This article was updated on May 28 at 5:40 p.m.

A picture of Lloyd Shapley has hung in the outdoor lobby of Bunche Hall since he won the Nobel Prize this past fall.

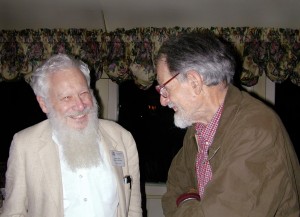

Peering out from under the grandiose caption “Master of the Game,” Shapley is the visage of a pensive genius: bushy hair sticking out from the sides of his balding head, a white beard and blue eyes that convey a glint of brilliance despite having sunken with age.

This appearance of genius is not deceptive. Shapley is regarded as a guru in the field of game theory, for which he won last year’s Nobel Prize in economics.

Shapley taught the undergraduate economics course in game theory at UCLA in the mid-1990s.

Having the man who would one day win the world’s highest honor in economics teaching an undergraduate course in game theory is like having Stephen Hawking teach a college course in astrophysics.

One year before Baucells enrolled in Shapley’s undergraduate economics lecture as a graduate student, the 1994 Nobel Prize for Economics had gone to John Nash, Shapley’s contemporary and also a noted game theorist. Baucells recalled mumblings about Nash’s prize being a slight to Shapley.

“The talk at the time was that Shapley was very upset because he didn’t get the Nobel Prize and Nash did,” Baucells said. “I haven’t heard him say that.”

Nonetheless, there is something of a consensus among game theorists that Shapley’s prize is years overdue.

“Shapley has done more than all the previous game theory Nobelists, even when taken together,” wrote Robert Aumann, himself a Nobel-winning game theorist, in a statement on the UCLA economics department website. “I am not exaggerating.”

Though he retired over a decade ago, Shapley holds offices as an emeritus professor in both Bunche Hall and Mathematical Sciences. As an undergraduate student in mathematics/economics, it will be many long years before I start working on material as complex as the problems Shapley studied, if it happens at all. Nonetheless, Shapley’s gold-gilded career stands as an inspiration for students like myself at the institution where he spent more than two decades researching and writing about game theory.

Shapley’s age puts him in the same generation as many legendary game theorists. After awarding Nobel Prizes to many of his contemporaries and collaboraters, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm, Sweden finally honored Shapley himself, as well as Harvard economist Alvin Roth.

***

After finishing up his Harvard undergraduate degree in mathematics, Shapley arrived at Princeton in 1949, setting foot in a tranquil New England hamlet in the midst of a mathematical revolution.

Albert Einstein famously wandered the tree-lined avenues of the college town, sockless, past overgrown Gothic facades and quaint colonial houses. Einstein, who at the time busied himself by lobbing mathematical grenades into the edifice of quantum physics, described the town as “a quaint and ceremonious village of puny demigods.”

Luckily for Shapley, at the time he enrolled as a graduate student in mathematics at Princeton, two European mathematicians – both professors there – had just published “The Theory of Games and Economics Behavior,” a seminal work for game theory.

Perhaps because of the celebrity that work earned, game theory began to take a hold at Princeton. A small group of students, including John Nash and David Gale, who would work with Shapley on the 1962 paper largely considered to have won him the Prize, took a deep interest in the subject.

By the time Shapley arrived at Princeton, he had already demonstrated a unique mathematical aptitude. In a Nobel interview, he recalled beating his father, renowned astronomer Harlow Shapley, at a complex card game called “Hell’s Bells,” involving various values and formulae.

In the 1950s, he was honored with a combat medal for his work as a codebreaker in the Pacific Theater of World War II.

As a graduate student, Shapley had already assumed the countenance of a prolific intellectual. Sylvia Nasar, who wrote a biography on Nash, paints a picture of Shapley that could have been the character description of a quirky genius in a B-list screenplay:

“Tall, dark and so thin that his clothing hung from him like a scarecrow’s, Shapley reminded one woman of a giant insect; another contemporary says he looked like a horse. His normally gentle demeanor and ironic banter hid a violent temper and a harshly self-critical streak. When challenged in some unexpected fashion he could become hysterical, literally vibrating and shaking with fear.”

Gangly and ill-tempered, Shapley seems to have been typecast for the role he would play: the intellectual forefather of a generation of economists, mathematicians and political scientists.

***

Long before they would win the Nobel Prize together, Alvin Roth visited Shapley as a student would visit an old master. Shapley was working at the RAND Corporation, a think tank with an illustrious history in game theory, just blocks from the Santa Monica pier. Starstruck by the opportunity to meet the famous scholar, Roth made the trip to Santa Monica to solicit Shapley’s input on the dissertation he had just published. Roth recalled being surprised to hear the RAND security guard address Shapley on a first-name basis.

“I was a new game theorist, and Shapley was one of the gurus, one of a small number of gurus,” said Roth, describing Shapley as a “terribly forbidding figure.”

The meeting ended with Shapley hopping in his station wagon and shuttling the man with whom he would one day win the Nobel Prize back to the airport.

Only a few years later, Shapley made the move just a few miles down Wilshire to UCLA, where he took a dual professorship in mathematics and economics. From accounts of those who worked with him here, Shapley was no less the quirky genius at UCLA than he had been at Princeton.

Baucells recalled that Shapley kept an irregular sleeping schedule, working late into the night, a fact also noted in Nasar’s account of Shapley’s Princeton years.

Dov Monderer, a visiting scholar in the 1980s who collaborated with Shapley, wrote in an email that Shapley rarely attended departmental meetings at UCLA if they were scheduled before noon – even if the meeting was important to Shapley himself. Monderer chose to communicate with me via e-mail because of a recent surgery inhibiting his speech.

At game theory conferences, Shapley would organize tournaments of “kriegspiel,” a variant of chess where the opponents do not see each other’s pieces. By Monderer’s account, Shapley played this game with great skill – a feature one imagines made use of his brilliant mathematical mind. But despite the incredible precision and complexity of thought he no doubt possessed, conversations with Shapley could meander from subject to subject.

“If you wanted to talk about something, you had to continuously bring him back to the topic,” Baucells said.

***

The paper that eventually won Shapley his Nobel was peppered with terms and examples that hardly seem appropriate for a field dominated by mathematical models and polysyllabic paper titles.

The Prize-winning concept of “stable allocations” originates from a paper Shapley co-authored at RAND rather lightheartedly titled “College Admissions and the Stability of Marriage.” In his Nobel lecture, Shapley described the idea using a game he called “Get a Date,” involving the behavior of a certain number of women and a certain number of men in a sort of marriage market.

Imagine a “market” for men and women seeking relationships with one another. Call that market UCLA. Assume, for simplicity, that UCLA’s population of almost 30,000 consisted of exactly half men and half women.

In a market like this, Shapley and Gale proved the important point that a stable distribution of pairs exists where no man and woman stand to gain by abandoning their current partners for one another. The idea seems trivial in the language of the birds and the bees, but the same tenets apply equally well in more serious markets. The market which matches students to schools, for example, obeys similar principles.

“There wouldn’t be any blocking pairs,” Roth said. “There wouldn’t be any instabilities of a student and a college who both regretted that they hadn’t matched up.”

From that axiom, Shapley and Gale were able to extrapolate a set of algorithms that organize a market in equilibrium, or a “stable allocation.”

Roth’s profession is “market design,” and he runs a blog of that name. In that field, which won him the Nobel Prize alongside Shapley, he has applied the principle of stable allocation in a multitude of practical arenas, matching organs to donors, high school students to campuses and medical residents to hospitals.

Unlike Roth, Shapley was a mathematician, working on more abstract game theory that works just as well with 10 or 20 players as with n players or an infinite number of players. He admitted in an Associated Press interview to never having taken an economics course in his life. But nonetheless, his musings about how colleges interact with students and women interact with men find applications across various fields of empirical research.

“Game theory is the set of tools by which we interact with each other,” Roth said. “You could throw a baseball without knowing calculus, … and you could interact with people without knowing game theory. But when you want to talk about those things in a scientific way, you need some tools, and calculus and game theory are those tools.”

***

To my dismay, I will never get to meet Lloyd Shapley in person. However, a series of anecdotes and descriptions form a piecemeal picture that is every bit as brilliant as his idiosyncrasies make him seem. From his bizarre sleep schedule to his penchant for complex analytical games, he fits almost entirely the archetype of a mathematical superstar.

The average undergraduate student of game theory is likely to learn about concepts like the Nash equilibrium. But a student is much less likely to have heard the personal narrative of John Nash, the Princeton scholar who illustrated the concept before lapsing into decades of schizophrenic delusions.

Even less well-known than Nash, whose story has reached some level of fame in a prize-winning biopic starring Russell Crowe, is Shapley, his contemporary and one-time mentor. While students can easily understand game theory concepts without knowing these characters, the stories of a handful of scholars who popularized the outlandish field are surprisingly illustrative of game theory itself.

To have been the setting for Shapley’s story over the space of twenty years is a credit to UCLA and its graduates. UCLA’s narrative is inextricably tied up with the man who preferred to play chess against an invisible opponent.