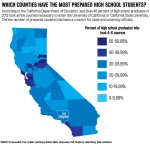

Less than 40 percent of last year’s California public high school graduates were qualified to attend California’s public universities, raising concerns among education experts and policy makers that the state will have an insufficient number of college-educated workers.

According to data recently released by the California Department of Education, about four in 10 public high school graduates in 2012 took the required A-G courses necessary to apply to the University of California. A-G courses are comprised of 15 classes, including mathematics, history, English, science and performing arts. Students must get at least a C in the required classes to be considered for admission to the University of California and California State University.

Despite the lack of eligible applicants in California, a growing number of students are applying for the UC and CSU. Last year, UCLA alone received more than 100,000 applications for freshman admission, the most out of any college in the U.S.

But large numbers of students from low-income and first-generation backgrounds do not apply because they are not eligible, said Stephen Handel, UC associate vice president of undergraduate admissions. He said this is why the UC especially tailors its outreach programs to disadvantaged groups.

Still, the academic gap is projected to cause a shortage of 1 million bachelor’s degrees in California by 2025 according to a report from the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonprofit research institution that aims to inform and improve the state’s policy.

“We will have jobs available but too few people will qualify to take those jobs,” said Audrey Dow, community affairs director of the Campaign for College Opportunity.

It is possible this number is low because many high schools’ curricula do not align with the courses necessary to be eligible for the UC or CSU. Dow said she thinks the low number of students qualifying for eligibility was because of the low number of students completing A-G courses.

“A lot of districts do not equate A-G courses with high school graduation requirements,” she said. “Too few students know that such a curriculum exists.”

Dow said she believes many high schools do not have A-G courses as their default curriculum because their main goal is to have their students graduate, not to send them to higher education.

She added that this makes it difficult for first-generation students who don’t know a lot about applying to college.

“With first-generation students, they don’t have family and peers who have had a college experience. They lack the strategies of more affluent families,” Handel said.

Reid Milburn, higher education and California budget consultant of the Michelson 20 Million Minds Foundation, a foundation that aims to make college more accessible through the use of technology, said another possible reason for the low number of students who are eligible for state universities could be what she calls the state’s lack of prioritization on education.

From 2008 to 2012, the state cut hundreds of millions from the UC. To make up for the cuts, the UC increased tuition by about $5,000 for resident undergraduate students during that period.

Milburn said the increased cost of tuition might have discouraged high school graduates from trying for the UC.

“Thinking about education is becoming a luxury,” Milburn said. “Trying to add school fees and cost of tuition becomes insurmountable for many students.”

To combat the problem, the UC Office of the President has workshops and counseling programs like Puente and the Early Academic Outreach Program aimed to prepare students for college. This year, UC President Janet Napolitano also sent letters to about 5,000 students from low-income backgrounds across California who had performed well on their PSAT exams, informing them about courses they need take to be eligible for the UC.

Programs like Puente and the Early Academic Outreach Program are targeted toward low-income and educationally disadvantaged youth. Many would be the first in their families to attend college.About 60 percent of students partaking in the Early Academic Outreach Program meet the UC eligibility each year.

“Many of the programs, like Puente, do wonderful jobs of bringing students. The problem is that they are not scaled,” Dow said. “They’re not serving the number of students that need to be served.”