Patients who lost their eyesight over the course of their lifetime can now be treated to partially restore their vision, after the Food and Drug Administration recently cleared an “artificial retina” device.

The device, called the Argus II Retinal Prosthesis System, is designed to help patients who have retinitis pigmentosa and patients who start losing their eyesight as they grow older, said Wentai Liu, a professor in the bioengineering department at UCLA who helped engineer the device.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a disease that damages the retina’s ability to detect light and causes a loss of eyesight.

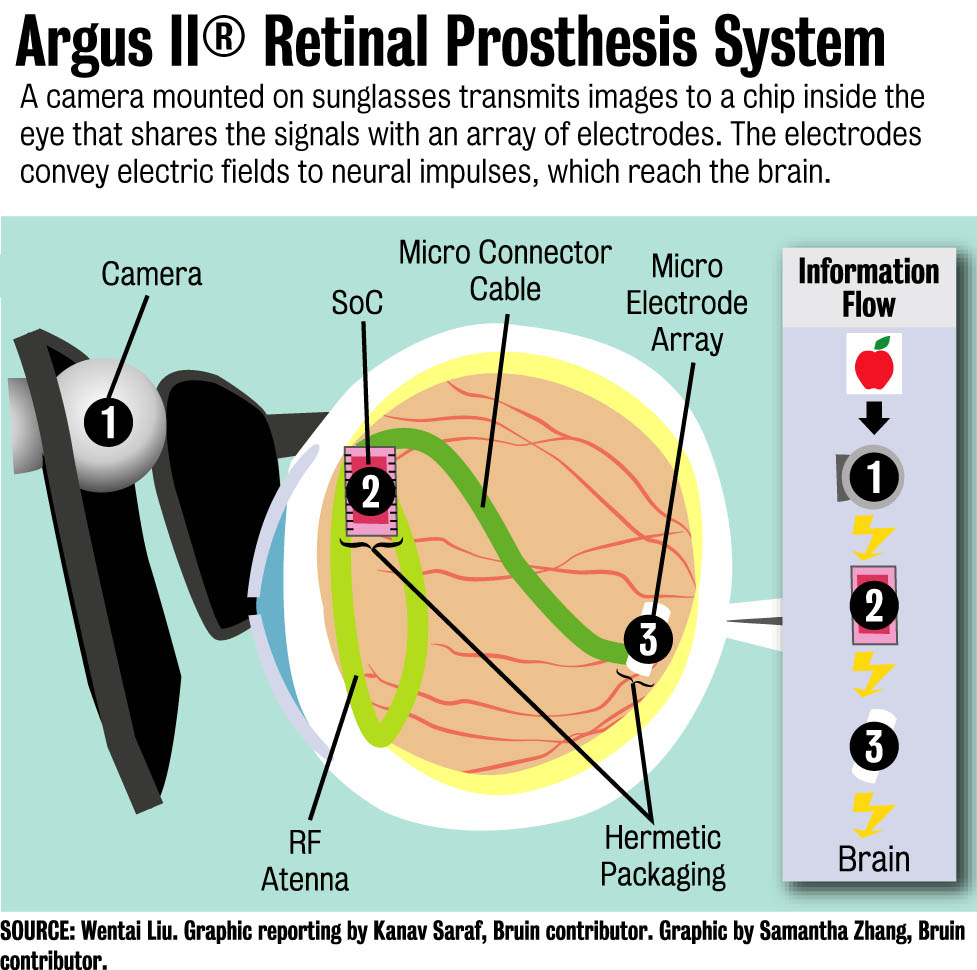

To restore eyesight using the artificial retina device, a camera is mounted on a high-tech pair of sunglasses to transmit images to a sheet of electrodes implanted inside a patient’s eye.

The device has been in the works for more than two decades. Liu started working on the device in 1988 when two neurosurgeons, Dr. Mark Humayun and Dr. Eugene de Juan Jr., currently professors at the University of Southern California, asked him to help design the retina implant.

[media-credit name=”Samantha Zhang” align=”alignnone” width=”977″]

[media-credit name=”Samantha Zhang” align=”alignnone” width=”977″]

At the time, Liu was not familiar with the biological aspects of the research. His focus had been on electrical and computer engineering.

“The neurosurgeons gave me a handbook on the retina to read, so I started from ignorance and educated myself,” Liu said.

Liu said he became a biologist “by training” to make the plan for an “artificial retina” a reality.

The research team’s strategy when developing the device was to bypass the damaged photo-sensation layer of the retina, a tissue that collects light inside the eye, and directly stimulate the other layers of neurons to help form images in the patient’s brain.

The first breakthrough for the artificial retina was in 1993, when the first experiment was conducted to see whether electrical simulations could induce light sensations.

During the experiment, surgeons put a single electrode in a patient’s eye, Liu said. After surgery, the patient was able to follow the movement of light emitted from a lamp.

For the last 20 years, Liu and his team have worked to improve the device, which now uses 60 electrodes to help create images in the patient’s brain.

Dr. James Weiland, an associate professor of ophthalmology and biomedical engineering at the University of Southern California, has been involved in studying the interface between the artificial retina device and the retina since 1997.

Weiland said that during clinical trials to confirm improved vision, patients are asked to locate a box on a touchscreen by viewing it through the device, or asked to read letters or words written on a board.

“(The patients) can’t do that without the device, but with the device they are able to achieve this very well,” he said.

The “artificial retina” device, however, does have some limitations, Weiland said.

The device’s resolution is well below normal vision, he said.

Still, Weiland said patients who have used the device are able to navigate while walking and even carry out sorting tasks, like doing laundry.

The recent approval of the device was a great achievement for the team, said Dr. Kuanfu Chen, a former postdoctoral fellow at UCLA who started working on the device under Liu when he was at the University of California Santa Cruz. Chen has been an active member of the team since 2006.

“We believe now more people can be helped by this device,” he said.

The researchers are currently working to create a retina implant that can support a higher resolution than the current one, to help patients recognize faces better, read well and gauge the direction of movement easily, Liu said.

“People with neural disorders need hope,” he said. “Engineers can play different roles in solving such societal problems to provide this hope to them.”