American artist and furniture maker Richard Artschwager wanted to make something useless, so he created a sculpture.

“He didn’t mean ‘useless’ as in having no meaning or significance, but rather as in not having a practical function,” said Anne Ellegood, senior curator at the UCLA Hammer Museum.

Inspired by a scene from a cartoon, Artschwager nailed a stack of plywood boards together to make his sculpture, titled “Portrait Zero.”

The work is one of more than 145 of Artschwager’s pieces on display in the Hammer Museum’s new exhibition “Richard Artschwager!” until Sept. 1. The retrospective exhibition, which was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Yale University Art Gallery, features paintings, sculptures and drawings spanning more than six decades of the late artist’s life.

Critics, curators and art historians often grouped Artschwager, a contemporary of artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, into the pop, minimalism and conceptual art movements of the ’60s and ’70s.

Artschwager, however, is best known for an independent, dynamic artistic style and the unconventional mediums he applied in his works.

“He was extraordinarily difficult to categorize (and) talk about in some ways,” Ellegood said. “And every time people thought they figured him out … he would do something totally different, up (until) his death.”

Artschwager created work in artistic phases, relying mostly on a black, white and grey palette in his works in the ’60s and ’70s before introducing bright yellows, greens and blues in the past few decades.

Jennifer Gross, curator of the exhibition and the Seymour H. Knox Jr. Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Yale University Art Gallery, said Artschwager constantly experimented with the relationship between his works and viewers’ perceptions and interactions with them.

“His goal was really to make the viewer aware of how much we take for granted in the world around us,” Gross said.

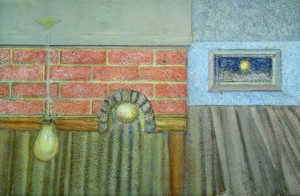

Artschwager often drew on his experiences as a furniture maker and baby photographer in his works, using items of furniture and photographs as subjects. Gross said he would, however, create a disrupted version of these familiar forms.

For example, “Description of Table,” one of the displays in the exhibition, is a cube sculpture of a table. The work was decorated to look like a table and tablecloth with panels of melamine laminate, a plastic material that was manufactured with different patterns ranging from blue marble to wood grain prints.

“(He) would basically stop the viewer in their tracks,” Gross said. “They’d have to work a little harder to look at the images he made.”

Artschwager also opted for textured materials like Celotex, a rough insulation material, in lieu of traditional canvases, as well as bristles and rubberized horsehair, all of which are incorporated into the selection of works on display. Ellegood said he chose these unusual materials to get viewers to pay attention to details in his pieces.

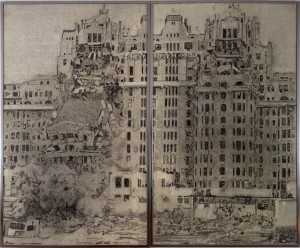

He based his mostly black-and-white paintings of luxurious homes, babies and demolished buildings on photographs he found in magazines or took himself. The textured Celotex, which was manufactured in different patterns like brushstrokes and rosettes, disrupted the image and his miniscule brushstrokes, making the compositions blurry and stuttered when seen up close.

Artschwager’s desire for unique textures also extended into his sculptures like “Exclamation Point (Chartreuse),” a life-sized exclamation point covered with fluorescent yellow bristles, Ellegood said. The thick bristles create shadows and distortions in the viewer’s perception of the piece, reiterating Artschwager’s interest in disrupting his compositions.

This work drew UCLA alumna Maria Andrea Cruz to the exhibition. Cruz, who received her bachelor’s degree in art history, said she had never heard of Artschwager before but was intrigued by a photo she had seen in the Hammer’s catalog.

Cruz said she hopes the Hammer’s displays of recent works like “Exclamation Point (Chartreuse),” which was created in 2008, will make contemporary art and artists like Artschwager more accessible to a younger generation.

“I hope people see that artists are still creating and (the art world) is not just this elitist kind of society,” Cruz said. “Contemporary art is important because these (artists) are everyday people, and their art is a self-expression of what we’re living through right now or in the recent past. That’s going to be a part of history.”

“I think (Artschwager) was not someone who would want to look in any traditional way at the world or operate within a system,” Gross said. “He had a very unique perception of the world, and his own curiosity and perception motivated him.”