Since the 1980s, undergraduate female students have outnumbered their male counterparts on college campuses, a fact education officials have touted as an indicator that America’s higher education system is moving toward an environment in which men and women have equal opportunities to succeed.

There is now such a gap between the number of men and women attaining undergraduate degrees that some observers are concerned men are falling behind.

Yet women publish far fewer academic papers across the board relative to their male counterparts and remain underrepresented in certain fields. Gender equality in higher education is more complicated than enrollment statistics imply.

These problems are systemic, including a faculty gender gap in many departments and a continually lagging number of female students who attain advanced graduate degrees in male-heavy areas of study. In most cases, the imbalance is not the result of any intentional discrimination against women.

[media-credit name=”Elizabeth Case, Stephen Stewart” align=”aligncenter” width=”620″]

[media-credit name=”Elizabeth Case, Stephen Stewart” align=”aligncenter” width=”620″]

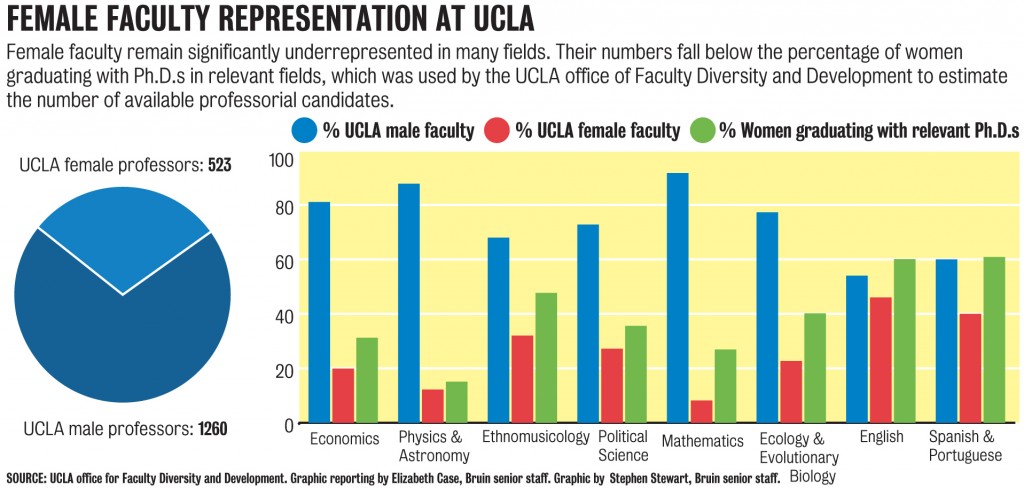

Still, women remain an undeniable minority in faculty in a wide variety of disciplines, from ethnomusicology to mathematics, as their numbers fall consistently under the amount of estimated “available” female professorial candidates. To combat impediments for women in academia, our university needs to ramp up support for women pursuing advanced degrees, particularly in those fields that are heavily male-dominated.

The Chronicle of Higher Education surveyed millions of academic papers and found that female faculty still lag behind their male counterparts in terms of having their research published, and academic subfields that do have a larger number of female researchers tend to be those that are consistent with gender roles, such as child development and feminist history.

For instance, from 1991-2010, women were authors of only 13.9 percent of scholarly works on economics, 12.1 percent of works on philosophy and 10.7 percent of works in mathematics.

Even at a university like UCLA, where the administration prioritizes a diverse student body and faculty, women are still significantly underrepresented as faculty in departments as varied as political science and mathematics.

Dimitri Shlyakhtenko, chair of the mathematics department, said this has consistently been a problem in the mathematics community at large, despite some slow improvement. According to Shlyakhtenko, significantly fewer women go on to pursue higher degrees or publish research in mathematics.

Especially in mathematics and the physical sciences, societal expectations add pressures to women interested in an advanced degree.

Lauren Holzbauer, a graduate student in astrophysics, experienced this first hand. She said she was warned by a friend that attaining a doctorate would make it more difficult to find a husband. However, studies show this is not the case – according to the U.S. Census Bureau, women over the age of 25 who attain advanced degrees are no less likely to be married than their lesser-educated counterparts. However, studies show women are more likely to prioritize family over their careers, and men on the same track are more likely to have a spouse or caregiver to help with family responsibilities.

So while basing one’s educational plans on marriage prospects may no longer be a necessary concern, familial prospects might be. And social factors still influence a female student’s experience in graduate school. Though Holzbauer did not notice much of a drop-off in the proportion of women between her undergraduate and graduate courses, she has taken courses in which she was the only female in her entire class – a situation in which she said she felt she was perceived differently from her male classmates.

This kind of environment – one in which female students are inadvertently made to feel as outsiders by virtue of their small numbers – can play a role in discouraging more women from pursuing degrees in these fields, making it difficult to work toward a balance.

Though it is impossible for our university alone to shift cultural perceptions and societal biases against women, our administration can do more to make the academic environment friendlier for female graduate students and faculty.

Numerous studies suggest that female students are more likely to pursue degrees in fields typically populated by men if they find other females in the field to look up to.

Taking this into consideration, both the UCLA office for Faculty Diversity and Development and departments with especially skewed male-female ratios might consider founding or increasing mentorship opportunities specifically aimed at connecting women in the same field.

Such a program could include mentoring between female graduate students and faculty, as well as between female graduate students in their first few years of their program with those who have more experience navigating graduate school.

This is just one idea. Although UCLA has made strides to recruit more women faculty members and make attaining advanced degrees a more attractive option for women, a severe gender imbalance in certain fields persists and will not be fixed on its own. Without a concerted effort to significantly remedy the lack of female students and faculty in these academic disciplines, the cycle will continue.