The multifaceted relationships between UCLA Health officials and the private donors funding their research have drawn scrutiny recently from experts and members of the university community worried about inherent or ostensible conflicts of interest.

At the forefront is billionaire couple Stewart and Lynda Resnick, two of the university’s most prominent donors and owners of pomegranate juice company Pom Wonderful.

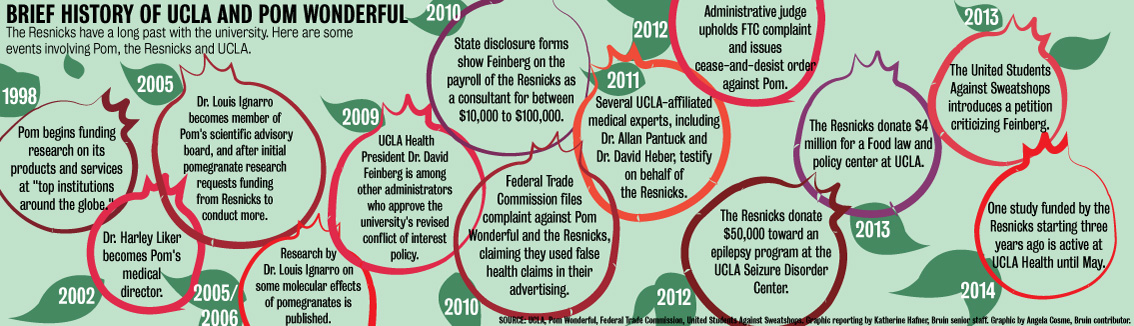

The couple funded a series of clinical studies over the past decade at UCLA to study their company’s products and services. The studies involved numerous departments within the UCLA Health System, from the Center for Human Nutrition to grants for doctors in pharmacology and psychiatry.

Their company, Pom Wonderful, sells pomegranate-based juices and pills marketed as a healthy choice.

One study on Pom’s products will remain active until May, according to UCLA Health.

A Federal Trade Commission complaint in 2010 found that Pom used false advertising to claim their pomegranate products had certain health benefits – calling into question UCLA’s role in any associated research used to buttress Pom’s ads.

Several UCLA-affiliated medical professionals have close ties to the Resnicks and provided expert testimony on Pom’s behalf in front of the FTC.

UCLA Health President David Feinberg was on the Resnicks’ payroll as a consultant during a period some funded research took place, earning more than $100,000, according to state disclosure forms.

UCLA maintains that it is dedicated to supporting the public trust.

But for some bioethics experts, such relationships raise issues beyond the blurred lines of industry-sponsored research.

UCLA’s connections with Pom Wonderful bring to the surface a deeper concern about the ties UCLA has with the Resnicks, a lenient conflict of interest policy within the university’s health system and a hesitance for the university to change course when faced with public criticism.

Research under fire

The Resnicks own a vast business empire that includes the holding company Roll Global, which oversees several companies, such as Pom Wonderful and Fiji Water. Stewart Resnick is a UCLA alumnus.

Forbes Magazine estimates the Resnicks’ net worth at $3.5 billion, ranking them among the wealthiest 152 billionaires in the U.S.

The couple has donated at least $16 million to the university since 2000, according to Milliondollarlist.org, which tracks publicly announced charitable gifts.

The couple is also the namesake of the Stewart and Lynda Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at UCLA.

Most recently, the Resnick Family Foundation donated $4 million to the UCLA School of Law for a new food law and policy program.

Before the Federal Trade Commission complaint in 2010, the company made health claims, including that “pomegranate juice is effective in combating free radicals that may cause a number of afflictions, including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, premature aging, Alzheimer’s disease … even cancer.”

In the FTC’s analyses of specific advertisements, several advertisements reference UCLA studies or comments from UCLA doctors in relation to “promising” results of research on pomegranates and prostate cancer. The FTC found more than 30 examples of misleading advertisements the company made regarding supposed benefits of its juices and pills.

The results were situated by the company as coming from the more than $35 million it spent “to support scientific research on Pom products at top institutions around the globe,” including UCLA, according to its website.

In May 2012, an administrative law judge upheld the Federal Trade Commission’s complaint and issued a cease-and-desist order against Pom, barring the company from making certain claims and stating there was “insufficient competent and reliable scientific evidence to support claims that Pom products treat, prevent, or reduce the risk of heart disease, prostate cancer, or erectile dysfunction, or are clinically proven to do so.”

Pom’s website now includes a disclaimer that its health-related statements “have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration” and its products are “not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” In 2011, before the ruling, the company did not use such a disclaimer.

The entire sequence of events between the FTC and Pom included a back-and-forth of accusations by the commission raising questions about scientific validity of certain studies, and responses by Pom that their advertising strategy is common and within its boundaries as a company.

Many UCLA doctors were caught up in the exchanges.

The FTC mentions several UCLA professors’ studies or comments in its evidence that Pom’s advertising was misleading, including a study released in 2006 conducted on pomegranates and prostate cancer by Dr. Allan Pantuck, the director of the Genitourinary Oncology Program Area at UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. The Resnicks financed Pantuck’s study for almost $480,000.

Pantuck is an associate professor of urology and has conducted several studies on the effects of pomegranate products.

According to the FTC, one peer who reviewed Pantuck’s study for consideration in a medical journal called the manuscript “excessively advocatory of pomegranate juice as a treatment for prostate cancer,” and rejected it.

The FTC also pointed out potential lapses in transparency on the part of the company and doctors, stating that a co-author on Pantuck’s study, UCLA internal medicine specialist Dr. Harley Liker, identified his affiliation with UCLA in the report but not his position as medical director for the Resnicks’ company.

Pom asserted that identifying solely academic affiliations is common practice, and also argued that the fact the study was published in the Clinical Cancer Research journal is “significant evidence that the research was scientifically valid.”

Liker has served as the Resnicks’ personal physician and became Pom’s medical director in 2002, according to FTC documents.

The FTC criticized the way Pantuck’s study was conducted, saying further research using better methods is necessary in order to validate various scientific conclusions.

The Pom-sponsored UCLA study conducted by Pantuck included 46 patients, all of whom had previously been diagnosed with and treated for prostate cancer. The study did not include a placebo group, which is a control group researchers often use, designed to give no treatment so their results can be weighed against the effects of the real treatment.

Pantuck and UCLA professor at the department of medicine Dr. David Heber, who both testified on Pom’s behalf, argued against the necessity of randomized controlled trials, stating that often the level of certainty necessary for a doctor before he or she recommends a treatment clinically does not always require randomized controlled trial-based results.

Heber testified that the trials, which can take decades and thousands of patients, are often “infeasible and too expensive to conduct.”

Close ties

Regardless of questions surrounding the validity of Pom’s scientific claims, some experts are wary of the level of contact maintained between the company and UCLA researchers throughout the time certain research was performed.

Eric Campbell, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who specializes in bioethics and medical conflicts of interest, said he would be very skeptical of any research coming out of UCLA related to a company like Pom that has such deep ties with the university.

“At some point, the relationship becomes so pervasive that you have to be skeptical about anyone weighing in on behalf of … huge donors like that,” Campbell said. “I’m unaware of any institution that has as deep a relationship with a donor as UCLA (has) with the Pom folks.”

Campbell said a difference between this situation and other potential conflicts of interest is that the Resnick Foundation is so tightly woven into the university fabric, beyond just research ties.

“The problem here is it’s the institution itself that’s essentially the organism … conflicted,” Campbell said. “It just depends on the extent to which the institution is willing to sell its reputation to objectivity and truth to a group of people who intend to sell it.”

Josephine Johnston, director of research at the Hastings Center, which studies bioethics, said one of the biggest problems that results from relationships like those between UCLA and Pom is that the university’s research reputation is cast in a questionable light, even if no conflicts of interest actually took place.

“Everything looks suspicious all of a sudden,” Johnston said. “Now the onus is on the university to say ‘no, it’s O.K.’”

In a memo outlining the UC’s policy on integrity in research, the UC is supposed to uphold “precautions against real or apparent conflict of interest.”

Johnston said such strong relationships between a university and its donors are risky because the relationship could actually have an effect on judgment and even if there was no impact, it makes the research, university and researchers all look untrustworthy.

“Trust is hard to win back. … (These relationships) raise a question and that’s a very hard thing to overcome,” Johnston said. “It creates the impression that Pom Wonderful has a lot of sway over the institution and the researchers, even if it’s not true, and that’s damaging to UCLA.”

Emails obtained by the Daily Bruin between several doctors at UCLA Health and officials in the clinical development department at Pom show continuing communications between the two entities, including intentions to talk on the phone or meet in person more than 20 times over the course of about a year.

“I need to know a little about how close this arrangement will allow me to be to the (sponsored) study,” states an email from former Pom employee Brad Gillespie to Dr. Gary Small, the director of the UCLA Center on Aging and founding director of the UCLA Memory Clinic. Small, also a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine, has conducted research studying the effects of pomegranates on the brain.

Rob Six, a spokesman for the Resnick’s Roll Global holding company, said in an email statement that there are a number of reasons for ongoing communications between Roll Global and researchers, including satisfying logistical needs of the studies.

“The reasons for such contacts appropriately vary depending on the individual circumstances of a given experiment or study,” Six said in the email. “Pom does not, however, micromanage researchers in the conduct of a study. Instead, the researchers are solely responsible for the conduct of any given study and their decision-making during the course of a study and analysis of study outcomes are absolutely independent from their study sponsors.”

UCLA Health spokespeople said in an email statement that contractually sponsored research generally allows the “sharing of research results between UCLA researchers and industry representatives but does not provide for any preferential access.”

UCLA’s involvement with Pom is not the only situation to draw concerns from members of the community lately.

On Tuesday, the UC Board of Regents paid a $10 million settlement to the former chairman of UCLA’s orthopedic surgery department in a whistleblower lawsuit, after he alleged the school’s doctors took lucrative payments from medical companies and subsequently compromised patient care.

The Los Angeles Times reported that two years ago, then-UCLA surgeon and orthopedic surgery chairman Robert Pedowitz sued UCLA, the regents, university officials and other surgeons, claiming they retaliated against him after he accused university doctors of conflicts of interest in their research and treatment of patients.

Campbell said other large universities nationwide have wrestled with the same sorts of issues, and some employ methods of oversight to ensure conflicts of interest don’t take place. He added that the relationship specifically between UCLA and the Resnicks, however, is unprecedented to his knowledge.

UCLA Health’s conflict of interest policy requires that all university employees and officers “disqualify themselves from making, participating in making, or attempting to influence any decision of the university where the individual has more than a nominal personal financial interest in the decision.”

UCLA Health spokespeople said in an email that no concerns about conflicts of interest about the Pom-sponsored research have been raised in their Conflict of Interest Review Committee or Office of Compliance.

The policy goes on to provide specifics about relationships with vendors and other aspects, but “does not provide … specific guidance on the conflict of interest situations that are unique to the biomedical environment,” because each case is reviewed individually.

Feinberg and three other officials approved the policy.

Between 2010 and 2013, Feinberg received more than $100,000 from the Resnicks for the position of consultant/advisor, according to Feinberg’s 700 forms, which provide public disclosure of economic interests to the state.

UCLA Health said via email that Feinberg did receive pre-approval to serve on Roll Global’s scientific advisory board, which is required under university policy.

“We understand our obligation to maintain the public’s trust, regularly review our policies and procedures, and are always open to ways to enhance and improve how we carry out our missions to educate and improve society,” UCLA Health representatives said in the email.

Six said in an email that Feinberg is not a consultant for Pom specifically, but that his primary role is to provide strategic advice on Roll Global’s Aspect Imaging business, which designs and manufactures MRI systems.

Six added that Feinberg has attended some meetings regarding Pom research “to provide a patient provider and health promotion perspective.”

Responding to the criticism

The information about Feinberg’s relations with the Resnicks from the disclosure forms, however, provoked anger from some students at UCLA and around the country.

The United Students Against Sweatshops, a national student labor organization, started a petition last summer called “Tell UCLA’s David Feinberg: Universities Are Not for Sale.”

The petition claimed that Feinberg was supplementing his “already exorbitant salary from UC with six-figure payouts from corporate interests who are using university research for false advertising campaigns,” and asked fellow students to use a form to send an email message to Feinberg and the UC regents.

Dr. Louis Ignarro, a retired UCLA professor emeritus who conducted research on some molecular effects of pomegranates, said in an email he was a member of Pom’s scientific advisory board before deciding to conduct research on pomegranates, for which he later asked and received funding through the Resnicks.

Ignarro, a Nobel laureate, said the Resnicks did not contest his results or ask him to support any claims that they may have used later in advertising.

Ignarro’s research was published in 2005 and 2006, and was cited many times by Pom, including indirectly on its website where Pom states that its products “have been the subject of over 70 published scientific studies … conducted by leading researchers, including a Nobel laureate, who are affiliated with top universities across the globe.”

Ari Mackler, a Pom representative who was among those who regularly communicated with UCLA researchers according to emails, also edited an academic study released in 2013 that suggested some positive correlations between “pomegranate therapy” and certain health benefits like sensory-motor coordination.

Though the study mentions Pom Wonderful pomegranate juice in the research, the end of the paper states that “the authors have no conflicts of interest with any of the companies mentioned.”

Campbell said he understands it is difficult economically for universities like UCLA to turn down money when it is offered, but that the university could restrict Pom from specifically funding research on campus.

Six said current studies funded by the Resnicks at UCLA include an ongoing trial exploring the effect of pomegranate on bacteria in the body and studies examining the relationship between pomegranates and memory and cognition.

Even if UCLA wanted to continue to allow Pom to fund campus research, a third-party organization independent of ties could preside over it, to review the research and conclude there is no direct or indirect influence resulting from the Resnicks’ donations, Campbell said.

“If there is an institution that should be able to take the high road, I think UCLA should be among those institutions,” he said.

Aside from media relations representatives, no current UCLA or UCLA Health-affiliated employees responded to requests for comment.

From my experience, UCLA has no interest in promoting people’s health. They are all about the money. When they botched my surgery, they instantly began to cover up their mistakes, which left me in far worse health than if I had known that there were major complications. You can find out about my story and learn how to protect yourself from bad medical practices at http://UCLApatientcare.com.