with his own body.

But for Tiff, moving his lower body was a process similar to someone trying to twitch an ear. It’s possible for an ear to move, but sending the mental signal to make it move is difficult.

“You have to sit there until you can get the signal to that fiber from your brain to make it function,” he said.

Tiff adapted his nerves to the point where he could crawl, but walking remained a struggle. His muscles were still very weak.

“My legs were so weak that they had to be put in braces,” Tiff said. “Walking was just too difficult.”

Yet, one day, a miracle occurred.

Tiff woke up, and he took a step.

Another step followed.

Suddenly, Tiff was walking for the first time.

To this day, he says he still doesn’t know how it happened.

“It’s unexplainable. You just wake up one day and there it is,” he said.

Bigger miracles were still to come.

From Step to Jump

During an eighth-grade physical education class, Tiff noticed a few of his peers competing in a long jump contest, and wanted to join in.

“I’m like, ‘You know what, I think I can do that,'” Tiff said. “I (asked) the coach for the … kids (without physical disabilities), ‘Can I try it?’ And everybody started laughing.“

What happened next could have hardly been predicted.

Tiff, who was still having some trouble walking at this point, strode down the runway. As he approached the foul line, he planted his foot and took off.

Tiff soared.

He remained suspended in the air longer than anyone else in his class. By the time he landed, his body lay outside of the sand pit – he had jumped over and beyond it.

“(I) don’t know what it was. It was some kind of strange coordination that I had developed from trying (to walk) in a crippled state,” Tiff said.

“That’s when I knew I had something else, something extra.”

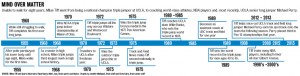

Tiff transitioned from the long jump to the triple jump in high school, where he continued his athletic evolution. He gained national recognition by having the third-longest high school triple jump and winning the NCAA indoor triple jump championship during his freshman year at Miami of Ohio.

Next thing he knew, a letter from UCLA lay in his mailbox.

Tiff accepted UCLA’s scholarship offer, and arrived in Westwood in fall 1970. With Tiff added to the squad, UCLA track and field won three consecutive national championships from 1971-1973.

But the trophies and individual accomplishments hardly encapsulate Tiff’s career as a Bruin.

While he triple jumped for UCLA, many physically disabled people came to Drake Stadium to watch him, inspired by his story. Tiff noticed that there were no seats designed to accommodate the physically disabled, and he did something about it.

“There was no access for (the physically disabled), so I had insisted that they put (chairs) in for the (physically disabled) people,” Tiff said.

Handicap chairs were added to the ground level of Drake Stadium shortly after that, and they remain there to this day.

So does Tiff.

Staying Strong

Tiff is at the UCLA track almost every morning. He’s been going there to work out nearly every day for the past 40 years.

“After he got out of college, he was always (at Drake Stadium) in the mornings,” said Jim Bush, the UCLA track and field coach from 1965-1984.

But all along, Bush didn’t know the entire reason why Tiff kept coming back. Tiff wasn’t merely training for pleasure or competition, he was training because he had to.

“I don’t exercise like the next guy would,” Tiff said. “He’s doing it based on something he’s read. I’m doing it as a result of (my condition).”

Nowadays, Tiff’s exercise regimen consists of about an hour of jogging, stretching and sometimes jumping. This formula helps him fend off paralysis and combat the physically debilitating effects of polio.

After his workout, he often enters a different realm.

The amicable Tiff begins sparking conversation with nearly anyone he encounters on the track, from the facilities managers to the UCLA track athletes and coaches.

When he sees people without physical disabilities trying to sit in the handicap chairs, he reminds them of their purpose.

“I tell all the kids that they were put in here for the disabled people; they were designed for that,” he says.

Tiff is not a coach on the UCLA track team, but it appears as if he is. His usual attire consists of a UCLA shirt and UCLA athletic shorts and running shoes, and there is almost always an athlete around him listening to his advice.

“He’s always helping some athlete,” Bush said.

In 2012, one of those athletes seeking Tiff’s advice was Michael Perry, a long jumper who had been cut from the UCLA track team after his sophomore year. Perry found Tiff on the track, where he was training to regain his spot on the team. The two quickly formed a bond.

“I looked at (Perry) and I said, ‘I don’t know why you’re not on the track team,'” Tiff said.

Tiff taught Perry some of the jumping techniques that worked for him in the past. Specifically, he changed Perry’s jumping style from the hang to the switch-kick method.

With Tiff’s guidance, Perry improved his long jump mark from being around 21’5″ to 23’8″ – a mark that earned him a spot on UCLA’s track roster in spring 2013. Now, as a senior, Perry is one of the top jumpers in the Pac-12.

“(Perry) would have never made it back without Milan’s help,” track and field director Mike Maynard said. “I mean he really did a great service to Mike Perry and really ultimately to us for his work.”

Perry was merely the latest athlete on a list of hundreds of athletes that have benefitted from Tiff’s coaching over the years. From Olympic track athletes to NBA All-Stars to non-athletes, Tiff has trained them all. Tiff’s success in coaching Perry proved that he is still as sharp as ever.

Another Day, Another Workout

Tiff sits down and stretches, extending his hand to his toes. His joints and muscles are as stiff as ever this morning.

“I still have pain to this day. Even when I (work out), it’s still painful,” he says.

But Tiff doesn’t show that he is in pain. He has adapted to the point that he enjoys it.

“It’s turned from what they call a pain to what they call a sensation,” Tiff says.

Tiff gets up, ignores his pains, and performs a few 100-meter dashes. Then, he returns to stretch out and loosen up his joints a little bit more.

Back and forth he goes, fighting against polio. He’s not going to stop anytime soon.

“This is gonna be my exercise all the way to the end,” Tiff says. “That’s why you see me here all the time, warming up and keeping it alive. It’s instinctive now.”

He sits down and stretches, with the handicap chairs that he insisted on building lying right there beside him. The chairs remind Tiff of where was, and where he could be.

But these also provide an everlasting reminder of Tiff’s legacy.

They remind him of the indelible marks that he has left on the UCLA track. They remind him of the physically disabled people who he inspired with his jumps.

They remind him of what his daily workouts have accomplished.

Milan helped me resume my basketball career after sitting out two years. Hurt my neck and thought I was done. Started working out with Milan as I had done earlier in my career. Got in such physical, mental, and spiritual condition I made it all the way back…

Just happened to find this article, and though I was a high school teammate of Milan’s (I was a sophomore when he was a senior and won The Golden West Invitational at 49’11”), I knew only that he “once” had polio. Never had a clue that it required such extreme, incremental “steps” to simply walk as a child (much less run or jump), and I would never have imagined that his ongoing fitness regimen was not just a matter of wanting to stay physically fit and active. Even more impressive to learn – these many years later – that he had overcome, and continues to surmount, such challenges in order to accomplish all that he has!

Note also, please, that Milan excelled in high school in several other events: LJ 23’4, HJ 6’5″ (straddle jumping) and ran a leg on our high school’s outstanding SHR team. Additionally, while he didn’t play basketball after high school, he was a phenomenal talent there, as well. His jump shot was nothing less than unblockable, even when he was guarded by athletes far taller than he.

One correction to this article, however: he is 65, not 67 years old…and looks far younger!