Even prison guards who kept watch over jailed civil rights activists in Savannah, Ga., listened to the radio broadcast of the March on Washington.

After he was arrested during a civil rights demonstration, Rick Tuttle listened to the sounds of the cheering crowds that burst from the prison guards’ radio and reached his prison cell bars.

“The next few days, I could feel a shift in their attitude, partly because they were impressed by (the march), and also for another reason – that we might win,” said Tuttle, now a UCLA lecturer in public policy.

‘The touchstone for generations’

The March on Washington was organized nine years after the Supreme Court decision on Brown v. Board of Education officially desegregated schools. But one only had to drive just below Washington, D.C., to Virginia to find “Whites Only” signs in buildings, said Daniel Mitchell, a professor emeritus at the Anderson School of Management who went to the march on his day off of work.

The day of the march began with tense uncertainty, said Gary Orfield, director of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, who went to the march. National Guard troops lined the streets and the government shut itself down, afraid the demonstration would be violent, Orfield said.

Aside from the marchers and National Guard soldiers watching the streets, the city seemed deserted, he said. Later, however, it became clear that no violence would be involved.

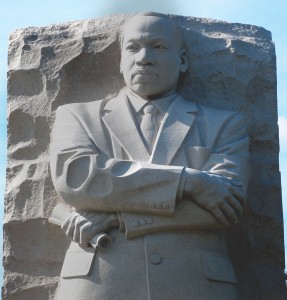

The march became famous in newspapers and history books for Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which he gave that day from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

But those who were at the march said it was difficult to even see the speakers because it was so crowded and the speaker lectern was so far away, said Mitchell, who did not watch King’s speech.

The real legacy of the day, Mitchell said, was the mere logistical accomplishment of getting so many people on the National Mall for a demonstration that was free of violence.

They weren’t there necessarily to accomplish a specific agenda, but rather to show a huge presence on Washington’s front lawn, Mitchell said.

“The march isn’t what actually changed the country, but it was a chance for people to come together and see that they were part of a big movement,” Orfield said.

‘A lifetime struggle’

After the march, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited major forms of discrimination, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 eliminated voting tests and other restrictions in the South while mandating federal oversight of Southern states’ voting policies.

Civil rights activism was relatively quiet at UCLA in 1962 and 1963, but the March on Washington and Birmingham demonstrations helped to change that, Tuttle said.

The winter following the march, UCLA students helped form a committee involving hundreds of volunteers to register black voters and send telegrams and letters to congressmen for the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, said Tuttle, who was a UCLA graduate student in history at the time.

But 50 years after the march, many Americans think the U.S. still has not made sufficient progress in civil rights equality, according to a recent study by the Pew Research Center.

Part of the difficulty of reaching complete equality is that the issues are less clear today than they were 50 years ago, Orfield said.

“There were some easier enemies (50 years ago). We had a whole system … in 17 states that was unambiguous and clearly evil,” Orfield said. “Right now we have much more complicated systems of inequality, and people have been calling them normal.”

Orfield pointed to the Supreme Court’s recent 5-4 decision to strike down a key part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, allowing nine states – mostly in the South – to change their voting laws without federal approval.

While justices who supported the decision said that the current times no longer necessitate such an “extraordinary” measure, justices who voted against the decision said the law had prevented policies that had more subtle forms of discrimination.

Paul Von Blum, a UCLA communication studies lecturer who drove for three days to get to the March on Washington, pointed to the small percentage of black students at higher education institutions in relation to other minority groups as an example of modern inequality.

Von Blum and Orfield said there are still just as many civil rights issues that need to be addressed as there were 50 years ago.

They added that they are discouraged they don’t see as many college-age individuals engaged in activism like they had been half a century ago.

“You have to look beyond yourself,” Von Blum said. “I know a lot more people who are only concerned with finishing school, getting a job and making money … Money is not enough.”

Meanwhile, Tuttle, Von Blum and Orfield have kept on with their activism through politics or, in Von Blum’s writing a book.

“I realized as a very young person that this struggle was a lifetime struggle,” Von Blum said. “It was not something that you drive across the country and do for a demonstration. You do this for your entire lifetime.”

There’s a reason my dad, Rick Tuttle wasn’t at the March on Washington: He was in jail for being a Freedom Rider.