Updated permits are not on display in several of the elevators across UCLA’s main campus, which could lead to thousands of dollars in fines for the university.

Permits are outdated or nonexistent in many of the buildings on UCLA’s main campus, including Ackerman Union, the Terasaki Life Sciences Building, Bunche Hall, Geology Building, UCLA School of Law and Haines Hall. Some buildings’ elevators had posted permits with expiration dates as far back as 2007.

There are more than 300 elevators on the UCLA campus, not counting elevators on the Hill or in UCLA-owned buildings in Westwood, said Erik Ulstrup, manager of electrical systems at UCLA.

Though current permits may not be physically posted, the university often has the permits on file in the Facilities Management Building, said Ulstrup, who is in charge of the maintenance and upkeep of UCLA elevators.

According to Subchapter 6 of the Division of Occupational Safety and Health’s Title 8 regulations, which governs elevator safety orders, “no elevator shall be operated without a valid, current permit issued by the Division.”

The regulations go on to specify “the permit, or a copy thereof, to operate a passenger elevator, freight elevator or incline elevator shall be posted conspicuously and securely in the elevator car.” Elevator permits generally last for one year.

Peter Melton, a spokesman for the Department of Industrial Relations, said a $1,000 fine per elevator can be levied on building owners who don’t have up-to-date permits posted, regardless of whether they have the permits on file.

Ulstrup said that although the permits should be posted, the failure to post them is not a sign of danger to the people using the elevators. He added that if the building owner and the elevator inspectors agree on a future inspection period, the permits are still generally valid regardless of the expiration date.

Permits in the Botany Building, Moore Hall, Fowler Museum and Young Research Library, among others, were expired.

Ulstrup said there are elevators with expired permits largely because he usually waits to contact the elevator inspectors until a year after the completion of the last inspection. He said he plans to contact the elevator inspectors in the upcoming year.

The small number of qualified inspectors relative to the number of elevators needing inspection leads to long periods between inspections as well as expired permits, Melton said.

“An expired permit is not evidence that an elevator is unsafe,” Melton said. “We like to compare it to license plate tags on your car: Just because they’re expired, doesn’t mean the car doesn’t run.”

UCLA’s last inspections took place from September 2012 to January 2013, when a single inspector was escorted around and individually checked the more than 300 elevators on campus.

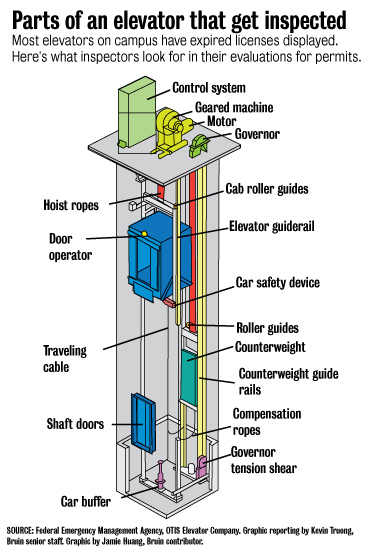

“The inspections are mainly for the safety of the elevator mechanics,” Ulstrup said. “It’s also the riding public too, there’s no doubt about that, but it is a lot to do with the safety of the people working on the elevators.”

Nile Bates, a third-year gender studies student, said she was trapped in one of the elevators in Ackerman Union for almost an hour on Oct. 31.

After pressing the alarm button in the elevator car without any results, Bates said it took two calls to the operator to get released.

“The experience made me nervous to take elevators again, especially since it took so long for me to get out,” Bates said. “Now I take the stairs a lot more.”

The inspection permit on file in the Facilities Building for Ackerman Union expired on Nov. 7.

Posting permits takes around 30 minutes per elevator, so installing them is a major investment of time and labor, Ulstrup said.

While he hasn’t heard of the process taking that much time, Melton said he knows installation requires special tools.

After the issue of the expired permits was brought to his attention, Ulstrup said he is working toward making sure all the up-to-date permits are being posted.

“We’re in the process and we’re getting there,” Ulstrup said.